Treasure Room and Two Palaces

Photos by Forrest Anderson and historical images

Away from the crowds of tourists moving through the grand rooms of the French castle Fontainebleau is a quiet, darkened treasure room that houses a bizarre and exquisite collection of Asian artifacts. It is here that France keeps the Qing dynasty artifacts that Napoleon III’s troops looted from the Chinese emperor’s summer palace, Yuanmingyuan, in Beijing in 1860.

A jewel-encrusted golden stupa flanked by two elephant tusks, bronze dragons, fine porcelain, carved jade, cloisonné vases that French Empress Eugénie had French craftsmen make into a chandelier and candlesticks and bejeweled gold jewelry vie for space in crowded Chinese-style cabinets. On the ceiling are Tibetan thangkas taken from Yuanmingyuan. The items are in pristine condition, as though they had just been shipped from Chinese imperial workshops. They are clearly top-of-the-line Qing imperial artifacts, in the same class with 18th and 19th century artifacts in the imperial collections in Beijing and Taipei, Taiwan.

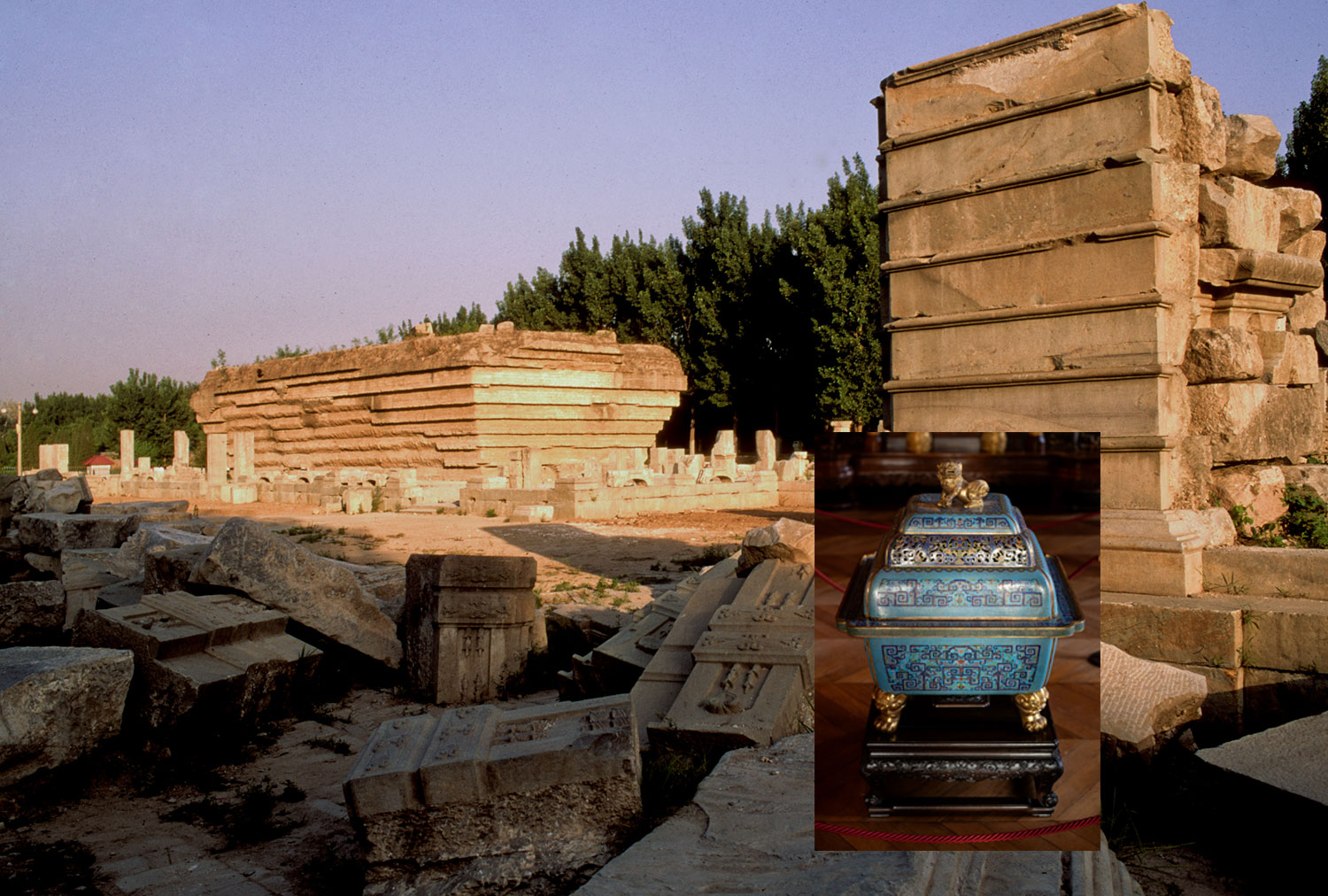

Thousands of miles away in Beijing, the stone ruins and foundations of what once was described as a fairyland of palaces, gardens and lakes are almost all that remains of Yuanmingyuan, China’s Garden of Gardens.

