Making a Box for a Chinese Painting

Photos by Forrest Anderson; video by Forrest Anderson and Donna Rouviere Anderson; original paintings in the public domain.

When we lived in China, we lived on Beijing’s main Avenue of Eternal Peace just down the street from the Forbidden City which was the former palace of China’s emperors. Obsessed by Chinese history in general and the Forbidden City in particular, we visited the palace countless times. It was there that we began a long-lasting love affair with China’s most famous painting, Along the River During the Qingming Festival (Qingming Shang He Tu).

This long panoramic ink painting on silk, usually dated to between 1085-1145, has been called China’s Mona Lisa. In the same way that the Mona Lisa captures the spirit of the Mediterranean world in one image, the Qingming scroll depicts idealized Chinese culture and life. When we had an opportunity to buy a fine copy of it hand-painted by a skilled Beijing artist, we snapped it up. Since then, we have carefully hand-carried our copy with us around the world, keeping it stored through multiple moves.

This month, we finally built a display box for this beloved family treasure.

The box was built of maple and ash.

It has dovetail and mortis-and-tenon joints reinforced by walnut dowels. To help protect the scroll from acidity from the wood, the box has been sealed with several coats of a high-grade finish.

Chinese scroll paintings are susceptible to light damage as are other artworks. To keep the scroll from fading, the display box has been placed away from direct sunlight in a bedroom where the shades are drawn during the day. A different section of the scroll is unrolled every three months to prevent any one section from absorbing light over an extended period.

There are many copies and versions of the Qingming scroll in museums and private collections around the world, but the one at the Forbidden City is believed to be the original. The painting is thought to have been created during or shortly after the highly sophisticated Northern Song dynasty.

