Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

Photos by Forrest Anderson

The narrow strip of land west of China’s Yellow River called the Hexi corridor has been the western gateway to China for more than two millennia. On that corridor’s western end is the oasis town of Dunhuang, poised on the edge of the Taklamakan desert. For long periods of Chinese history, the region marked the western limits of Chinese imperial power.

Today, this ancient city is at the vortex of a surge of international research about the ancient Silk Road trade routes of eastern Central Asia, centering around the vast complex of Buddhist caves at nearby Mogao and its unparalleled library of ancient documents.

Technology has met the ancient world in this endeavor, bringing the documents, caves and other artifacts together in an on-line collaboration that is enabling researchers worldwide to open new lines of inquiry into the history of Central Asia.

Dunhuang was founded in 111 BCE as a Chinese military colony after Chinese forces subdued the nomadic Xiongnu people of the area between 121-119 BCE. Two thousand Chinese soldiers in Dunhuang guarded routes by which the Chinese imported and exported silk and other goods to the west and received western goods. The Dunhuang region still has the ruins of defensive walls, dozens of watchtowers, forts and supply depots from this period and the later Tang dynasty (618-907).

Dunhuang became one of the most important stops along the routes from the Middle East to China, subject to cultural influences from merchants and others who settled there or passed through. These people built temples in Dunhuang for Buddhist, Daoist, Nestorian Christian, Manichean and Zoroastrian worship. Some of these foreign peoples became officials and soldiers for China. The region was host to Buddhist monastic communities as Buddhism spread west into China. The most important early translator of Buddhist scriptures in China, the monk Kumarajiva, worked at Dunhuang. Famous Buddhist pilgrim monks Faxian and Xuanzang passed through Dunhuang en route to or from India.

According to tradition, a monk had a vision of the Buddha gleaming in a sunrise over Sanwei Mountain near Dunhuang in 366, and built a small cave in the cliff face to meditate. He placed a small statue in the cave. Soon other monks followed suit and a monastery was founded in the man-made caves at the site. The monastery grew to 1000 caves. Five hundred caves containing statuary and paintings still exist as well as an additional 300 undecorated caves that monks used for living and meditation quarters. The earliest caves contain intact images dating to the early fifth century, while the last ones with significant decoration were created in the early 14th century.

This near millennium of artwork constitutes an unparalleled record of the development of Buddhist architecture and imagery as well as the history of the Silk Road routes. The early artwork shows direct influence from India, Central Asia and China. Over time, the art merged into a uniform Chinese Buddhist style. Beginning in the 10th and 11th centuries, when the Tang dynasty declined, the Tibetans conquered Dunhuang and the paintings took on Tibetan influence until the Tibetans gradually withdrew. The images depict incarnations of Buddhas, illustrations from sutra texts, scenes of paradise and inscriptions and depictions of monastery patrons and their protectors.