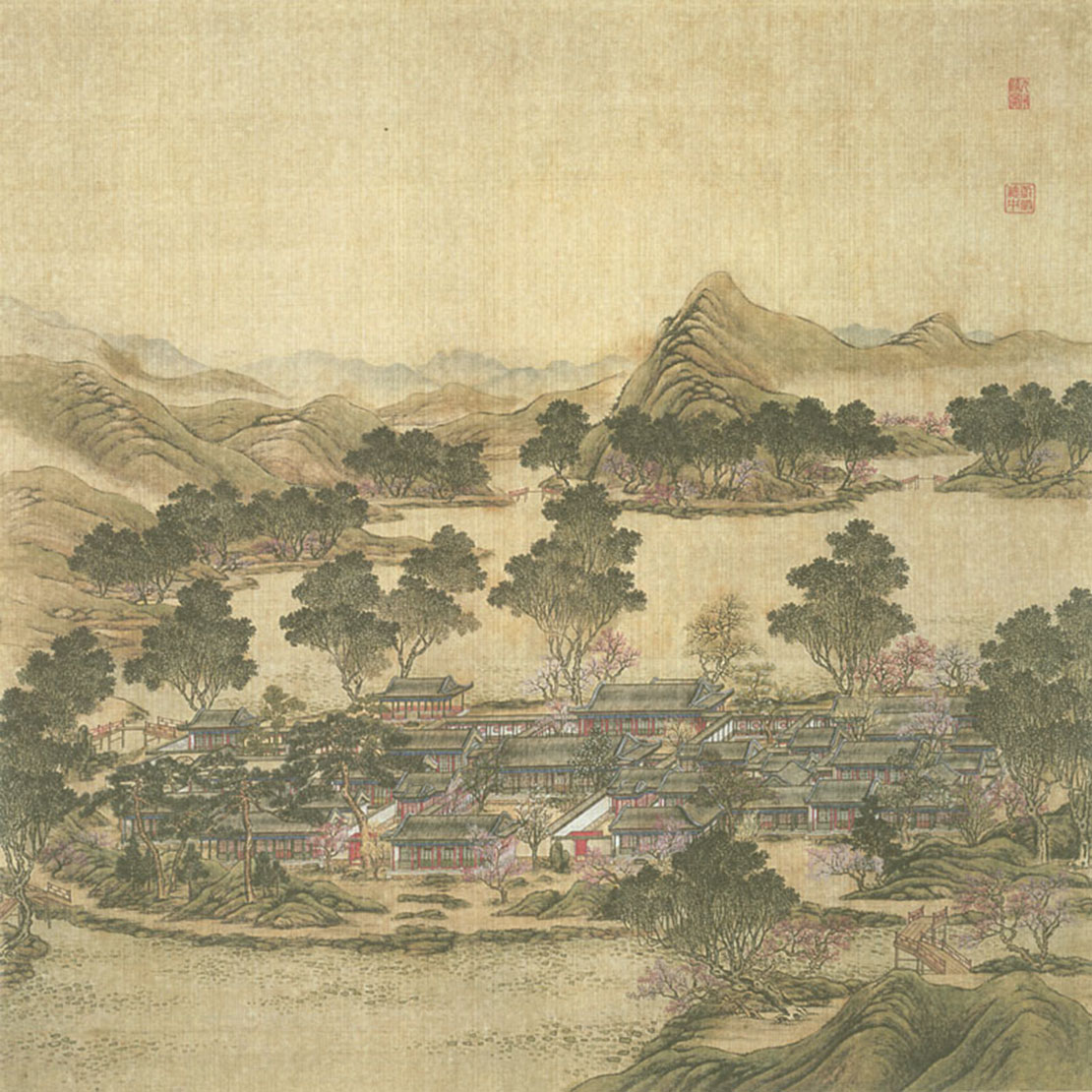

The story of how the palace and its treasures came to fall into French and British hands is one of the most painful episodes in 19th century Chinese history. The garden was the creation of the three great emperors of the Qing Golden Age in the 18th century – Yongzheng, Kangxi and Qianlong. It included hundreds of palaces and buildings artfully arranged around lakes with valuable trees and plants that were collected from all over China. The palace was an idealized microcosm of China, with 40 scenes designed to imitate famous scenic views around the empire, several libraries of priceless historical documents and treasure halls filled with the finest of Chinese porcelain, bronze vessels, sculpture and paintings not just from the Qing dynasty but dating back thousands of years.

The Chinese emperors much preferred the garden to the stifling ceremonial palace compound, the Forbidden City, in the heart of Beijing and they lived at Yuanmingyuan except for when they needed to conduct official business at the Forbidden City. Yuanmingyuan was a world unto itself, with religious temples, an ancestral shrine, a school for the princes, government offices for officials, a shopping street and even fields cultivated by eunuchs. There, the emperors worked at governing but also relaxed in lake-side pavilions, enjoyed theatrical performances, wrote poetry, practiced calligraphy and grew prize peonies. Most of the gardens were Chinese style, but the emperors also satisfied their curiosity about the Western world by building a complex of Western-style palaces with fountains, collections of Western clocks and other curiosities.

Source: MIT