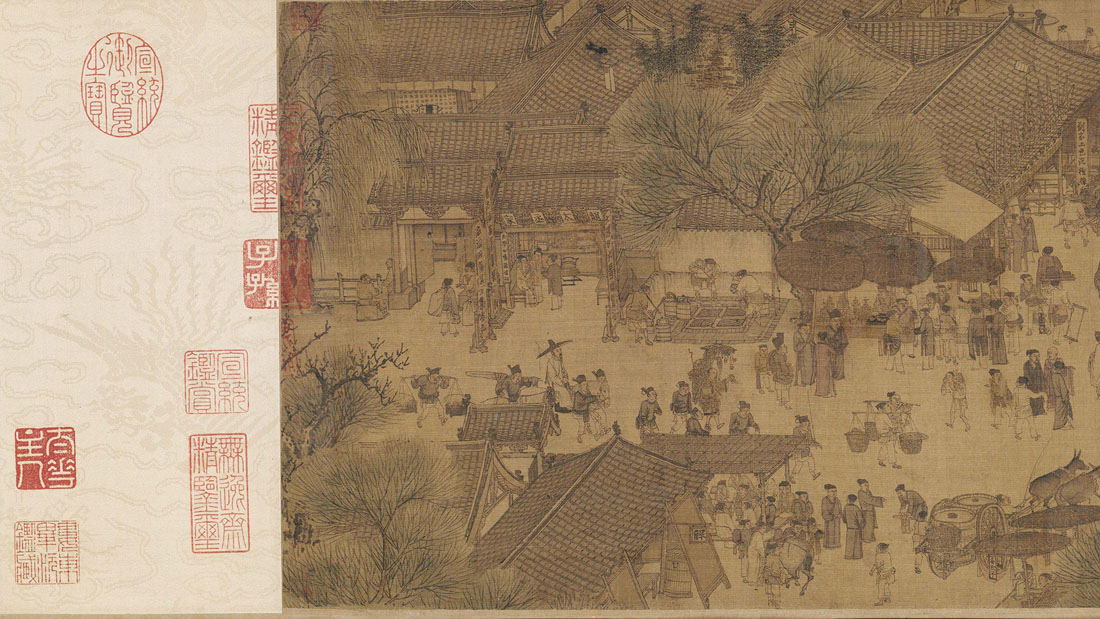

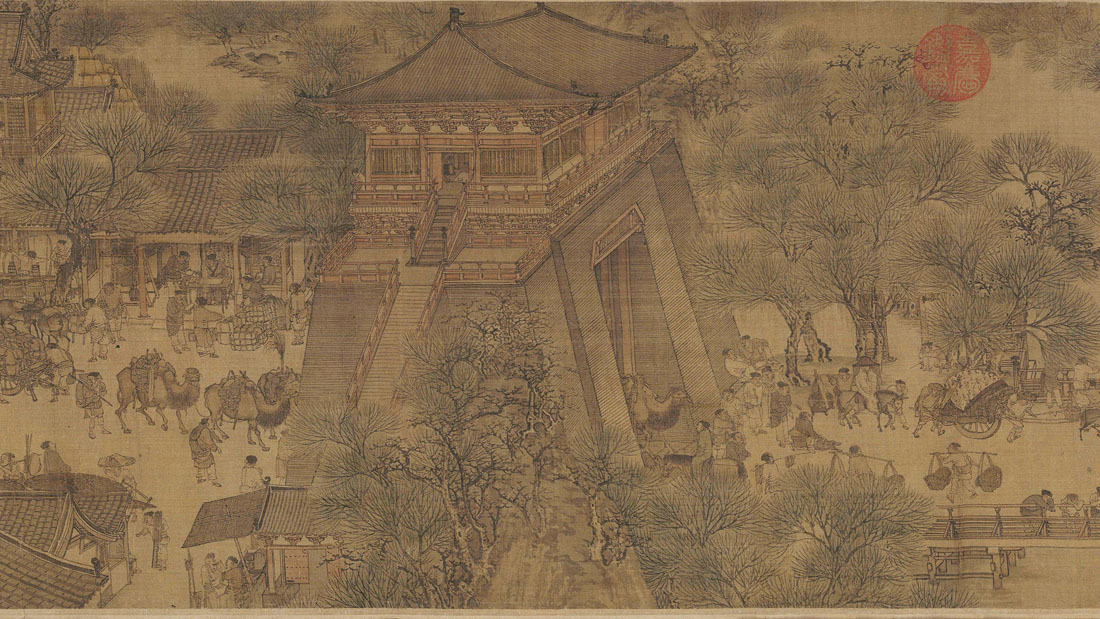

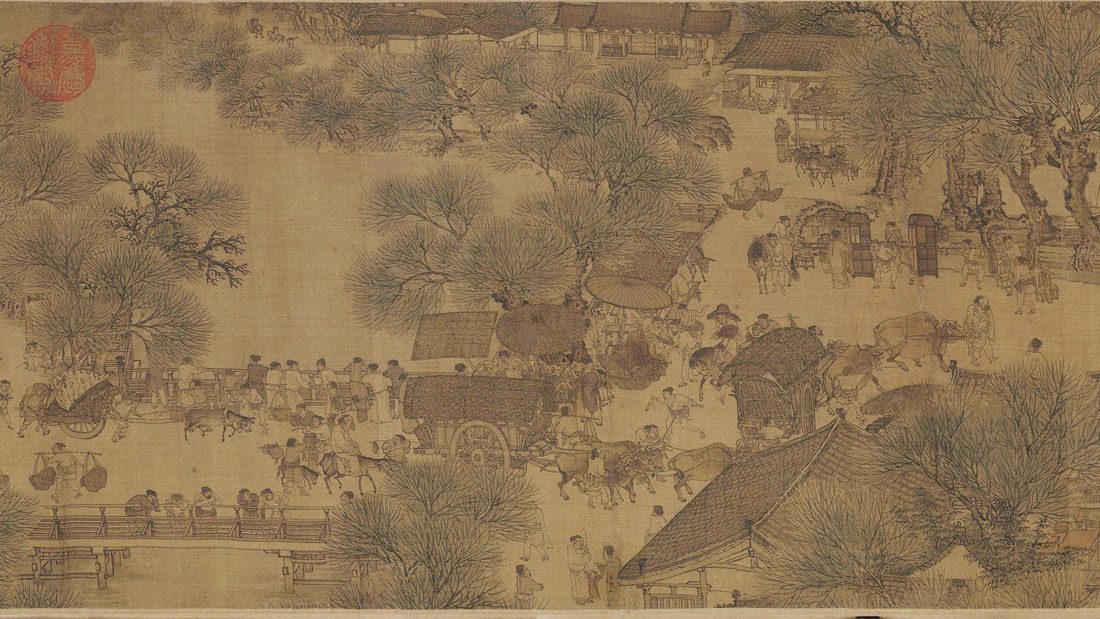

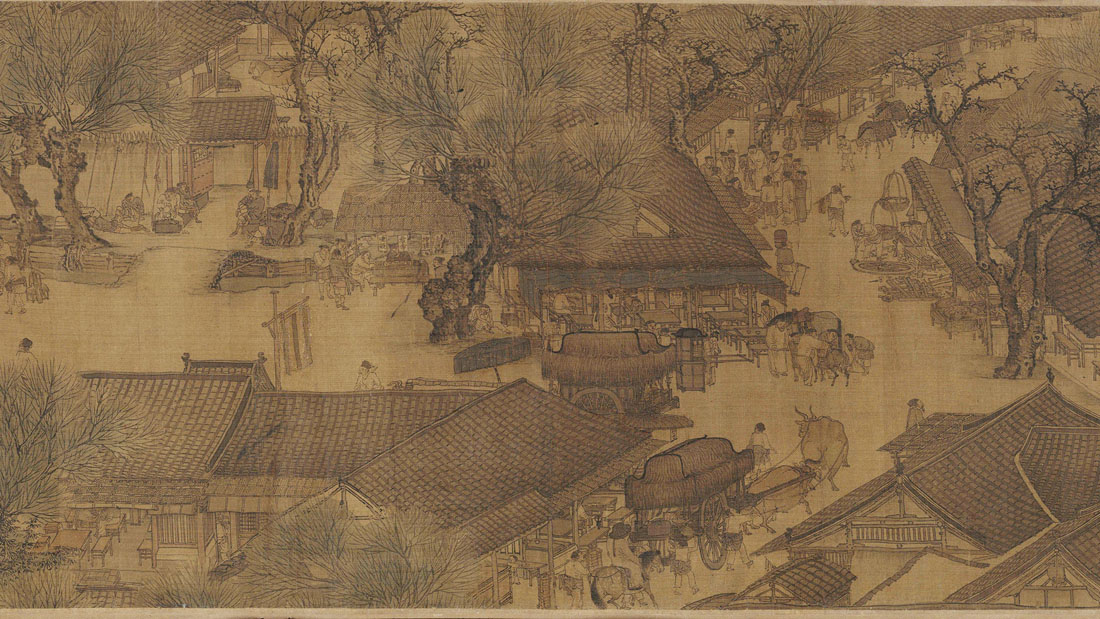

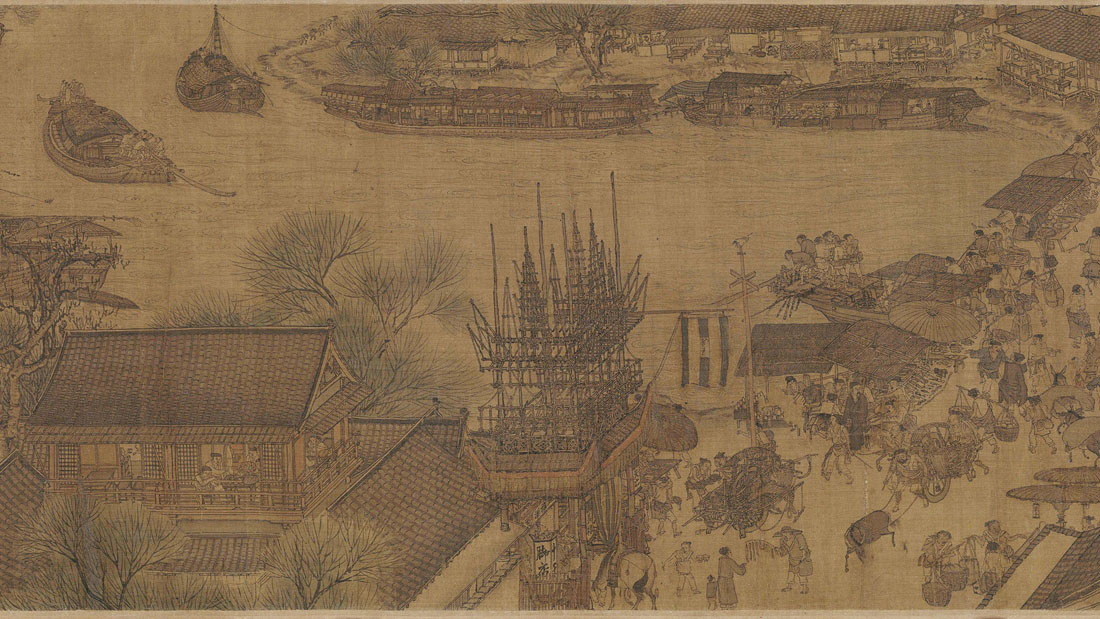

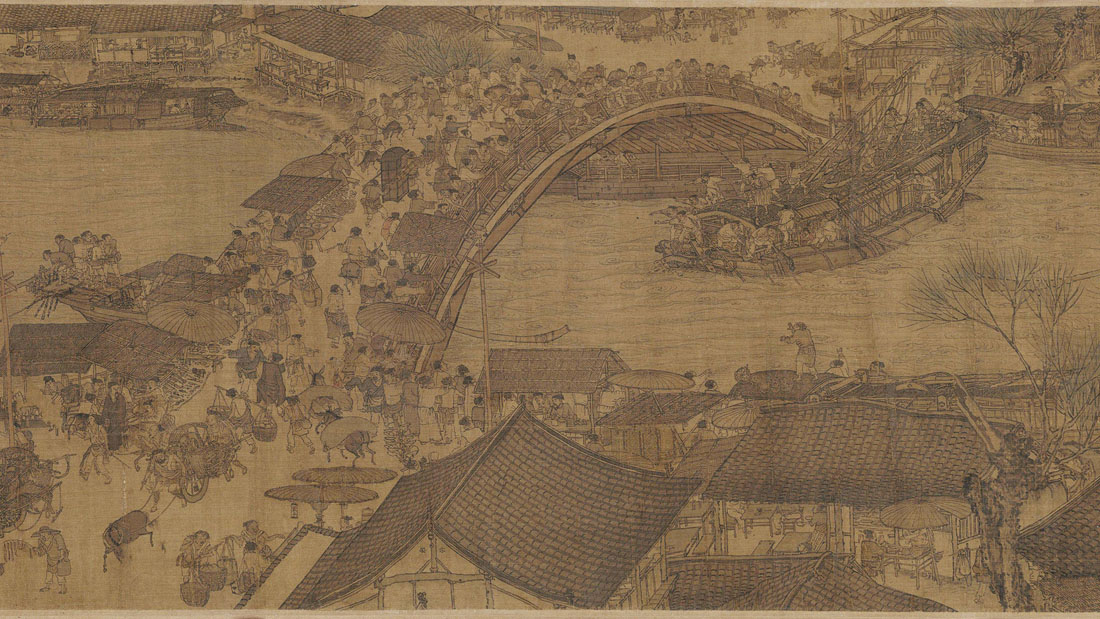

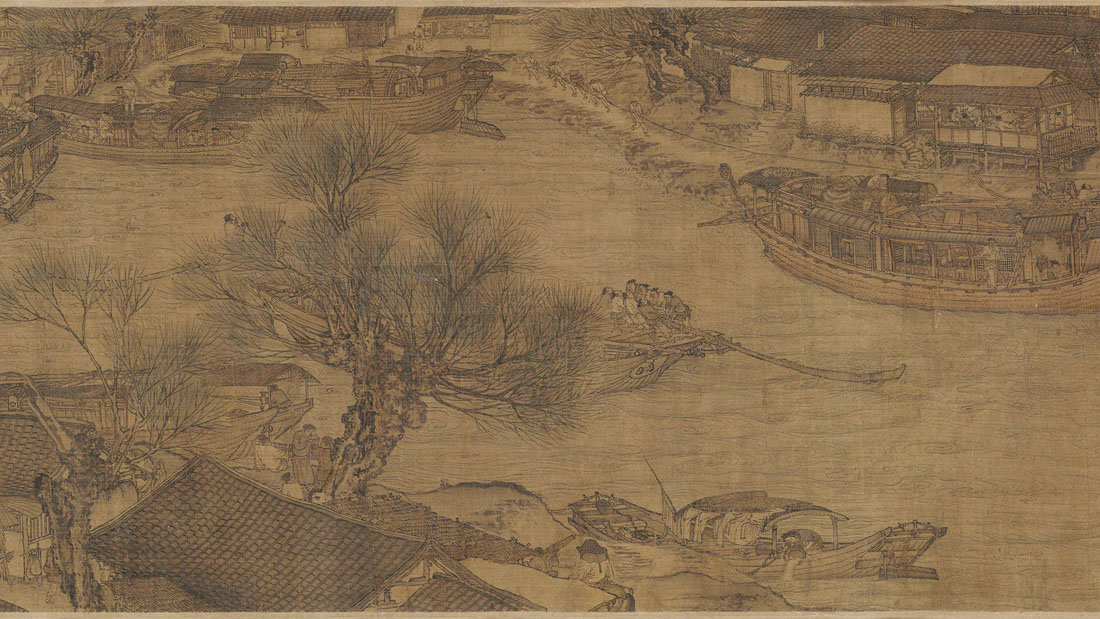

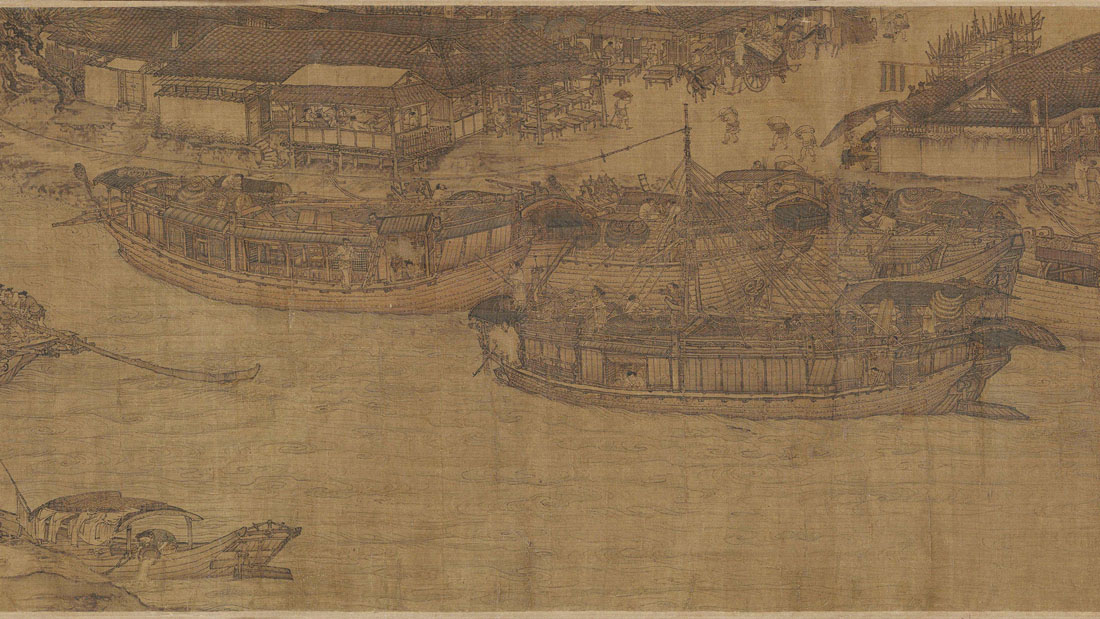

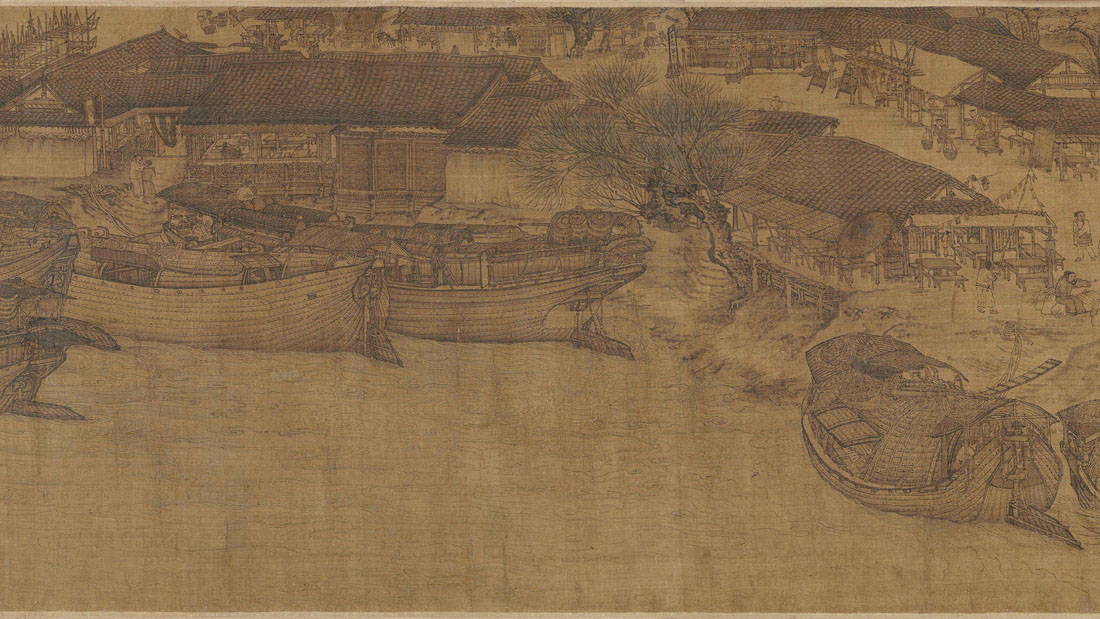

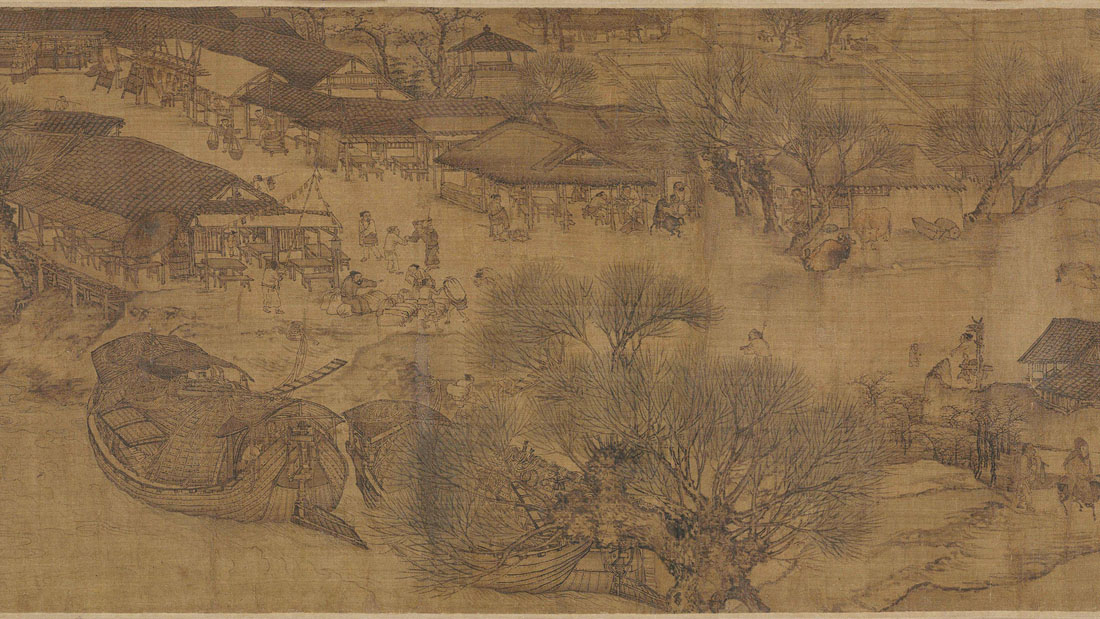

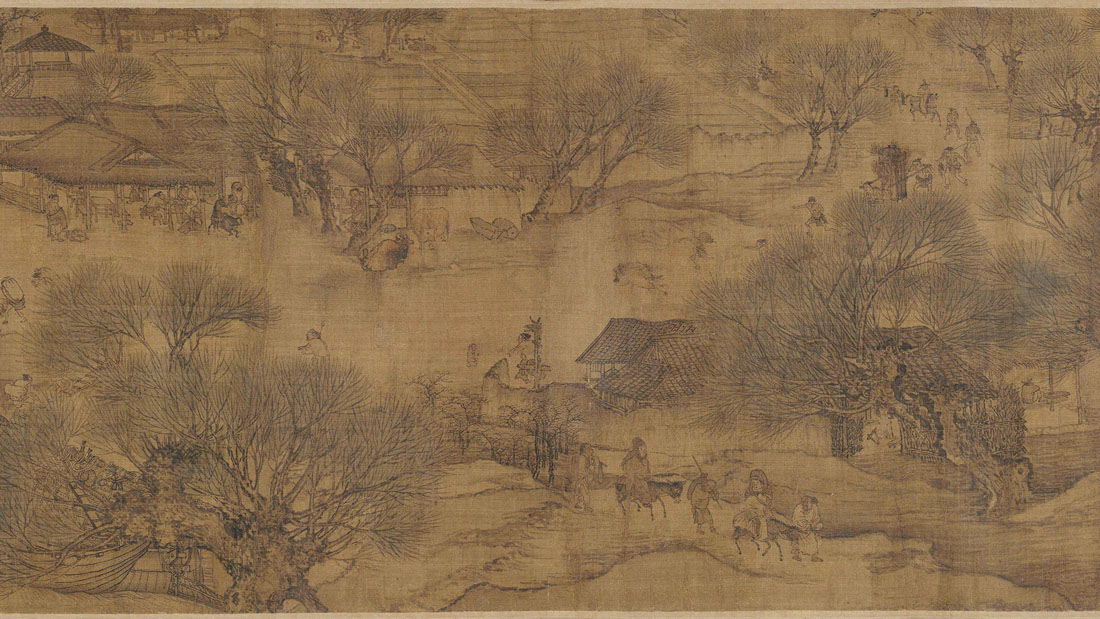

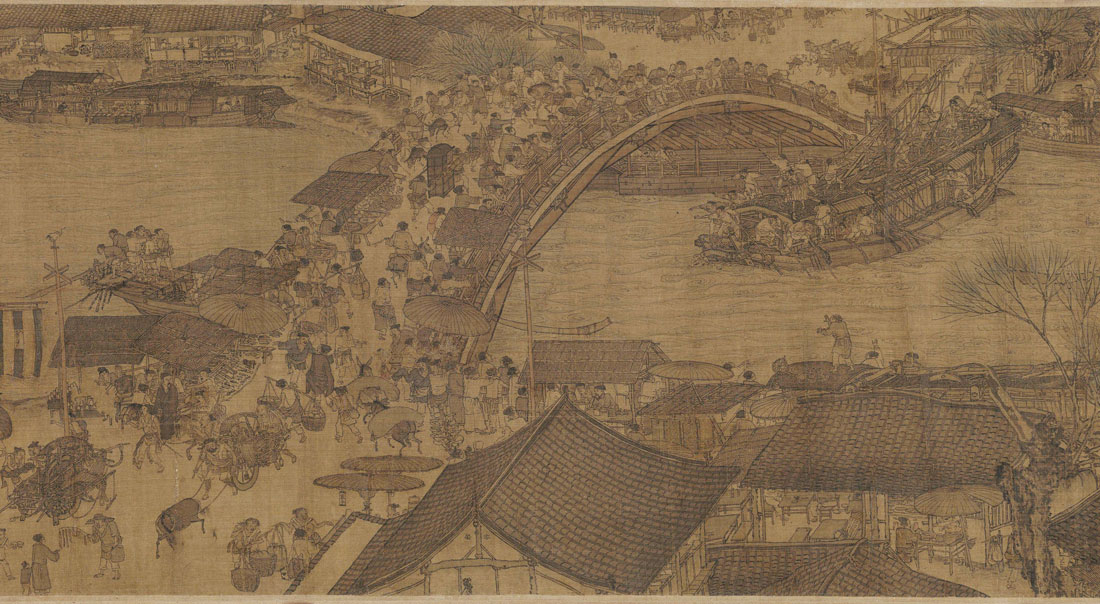

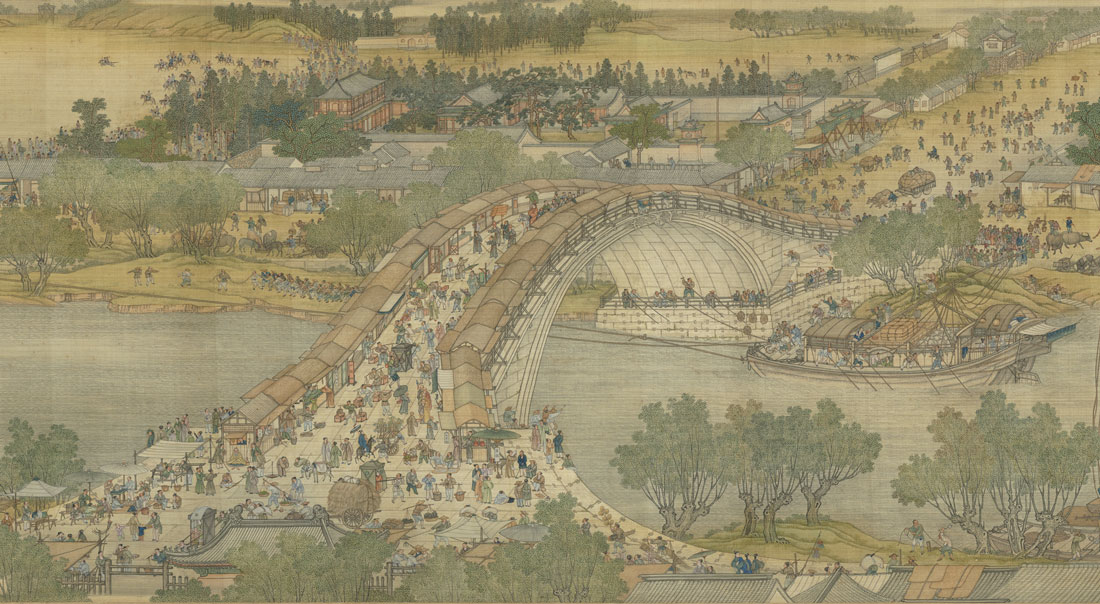

The scroll is 10.03 inches high and 5.74 yards long. It shows a scene along a river leading into a city along a major waterway. It unrolls on the right to show a tranquil rural scene with men and a string of donkeys in a rural setting. Rural houses are shown. As the scroll moves along, the countryside gives way to an urban scene. In the center of the scroll is a crowded rainbow bridge with vendors’ stalls. A cacophony of carts, peddlers, beggars, and others make their way over the bridge. Below is a commotion as a boat which has not lowered its mast is heading on the current toward the bridge. Frantic people are