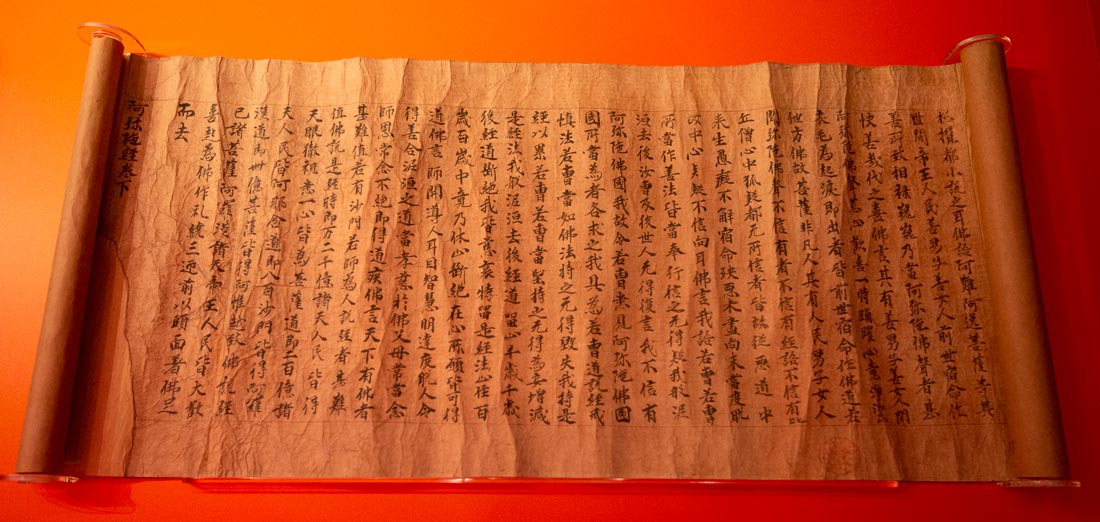

The Sutra of the Ten Kings, which depicts ten stages that the soul passes through after death. The 10th century scroll is from Dunhuang. It is part of a major exhibit on Buddhism now open at the British Library. Many of the manuscripts, artifacts and murals from the Dunhuang caves are rich sources of information about ancient beliefs and lifestyles.

More than 1,000 years ago, monks and nuns for unknown reasons gathered together scriptures and paintings of the Buddha used in ceremonies and festivals at Mogao and placed them in one of the caves. They plastered over the cave’s wooden door and painted over it to hide the entrance.

Knowledge of this library was lost for 900 years until 1900, when a Taoist caretaker monk, Wang Yuanlu, stumbled upon the door, which he opened to find the library. He was unable to read the manuscripts, but knew they had to be immensely important. He contacted local officials and offered to send the documents to the Chinese capital of Beijing. However, the Chinese Qing dynasty was on its last legs and bankrupt, so the government refused. Explorer Aurel Stein, in the middle of his second archaeological expedition to Central Asia, soon heard of the discovery. Stein rushed to Dunhuang in 1906, where after two months he was able to meet with Wang and see the documents.

“Heaped up in layers, but without any order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest’s little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly ten feet, and filling, as subsequent measurement showed, close on 500 cubic feet. The area left clear within the room was just sufficient for two people to stand in,” Stein described the documents.

Wang was uneasy about selling the documents, but agreed after Stein claimed to be following in the footsteps of the Chinese monk Xuanzang who had journeyed to India in search of religious texts. Wang sold Stein 10,000 documents and painted scrolls.

News of the documents spread, and French sinologist Paul Pelliot bought a large number from Wang. Unlike Stein, Pelliot could read Chinese so he was able to select some of the best. Russians and Japanese also purchased some. By 1910, when the Chinese government caught on to the importance of the cache and ordered the remaining documents sent to Beijing, only a fifth of them remained. They are now in the National Library of China in Beijing. Thousands of Tibetan manuscripts from the cave also are in museums and libraries in the Dunhuang region. The majority of the documents removed by foreign explorers are at the British Library in London and the Bibleotheque nationale de France in Paris, but there also are many documents and artifacts in institutions in other countries.