At their height under Qianlong, the gardens were described as overwhelmingly beautiful. In 1793, visiting Lord Macartney said he saw 40 or 50 different palaces or pavilions. “These are all furnished in the richest manner, with pictures of the emperor’s hunting and progresses, with stupendous vases of jasper and agate; with the finest porcelain, and with every kind of European toys and sing-songs; with spheres, orreries, clocks, and musical automatons, of such exquisite workmanship, and in such profusion, that our presents must shrink from the comparison, and hide their diminished heads; and yet I am told, that the fine things which we have seen are far exceeded by the others of the same kind in the apartments of the ladies, and in the European repository at the Yuen-min-yuen.”

By 1860, the Chinese empire was in decline and the gardens, according to 19th century visitors, were run down. However, they were still a treasure trove.

The sacking of the garden was the culmination of almost thirty years of intermittent conflict between the rising British and French empires and China over trade, a period called the Opium Wars. It is beyond the scope of this account to recount the details, but the gist is that China’s Qing dynasty emperors since the 1760s had restricted trade with foreigners to a designated strip along the Pearl River in Canton, now the city of Guangzhou. This system worked well for both Chinese and Europeans until the early 19th century, when the British and French began to push for rights to trade at other Chinese coastal and river ports. Among products they traded with China was opium, which spawned a nationwide addiction epidemic that prompted the Qing government to push back by banning trade in the drug. As the British and French empires became more aggressive and the Chinese empire declined, the dispute escalated into intermittent armed conflict and the signing of an 1842 treaty opening more ports. When China dragged its feet in implementing the treaty, British and French forces sailed north in 1860 to invade China and force the Chinese to open more ports, allow their countries to have resident ambassadors in Beijing and pay for the military costs of the conflicts.