shouting and gesturing as the crew tries to steer the boat and lower the mast. Left of the bridge, the urban congestion grows as a city gate tower with a pavilion atop it comes into view. Camels move through the gate, shops of all kinds and vendors sell goods and the people from many walks of life congregate or pass through the gate. On the other side of the gate is a lively business district.

To scroll through the painting, click in the right area of the painting to advance the scroll or left to go back.

The painting has 814 human figures, 28 boats, 60 animals, 30 buildings, 20 vehicles, nine sedan chairs, 170 trees and landscape that ranks among the finest painting of the Song Dynasty.

Its enduring appeal lies in the artist’s capture of the essence of Chinese urban and rural society in its crowded vibrance and variety. For us, it is a much-loved image because it encapsulates much of China as it was when we first moved there. The scroll endlessly delights us in its ability to communicate across the centuries.

The scroll has a fascinating history, with mysteries as compelling as the mysterious smile that has long fascinated fans of the Mona Lisa.

1. The scroll’s name. Qingming means “clear-bright” but it also is the name of the early spring Chinese festival when people sweep their ancestors’ graves and of a day or “solar term” called Qingming that occurs roughly in April. The painting thus could simply depict a clear bright and peaceful day along the river, the festival or the day of the solar term. The second part of the title is not in question and means “going-along-the-river picture.” It refers to the river that runs the length of the scroll.

The scroll contains few clues that it is about the Qingming Festival in particular. Most people in it are going about their business, not celebrating a festival. A single sedan chair is decorated with weeping willows and other plants, suggesting it is the Qingming Festival, as households decorated with bundles of willow leaves and women placed willow twigs in their hair during the festival. The chair also is shown with a person carrying goods in baskets on a shoulder pole, and two people, one of whom is holding a shovel that may have been intended to be used to clean graves. However, this chair is the only one of several sedan chairs that are decorated.