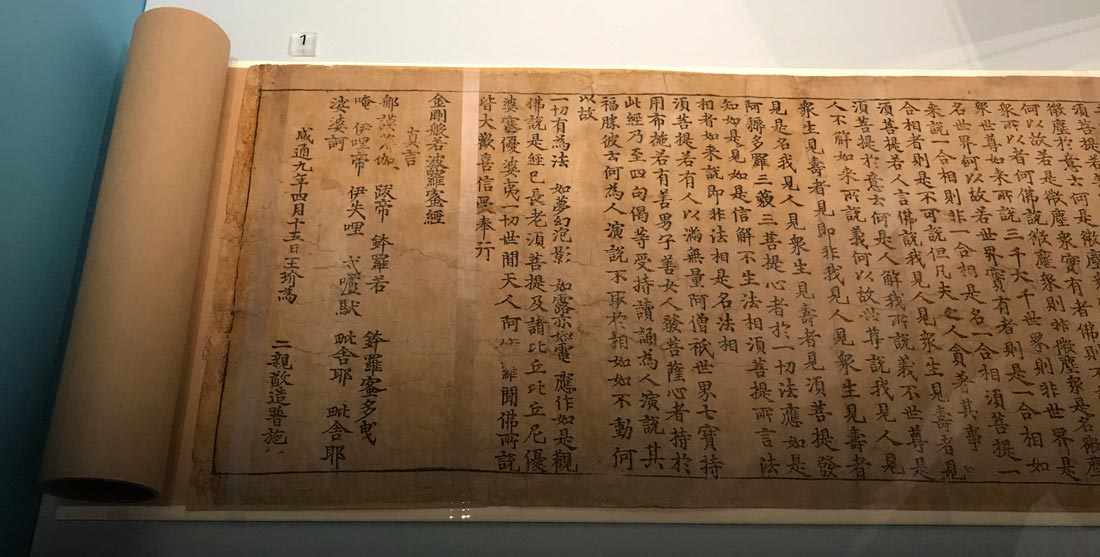

The documents include many important ones, among them the world’s earliest dated printed book, a copy of the famous Diamond Sutra printed in 868. There are thousands of other texts written in Chinese, Tibetan, Uighur, Sanskrit, Khotanese, Sogdian, Tangut, Tibetan, Hebrew, Turkic and other languages of the Silk Road.

The beginning of the Diamond Sutra, which has a colophon dating it to 868. It was commissioned by a patron in honor of his parents. The sutra, which has been painstakingly conserved, is on display at the British Library.

The cave had more than 15,000 books dating from the 5th-11th centuries. Most were Buddhist, but also some involved Daoism, Confucianism, Nestorian Christianity, Manichaeism, and non-religious topics such as astronomy, mathematics, geography, music including folk songs and dance and history. They include some of the earliest examples of Tibetan writing and various forms of both Chinese and Tibetan, including ones written in now-extinct Sino-Tibetan languages. In all at least 17 languages and 24 scripts are represented. Some of the languages are known by only a few examples.

The collection is a testimony to the diversity of Dunhuang, where Chinese scribes copied Tibetan prayers translated from Sanskrit by Indian monks for Turkish khans.