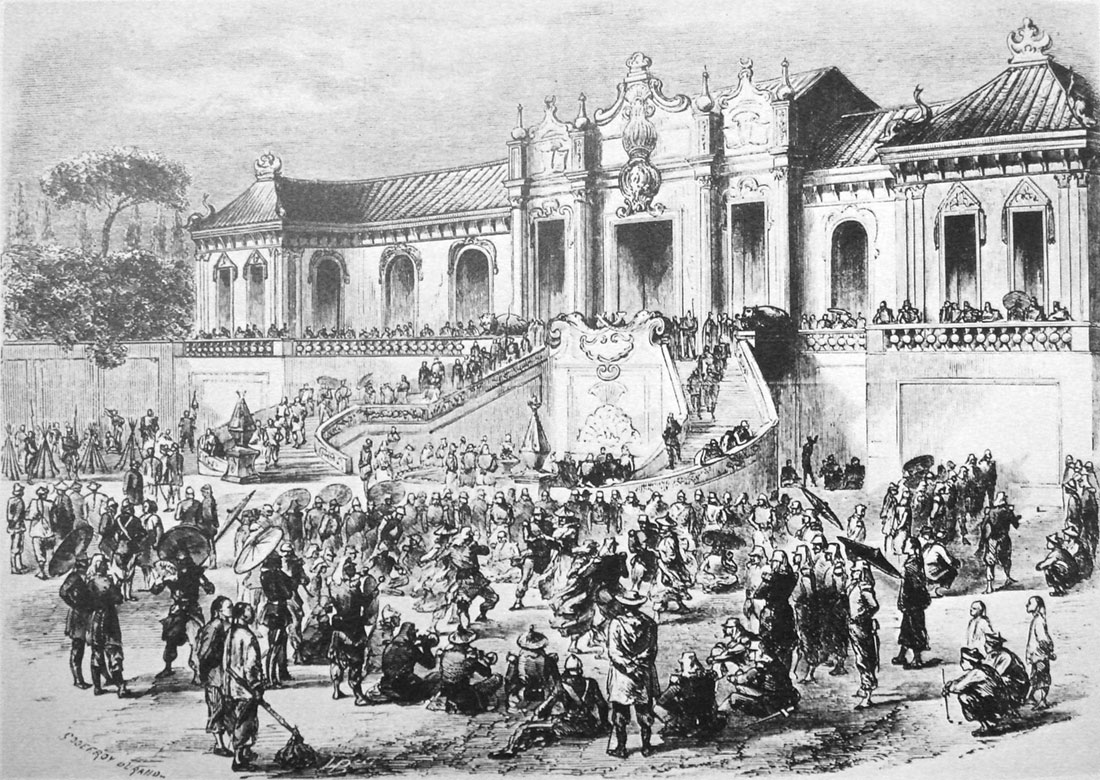

As the Anglo-French forces neared Beijing, Chinese officials detained and imprisoned an advance party sent to negotiate under a prearranged flag of truce. The foreign armies advanced to Beijing and French forces on October 7 broke into Yuanmingyuan, which the emperor and his entourage had vacated and which was guarded only by a few eunuchs. Soldiers lost control, running around in an orgy of indiscriminate looting. They lifted everything they could and destroyed objects that were too heavy to be removed. The British joined in. Priceless treasures were carted out of the palace and crated for shipment to Europe, where they now reside in some 47 museums and in private collections.

On October 8, the Chinese government capitulated to demands for the return of the advance party and returned 19 of them alive and the others as mutilated corpses in coffins.

The evidence of torture further incensed the foreign troops, who demanded that the Forbidden City be burned in revenge. The British commander, Lord Elgin, refused to go along with that, repelled by the cultural destruction and fearing that the Qing government would fall and the Western allies would be stuck with an unwanted empire. However, Elgin reluctantly agreed to the destruction of Yuanmingyuan, believing that that act would hit home with the Qing emperor because it was his personal residence.

The troops systematically set fire to the buildings and let them burn to ashes over a period of several days.

To the Qing government’s relief, the foreign armies stuck to their original limited goal of forcing ports open for foreign trade and once they had rung an agreement from the Chinese to open the ports and pay reparations, largely withdrew except for establishing embassies in Beijing. However, they had brought the Qing government to its knees. Thereafter, foreign powers forced it to sign a long series of “unequal” treaties that by the 20th century had opened most of the Chinese coast and rivers to foreign trade and manipulation. The Qing government managed to cling to its fragile power mainly because the foreign powers were primarily interested in making money, not acquiring another India-style empire to govern, and because they were distracted by quarrels among themselves. In 1912, the Qing fell, ushering in the violent 20th century of warlords, civil war and finally the Chinese Communists’ rocky rise to power and repressive rule.