A religious supply shop named the Wang Family Paper Horse Shop is shown, stacks of paper pavilions of the type that were burned and offered to ancestors during the Qingming Festival in front. However, no customers are in the shop as one would expect them to be if it were festival time, and such paper pavilions were sold throughout the year to be burned at funerals. The idea was that burning them would provide deceased relatives a comfortable place to live in the underworld.

Two women are shown standing by a basket of willow brooms, a possible clue as family graves were swept during the festival. However, brooms were used year round, so the brooms are slim evidence.

Evidence that the scene was not about the Qingming Festival includes a vendor selling what appear to be melons, which would not have been in season at the time of the festival. Some scholars argue that the items could have been rice dumplings used to celebrate the festival. A banner outside a tavern also says “Xin jiu,” or new wine. Wine was not ready or “new” until fall.

Several men in the painting aren’t wearing shirts or wear straw and bamboo hats that would be worn during hot times of the year and a man holds a fan, indicating the weather was hot, but some scholars have argued that some people carried fans year round so they could cover their faces when they didn’t want to talk to people.

2. The painting is widely believed to be of the Song dynasty capital of Kaifeng and the river is believed to be the Bian River, a major transportation canal that ran through it during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). However, this has been questioned.

Some scholars such as Valerie Hansen of Yale University have argued that the scroll depicts a general vision of an idealized city rather than Kaifeng because all of its details are generic and Kaifeng landmarks of the era that are known from other historical sources don’t show up in the painting. She insists that no pagoda, temple, building or palace known to be specific to Kaifeng is shown, and shops, gates, inns and bridges like the ones in the painting were present in many 12th-century cities. The many multi-storied buildings of Song-era Kaifeng are not shown. She believes that the artist deliberately left out marks that could have identified the city as Kaifeng.