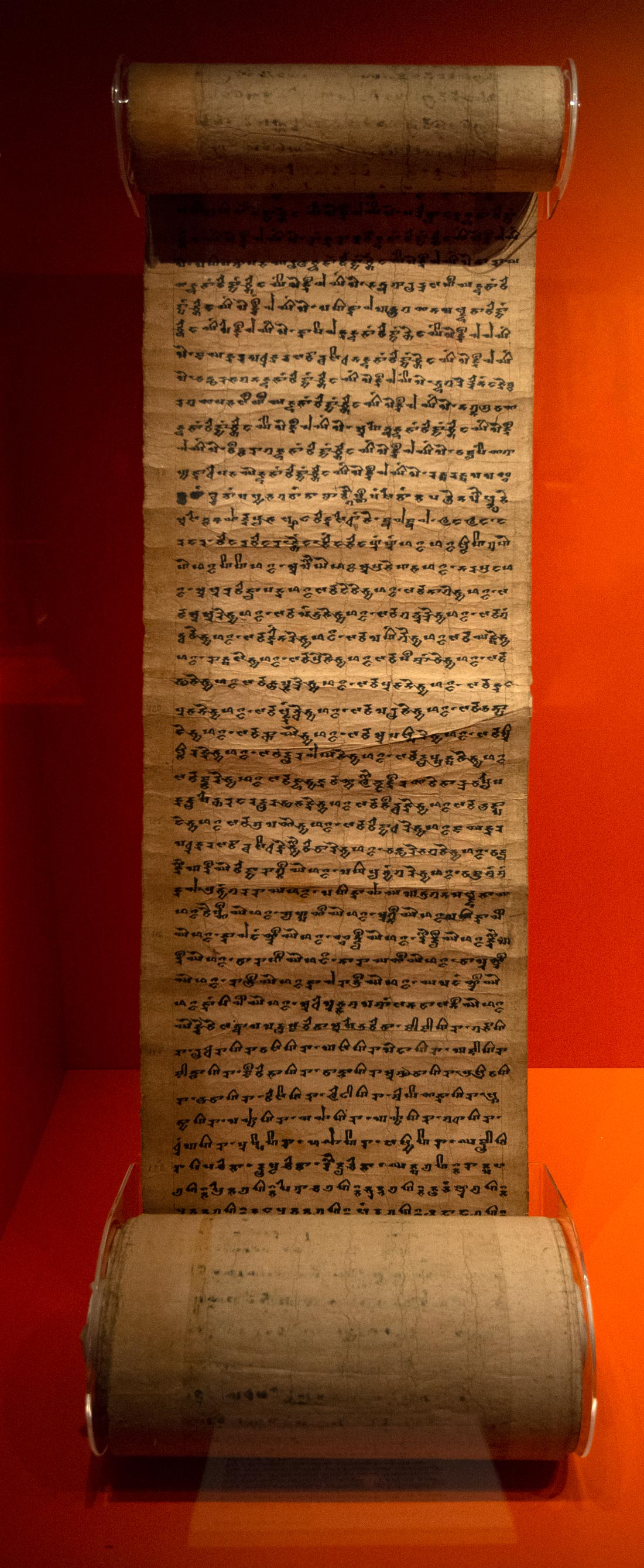

An early paper scroll in Khotanese and Sanskrit from 943. This scroll was commissioned by a patron who wanted long life for himself and his family. The scroll is on display at the British Library as part of a major exhibit on Buddhism.

The collection is one of the most important ancient libraries in the world, arguably as significant as the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi library. It includes 60,000 manuscripts, printed documents, paintings and artifacts and fragments.

Considerable written material for the early history of the Dunhuang region also has been found in the ruins of Han dynasty fortifications in the area. These extraordinary sources have allowed for detailed study of the Dunhuang region.

An entire academic discipline evolved around the materials. It is a demanding field because of the many languages and disciplines involved – history, religious studies, linguistics, manuscript studies, archaeology, architecture and art. This was made more daunting by the far flung locations of the materials. As the field developed with the opening of China and the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, which gave foreign researchers access to Dunhuang and Central Asia and sparked interest in the Silk Road, concern arose about researchers getting access to and handling the very fragile ancient documents.

These concerns meshed with the new technology of the Internet and digitization of archives to create a project that has revolutionized the study of the manuscripts and become a poster child for successful archive digitization.

An international group led by the British Library established the International Dunhuang Project in 1994. This ambitious program to conserve and digitize Dunhuang-related materials has made them available worldwide to experts and schoolchildren alike.

The project has established centers in institutions in China, France, Germany, Japan, Korea and other countries where Dunhuang materials are located. Not every institution that has Dunhuang documents has a center – the National Library of China, for example, has a center that conserves and digitizes materials for all of China except the Dunhuang area, which has its own center at the Dunhuang Research Academy to handle materials from Gansu Province, where Dunhuang and related sites are located.

In the centers, conservators and technicians assess documents that institutions in their areas hold to determine if they need conservation. State-of-the-art conservation methods are used to stabilize and repair documents so that they can safely be photographed. The goal of preservation and conservation measures is to stabilize and extend the lifespan of the artifacts using minimum intervention and a combination of safe, recognized modern techniques and traditional Asian methods and materials. The project also works to formulate and disseminate a conservation code of ethics, effective conservation approaches and common standards for conserving Asian materials among the participating institutions.

This 9th-10th century Amitabha Sutra is about a savior Buddha, a strain of Buddhism which later led to the Pure Land movement which has many Buddhist followers today. This scroll, in the British Library, illustrates some of the challenges that conservators face in preserving the fragile manuscripts. Many are much more damaged than this one - with only fragments surviving.

Catalogue records of each item's condition and conservation measures are made, along with any other information about its history, translations of it if there are any, and other information that a researcher would need. When conservation is complete, the items are carefully photographed to produce high quality images that are added with the catalogue information to the on-line archive. They then are returned to storage, sometimes after rehousing them in archival boxes. Each center maintains its own database along with a version of the project’s website in its main language. The local databases are synchronized with the main database so that the entire system is always up-to-date. Scholars are encouraged to submit their own catalogue entries and research results about individual items to the database.

Where writing has faded badly, infrared photography is used to make the writing visible. High-quality photography enables scholars to see details that would be difficult to see with the human eye alone.

Because conservation, photography and record keeping are handled in one workflow, fragile documents don’t have to be handled multiple times. Only lighting that doesn’t generate heat is used and the documents are photographed on cradles and other supports to prevent stress on them. Special supports are created for unusually shaped items.

The on-line database has replaced or is linked to other on- and off-line catalogues and has added functionality that previous tools didn’t have.

None of the participating institutions had the resources to give scholars full access to their collections, but by joining resources and knowledge they can allow scholars that access through the database. The project also has enabled institutions to get more funding for this purpose.