The modern Chinese position on the Opium War is harshly critical of the foreign invaders who burned the palace as well as of the weakness of the Qing government, itself made up of foreign Manchus who had invaded China in 1644 and overthrew the native Chinese Ming dynasty.

The Chinese Communists regard the humiliation of the foreign invasion and the burned and looted palace as one of the key episodes in their fiercely nationalistic grievance-based state ideology. This position was given a huge propaganda infusion after the 1989 Tiananmen protests and crackdown in a bid to rebuild public support for the government and cast the Communists as the sole force enabling China to overcome its humiliation at foreign hands.

At their historic heart, the Yuanmingyuan treasures at Fontainebleau are the tale of two empires. France under Napoleon III doubled the area of its overseas empire, colonizing in southeast Asia and parts of Africa, building the French Navy into the world’s second most powerful after Britain’s and creating a colonial army. Ultimately, the expense of the empire overwhelmed its profits, but it was on the rise in 1860.

When the Yuanmingyuan treasures arrived in France, French Empress Eugénie watched the opening of the crates and selected what she wanted from them. In 1861, the collection was supplemented when the King of Siam made a celebrated visit to the French court and gave many gifts to Napoleon III. Other Asian artifacts previously in the possession of the French court and from an estate sale of the emperor’s half-brother were added to the collection along with some Vietnamese and Japanese objects. Because the army’s inventory of the Yuanmingyuan items was not detailed, it is uncertain whether some items are from Yuanmingyuan or were acquired elsewhere. Some are believed to have been confiscated earlier during the French Revolution by the government from French aristocratic families.

Eugénie exhibited the items and then put most of them in storage while she displayed some in her study and painting studio at the Tuileries Palace in Paris. A few ended up in other museums or libraries. The Qianlong emperor’s parade armor, for example, is in the Artillery Museum in the Hotel de Invalides. In 1863, the empress converted some rooms that had been vacated by the Grand Marshal at Fontainebleau into a salon and gaming area. Part of these plans included a museum to display her Asian collection.

It was popular in this age of empire for European aristocrats to have a cabinet of curiosities, often with prized pieces of Chinese porcelain. Because Eugénie was an empress, she got an entire room. The lacquer panels on the walls were from two large screens that had been in the royal furniture collection well before the 1860s.

In the pride of place are the stunningly beautiful gold Tibetan stupa inlaid with turquoise stones, flanked by elephant tusks and gilt bronze dragons. Large cloisonné incense burners are nearby. Around the walls are carved Chinese-style cabinets commissioned by Eugénie and stuffed in 19th century fashion with fine porcelain, carved jade and cloisonne in mint condition. The visitor peers through the low light into glass cabinets filled with stunningly ornate gold and jeweled items. A sign in English and French says that the French army plundered the artifacts from Yuanmingyuan. The collection is overwhelming in its beauty and quality.

The position of the staff at Fontainebleau has been that the collection is not just an example of Chinese imperial arts, but part of the history of the French empire and as such should not be broken up. This view was behind the 1980s restoration of the rooms and collection to the way they were in Eugénie’s museum. Eugénie personally supervised the placement of the artifacts in the museum, and they were placed in the same places in the seven-year restoration done with the help of palace inventories and 1863 photographs of the rooms. The French emperor and empress and their guests used the room frequently to relax and play games in the evening until 1868, the last time they visited the palace. The result of the restoration is that a visitor feels oddly as though they have dropped back into the Empress’s quarters while she just stepped out for a moment.

The day we visited, we were alone in the room except for a bored guard for most of the time. Two or three Chinese visitors, commenting quietly to each other in Mandarin and taking pictures with their phones, toured the rooms quickly and left silently.

What goes around comes around. Napoleon III and Eugénie, the last emperor and empress of France, were deposed in 1870, so the Qing dynasty outlived their reign by another 42 years. Napoleon III died in 1873 and Eugénie lived privately as a widow until years.