The painting left out most poor, sick and handicapped and soldiers except for a few guards taking naps. Almost everyone in the scroll appears happy and clean, and the people are dressed in stereotypical clothing for their stations. The city gate connects to a wall that has fallen into disrepair, and the wall does not resemble 12th century walls that surrounded Kaifeng. Kaifeng’s walls were manned at all times by troops because the city was intermittently under siege from invaders. It had sophisticated ramparts not shown in the painting. Only one wall is shown, although two surrounded Kaifeng. No specific location in Kaifeng corresponds to the configuration in the scroll.

Hansen’s explanation falls within a Chinese tradition of idealized landscape painting. Even maps of capital cities and other walled towns were often drawn with idealized straight walls that differed substantially from the reality.

Scholar Fu-Tsung Chiang, in the article A City of Cathay, argued that the painting showed the placement of bridges, shops, clothing and pavilions realistically, and that that would only have been possible if they were done by someone who had been at the real location. The details of the painting corroborate roughly with Song dynasty writings describing similar features of capital life.

Some scholars believe that the scroll was made specifically for a Northern Song emperor, which is plausible because the Song emperors highly valued painting and court painting during the Song dynasty made important advances especially in representation of landscapes. However, other scholars think the scroll was in private hands until much later.

3. The artist is somewhat of a mysterious figure. There is just one record of the Zhang Zeduan who supposedly painted the scroll – a colophon on the scroll itself that attributes the scroll to him. It is from 1186, much later than he is believed to have painted the work. It reads:

"Hanlin (this probably refers to a scholar of the imperial Hanlin Academy) Zhang Zeduan, styled Zhengdao, is a native of Dongwu [now Zhucheng, Shandong]. When young, he studied and traveled to the capital for further study. Later he practiced painting things. He showed talent for ruled-line painting, and especially liked boats and carts, markets and bridges, moats and paths. He was an expert in other types of paintings as well.

“According to 'A Record of Mr Xiang's Views on Paintings,' Regatta on the Western Lake (Xihu zhengbiao tu) and Peace Reigns Over the River (Qingming shanghe tu) are placed in the category of inspired paintings. The owner should treasure it.

“On the day after the Qingming festival, in 1186, Zhang Zhu from Yanshan wrote this colophon."

Some scholars believe the scroll could have been painted after the 1127 fall of Kaifeng and the Song dynasty, as it is in the same style of paintings at Yanshan Monastery at Mount Wutai in China that dates to 1167. However, others believe that the monastery paintings were done by a painter who was trained in the Northern Song court before it fell.

The mysteries associated with the scroll and its rich visual content about the Song Dynasty era have spawned an entire genre of historical and cultural studies and scholarly conferences where experts from a variety of disciplines have shared findings of their research.

The scroll is of a genre of horizontal long scrolls that the viewer held in both hands and unrolled slowly from right to left so that the painted scene would unroll gradually. The idea was that such a scroll was a vicarious journey. Hand scrolls incorporated moments of suspense that enticed viewers to continue looking at the painting.

The scroll gave the viewer the impression that he was moving along the river seeing new scenes unfold as he unrolled the scroll. Most of the scroll appears to show the viewer looking down on the scene, but in the center of it, the point of view drops so that the underside of the central bridge can be seen. The artist also moved back to show many shops and people in this part of the scene.

The scroll has a convoluted history, having gone from imperial collections to private ones and back at least four times. It apparently was stolen from the imperial collection as early as the 1340s. Emperors repeatedly recovered it when confiscating wealthy estates during judicial or political disputes, so it became part of the history of relations between the court and the wealthy class.

When the last imperial emperor, Puyi, was forced out of the Forbidden City in Beijing in 1924, he took it with him. Japanese invaders later installed him as a puppet emperor when they took over Manchuria. When the Japanese were defeated in World War II, the Soviet army captured Puyi and the scroll. They deposited it in a Chinese bank in northeastern China for safekeeping while the Chinese Communists and Nationalists fought a civil war over which party would control China. After the Communists won, the bank turned the painting over to a local museum which sent it to Beijing to return to the Forbidden City. There it sat until someone happened upon it in the palace collection in 1954. Since then, it has been carefully cared for and exhibited only occasionally, in low light. When we first saw it in the Forbidden City, we were free to gaze at it as long as we wanted to. However, on the rare occasions when it is exhibited now, guards quickly usher viewers past who have waited in line for hours to see it.

Surprisingly, the scroll is in good condition with only a few patched pieces and a pattern of fine cracks in its surface. It is possible because of the many times that it has changed hands that it is a forgery, but art scholars agree that there is no evidence that it is. The style and materials are consistent with paintings of the era it is believed to have been created in, and seal marks that its various owners placed on it over the centuries are historically accurate.

The painting was a favorite of a number of emperors and the literati.