The project has opened a number of new research areas. Scholarship on the history of Chan (or Zen) Buddhism has been revolutionized and Tibetan Buddhist studies have developed and changed. In one dramatic example, Jacob Dalton of the University of California at Berkeley pieced together images of leaves of a manuscript that were divided among several libraries to find that the manuscript contains an early manual for performing human sacrifice.

Beijing University historians have used the digitized materials to chart ways in which foreign influence, especially that of Persia, shaped China.

Most Dunhuang studies are in history and religious studies, but some have been on the study of the fragile materials – paper, textiles, wood, ink and paint - that the original manuscripts are made from. The project has supported studies analyzing paper, ink, pigments and textiles and organizes regular conferences on conservation.

Many of the manuscripts are paper, which was invented in China in the 2nd or 1st centuries BCE and then spread westward along the trade routes. Ancient paper was made from cotton, hemp, linen, rice, bamboo and mulberry and was more durable than modern papers, so some paper documents from the region are in excellent condition.

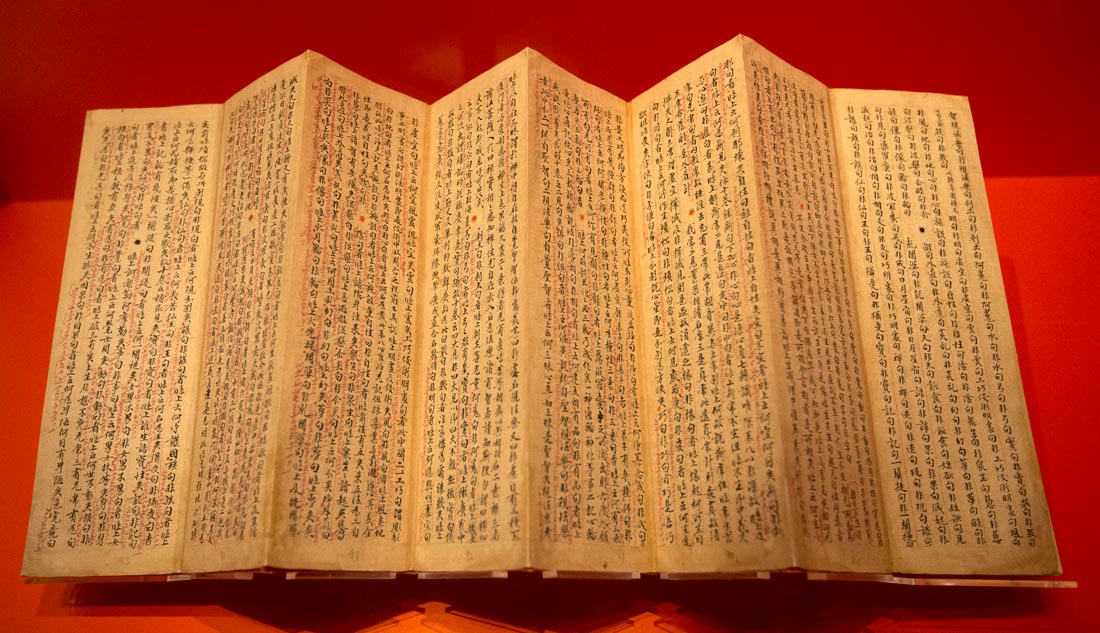

This concertina book is from a translators' workshop at Dunhuang. The black characters running vertically down the page are Chinese. The red ones in between are the Tibetan translation. The text is an important Chan (Zen) Buddhist text. The document, now in the British Library, is from the 9th-10th century.

Researchers can determine the composition of the paper to understand an object’s history, origin and age. The International Dunhuang Project is building a database of Asian historic paper fibers. Part of that research is aimed at avoiding the degradation of ancient paper from temperatures and humidity, light, infestation, poor handling, inappropriate conservation treatments and other extreme conditions. The conservation of paper items includes removing previous damaging conservation measures, surface cleaning, creating proper environmental conditions, filling in gaps where material has been lost, repairing tears and edges, flattening, adding end panels and providing acid free rollers to support scrolls and acid free standard boxes for storage.