The Prussians took over Fontainebleau briefly in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. The collection was disputed in litigation for almost a decade before the French state was awarded ownership in 1879. Presumably, the Chinese were not a party in the litigation. The French government has controlled the collection ever since.

The rooms were opened to the public as a museum, but the furnishings were removed until the 1980s restoration.

The Chinese government has recovered only a few treasures from Yuanmingyuan. In 2014, Beijing University alumnus Huang Nubo donated $1.6 million to the KODE Art Museums in Bergen, Norway, after weeping when he saw columns from the Yuanmingyuan there. Shortly thereafter, the KODE returned seven of the columns to China. Huang has denied that the return was connected to his donation. China has recovered several of the 12 bronze heads of the zodiac animals that once graced a clock water fountain in Yuanmingyuan. In 2013, two of the zodiac heads, the rabbit and the rat, from the estate of the French designer Yves Saint Laurent, were handed over to China after a planned auction was canceled. Officials in China told Christie's, the auction house, that if the heads were sold, there would be “serious effects” on the firm's business. Not long after the heads were returned, Christie's became the first international fine-art auction house to receive a license to operate independently in China. China Poly, a behemoth Chinese corporation and global arms dealer, has an offshoot firm called Poly Culture that has bought and returned to China four of the zodiac heads. Originally, one of the heads spouted water every two hours and all of them spouted water at noon.

Liu Yang, a Chinese researcher, made an exhaustive search of museums and created a book listing Yuanmingyuan treasures in 2009.

In 2015, thieves broke a window in Fontainebleau, climbed in and stole porcelain vases, a coral, gold and turquoise mandala, a cloissonné chimera, a replica of the crown that the King of Siam gave Napoleon III and other items in a seven-minute heist. Museum officials said it was clear that the thieves had a list of items they wanted to take.

The robbery was among a rash of similar heists in Europe. They included a 2010 one at the Chinese Pavilion at Drottningholm Palace in Stockholm, Sweden and another a month later at the KODE Museum. Thieves also struck the Oriental Museum at Durham University in England and a museum at Cambridge University. In 2018, thieves took another 22 artifacts from the KODE Museum.

The thefts appeared to have targeted specific art and antiquities from China, particularly those looted by Western armies. After the heists, the items, many of which are documented and well-known, did not appear on the antiquities market but simply disappeared without a trace.

Since then, some museums have quietly shipped crates of art back to China in hopes of avoiding trouble with thieves or pressure from the Chinese government to return them.

However, many foreign institutions have been reluctant to return artifacts to China not just because of the immense monetary, historical and artistic value of Yuanmingyuan items but also because of China’s dismal record of caring for historical treasures. During the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, art was considered decadent and countless priceless antiques were smashed by gangs of revolutionaries who rampaged through historical sites destroying them and their contents. As China emerged from that era, stealing valued artifacts from museums and shipping them to Hong Kong became lucrative and often occurred with the collusion of museum employees. Many museums in China also were strapped for cash and unable to properly care for their collections.

By the early 2000s, China was more affluent and was regaining a sense of pride in its culture and long history. The government used art plundered from China to stir up a sense of nationalism. In 2009, the Chinese government sent a treasure hunting team to institutions in the United States and Europe to look into what Chinese treasures were on display at them. One Chinese government estimate is that more than 10 million artifacts have been taken out of China since 1840. Those most important to China are those taken out from 1840 to 1949, which the Chinese call their Century of Humiliation. Return of looted objects, most importantly Yuanmingyuan pieces, are considered an important symbol of China's recovery from that period of national decline.

The country’s many billionaires have driven the prices of Chinese artifacts to astronomical levels to demonstrate both their wealth and patriotism. China’s wealthy are a third of the global art auction market. In 2010, a Chinese vase sold for $69.5 million.

Antiques connected to China’s imperial past or humiliating events such as the sacking of Yuanmingyuan sell for millions of dollars, usually to these billionaires. Billionaire Liu Yiqian bought a small porcelain cup that was once part of the imperial collection for $36 billion and then shocked the art world by drinking from it. He later paid $45 billion for a Ming-dynasty Tibetan tapestry.