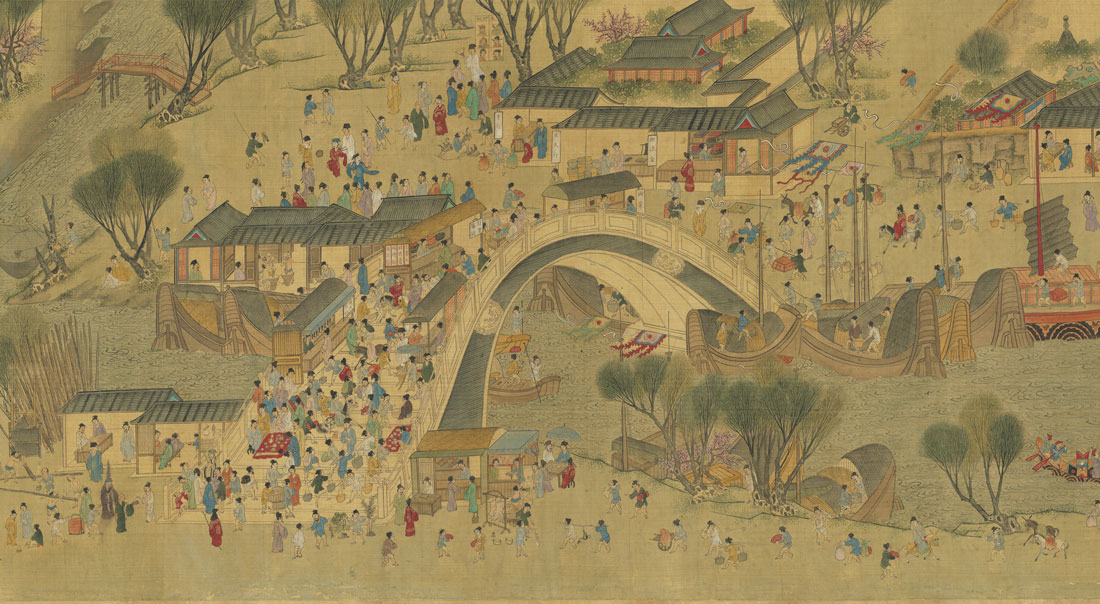

An early remake, considered to be faithful to the original, was made by Zhao Mengfu during the Yuan Dynasty. Among the famous versions now considered priceless is one done in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) by master artist Qiu Ying. Qiu’s painting depicts his home city of Suzhou, not Kaifeng. The buildings are grander and more spacious. Some landmark buildings in Suzhou are recognizable, and the painting has bright green mountains and other colors. The scroll includes details such as soldiers wielding the Ming flag that are not in the original. A leader on horseback is shown along with flute players and soldiers with weapons. This indicates that Qiu placed a political message of Ming power in the scroll. The clothing, boats and carts are Ming style. The boat is being guided under the bridge by ropes pulled by men ashore while several other large boats wait their turn. The idea was to depict the prosperity of the Ming dynasty. The painting is more colorful, but far less spontaneous looking than the original painting.

The most famous reinterpretation of the painting was created by five court artists in 1737 during the reign of the emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) of the Qing Dynasty. The Qing version has colors that are an example of Western influence in the Qing court, which employed Italian Jesuit artist missionaries who introduced Western painting techniques and color.

In the Qing version, the rainbow bridge is a tall, wide stone bridge with stalls built into both sides. Beneath the bridge, water moves in the opposite direction of the original version, and the boat moves against the flow of the river. Polemen under the bridge and boatmen with ropes act in unison to guide the boat, although a few on the boat and bridge appear to be yelling at each other.

Watch the image below change to show the bridge in its monochrome version from the Song dynasty, then in a Ming dynasty version and finally in a larger version from the Qing dynasty. To stop the images from changing, mouse over the image.

- ⋅

- ⋅

- ⋅

There are many more people, more than 4,000, in the Qing remake, which is much larger at 37 ft by 1 ft. The overall message of the scroll is much different than that of the Song original. The Qing version sacrifices the intimacy and realism of the original to show the grandeur of the empire – with sweeping views of water with boats in the distance and the left side taken up by a fairy-like garden palace like those in which the Qing emperors lived.

An irony of the Song and Qing versions is that during the Song Dynasty, China was under constant attack from aggressive northern nations such as the Manchus, who later conquered China and became the Qing dynasty. The Manchus considered themselves the saviors of the Chinese empire that they reunited, and the Qianlong Qingming scroll reflects that. It is an idealized version of a vast, orderly, peaceful China. The Qing Dynasty scroll’s own history belies that unity, however. It was among treasures from the imperial collection that were removed from Beijing by the Nationalists in the 1930s, when Japanese invaders threatened and then conquered Beijing. The scroll was moved to Taiwan in the 1940s during the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists and is now in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan.

The Song Dynasty original and the Qing dynasty version are regarded as national treasures by both the Communist government in Beijing and Taiwan's government and are exhibited only for brief periods every few years.

The painting has been copied in embroidery, carpets, wood carvings and black granite as well as lesser items. Small versions of it are sold on Amazon and at museums in China. We own a blue and white porcelain brush pot that depicts the painting's gate scene and the surrounding neighborhoods. The pot draws from the Chinese ceramics tradition of wrapping designs of famous scroll paintings around vases.

We also own a thousand-piece puzzle of the bridge scene in the scroll. It almost did us in one holiday season, because its monochrome nature made it by far the most complex puzzle we've ever assembled. It was a marathon and in the end, we had three or four pieces in the water sections that were in the wrong place and we never got them sorted out.

There is a tourist theme park in Kaifeng based on the painting. About ten years ago, an animated exhibition based on the scroll was created. It was 110 meters by 6 meters and took two years and 2,000 people to create. It had 1,068 characters that moved in a four-minute loop showing a transition from day to night. A river of light flowing alongside the scroll lent to the impression that viewers were watching the scroll from across the river.

The exhibition attracted huge crowds who watched in fascination as familiar characters on the scroll moved over the bridge and boats sailed on the river. Created by Crystal Digital Technoiogy Ltd., the project was lauded in China as a link between a prosperous and technologically advanced historical era and China’s current rise. The Song dynasty saw the invention of moveable type, the compass, gunpowder and paper money as well as some of China’s finest art and cultural achievements, and it is seen as an advanced, well-governed, orderly and prosperous era that is a model for today’s China. The exhibition was first shown at the Shanghai World Expo 2010 and then traveled to Singapore, Hong Kong, Macao and Taipei, Taiwan. More than 10 million people saw it.

The wooden bridge depicted in the original version of the scroll was rebuilt by a team of engineers and documented by the PBS television show NOVA during their Secrets of Lost Empires series.

Next week: How the Qingming painting's content has retained its relevance over the centuries.

Check out these related items

The Many Layers of Mona Lisa

Mona Lisa has long been mysterious, not just because of her smile. But was mystery or realism her famous creator's object?

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

Inside a Chinese Painting

Take a quick break and enjoy spectacular scenery on a boat trip down the Li River near Guilin, China.

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

China’s Export Porcelain

Chinese porcelain is durable and branded with its history, so it is used to trace China’s trade and cultural ties with other nations.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.