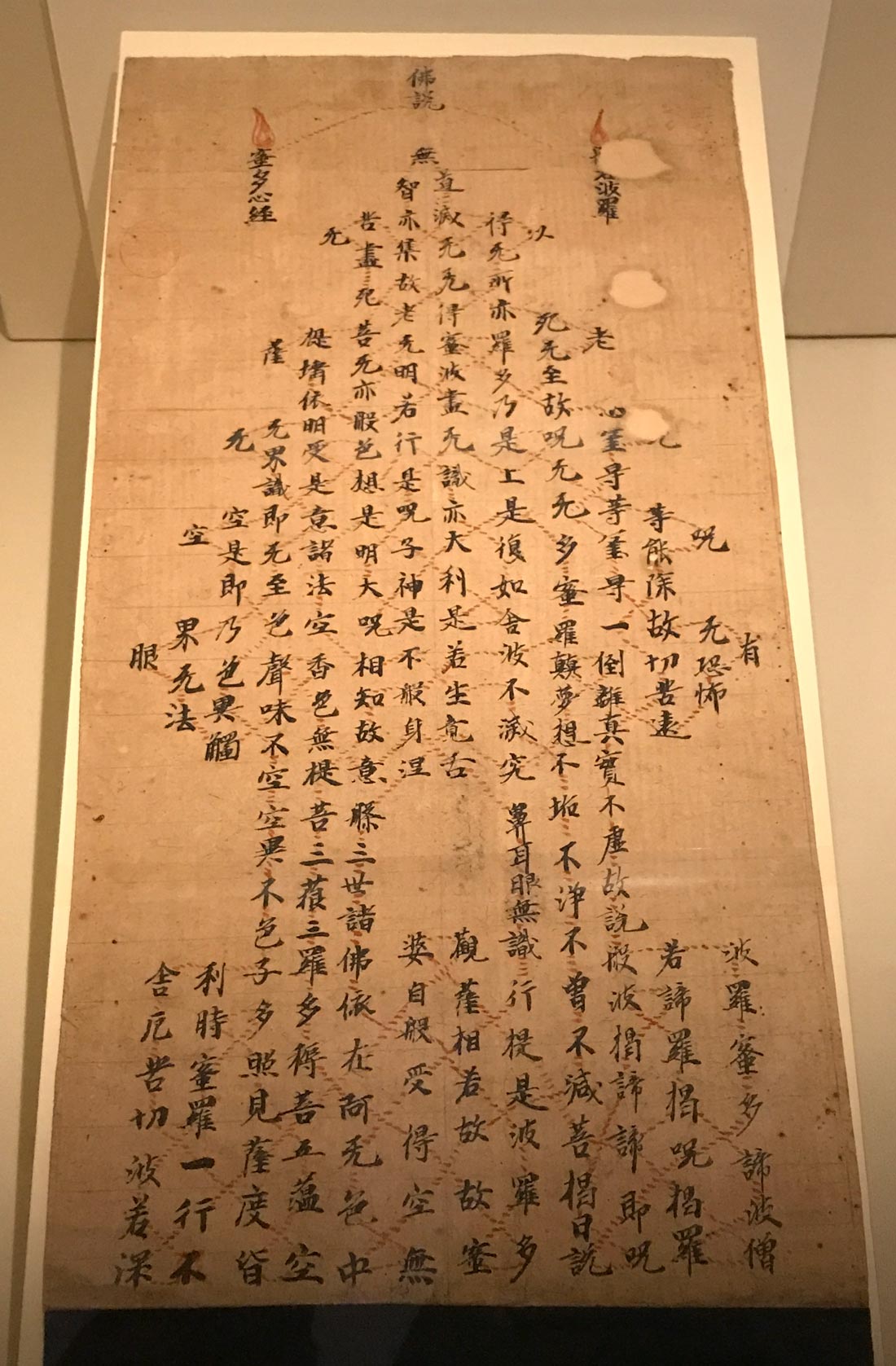

This Sutra of the Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom, now at the British Library, was written in a form that resembled a five-storey stupa. Stupas are Buddhist monuments used to house sacred relics.