The Yuanmingyuan looting and fire are among a number of events that contributed to major losses of significant historical artifacts from China. Another was the 1900 occupation and looting of the Forbidden City, royal gardens, government buildings and houses by an invading force of British, US, German, French, Russian, Japanese, Italian and Austrian armies.

The 1860 and 1900 events also contributed to the exportation or destruction of volumes of the 600-year-old 11,095-volume Ming-dynasty Yongle Encyclopedia. The remaining volumes are scattered in a variety of museums and private collections in the United States, Britain, Germany, the Republic of Korea and Vietnam.

Other disputed items include 9000 volumes and 500 paintings taken from Dunhuang in northwestern China in 1907, now in the British Museum in London and in India, and other Buddhist documents and murals taken by French, Japanese, Russian and U.S. explorers that are in major museums abroad. In 1908, Russian explorers took a large cache of ancient statues, books, documents, coins and jewelry from the deserted city of Heishui in northern China. They are in Russian museums. Documents and art from three ancient oases kingdoms in Northwest China were taken by French, British, Swedish and Japanese explorers and are in major museums in their countries. Pictographs inscribed on tortoise shells and bovine bones found in the remains of the last capital of the Shang Dynasty (16th-11th centuries BC) in China were purchased by foreign collectors and institutions in the early 20th century and are in museums in 12 foreign countries.

Experts both foreign and Chinese, while decrying the deportation of these valuable artifacts from China, quietly acknowledge that had they not been taken out of China, many would have been destroyed in China’s wars and the Cultural Revolution. Having looted the items, the best foreign museums and libraries have largely taken good care of them. It is not clear that this would have happened in China.

Some experts even privately express the sentiment that the items still may be better off in foreign institutions given the Chinese government’s propensity to use historical artifacts as pawns in its current political agenda and the powerlessness of Chinese historical institutions to push back.

The loss of historical knowledge that accompanied the wrenching of artifacts from their environment and the destruction of many others, on the other hand, is universally denounced by Chinese and foreign historians, archeologists and museum experts.

In an effort to partially rectify this, Chinese and foreign experts collaborate in sharing knowledge about artifacts located in different institutions, holding conferences and exhibitions and publishing papers, books and on-line databases that gather knowledge about their disparate collections.

After the destruction of Yuanmingyuan, the Qing court relocated to the Forbidden City and restored the nearby Summer Palace, which had been looted but not destroyed. It became the favorite resort of China’s late-19th century ruler, the Empress Dowager Cixi.

Today, the ruins of the European-style palaces at Yuanmingyuan are the site's most prominent remnants, leading some visitors to erroneously assume that they were the main buildings at the garden. A few Chinese-style buildings in Yuanmingyuan survived the 1860 fire but were burned by Allied forces in 1900.

Ironically, there are parallels between the design of the Chinese European-style palaces and Fontainebleau, among them the large horseshoe-shaped stairway. This is clear in the sketch of the looting done by the army in 1860 and a photograph of Fontainebleau, where restoration work is being done.

Source: Godefroy Durand - L'Illustration, 22 December 1860

The Yuanmingyuan site was turned into a park and historical site in the 1980s. In the 1990s, a debate arose over whether to rebuild the garden or keep it in ruins as a witness to the destruction wrought by foreign powers.

A few buildings have been rebuilt and the lakes dug out and refilled. Brush has been cleared, and the foundations of some of the destroyed buildings have been uncovered. A project to line the lake beds with a membrane that reduced seepage from them was controversial because the park’s ecology and Beiijng’s underground water system were thought to be affected.

China and France are not likely to go head to head over the Yuanmingyuan treasures any time soon. While relations between the two countries occasionally hit bumps, the two countries have largely worked out their original trade dispute. China is France’s second largest supplier of trade goods after Germany while China is the seventh largest market for French exports.

Check out these related items

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.

Tiananmen Square

China's Oct. 1 celebration of 70 years of Communist rule centers on Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s most controversial places.

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

Britain and Greece’s Parthenon Dispute

What are the chances that two men from one family set off international disputes by carting off treasures from Greece and China?

Islam in China

Muslims in China are a diverse religious and cultural group with a tumultuous history who take various sides in political disputes.