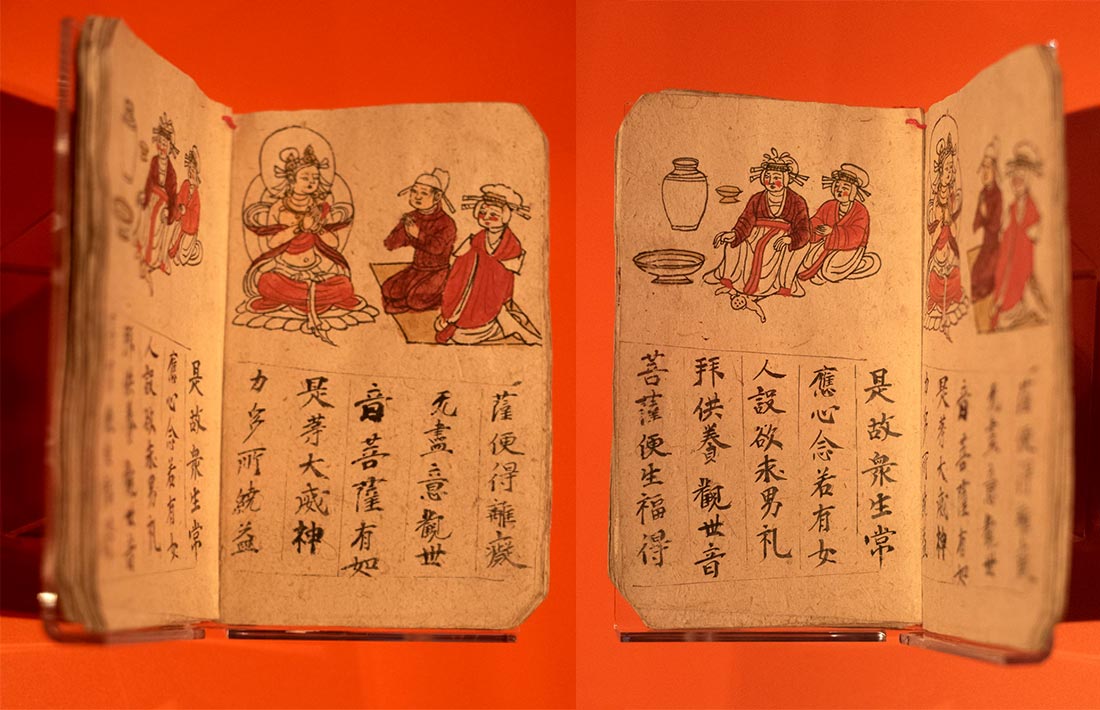

This small illustrated book is an amulet. Ancient Chinese books were read right to left, so the right side of the book shows a couple praying to the bodhisatva Guanyin for help in having a child. The left side of the book shows the wife giving birth to a child in fulfillment of the prayer. This c. 10th century book has a contemporary feel, as couples in modern Asia still appeal to Guanyin for help in producing a child.

Conservation and cataloguing of the Dunhuang artifacts is challenging because there is a wide variety of items. This ritual implement from the 9th or 10th century is one of the earliest known Tibetan painted works. Its exact ritual purpose is not clear.

Another major area of conservation is textiles that have been preserved in the desert conditions in eastern Central Asia. They need to be conserved and stored in a way that allows scholars to obtain information on their materials, weaves and pigments.

This is a painted end piece that was once attached to a scroll. It depicts two sacred hamsa birds associated with wisdom. This item is at the British Library.

Among the Dunhuang collections are objects made from stone, metal, glass, ceramics, plants, animals and synthetic materials, stucco, clay and wood. They must be examined, photographed and documented before conservation. The most common treatment is surface cleaning with a soft brush or special vacuum cleaner. Ingrained dirt is cleaned using cotton swabs and solvents or a poultice that removes stains and dirt. Sometimes damaged paint layers are stabilized and broken or cracked objects are repaired.

The conservation of cave murals, which institutions in a number of countries have, has become an international cooperative effort.

The project also organizes exhibitions and educational events. A exhibit on the Silk Road at the British Library in 2004 attracted 155,000 visitors, the most ever at an exhibit at the library. The library currently has a major exhibit on Buddhism which includes Dunhuang documents and paintings. Last year, participating institutions joined together to do a major exhibit on Tibetan history.

The British Library, British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum in London; the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin, Ireland; The National Library of China in Beijing and Dunhuang Academy in Dunhuang: the Academia Sinica in Taiwan; the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in Russia; the National Museum of India in New Delhi; Ryukoku University in Kyoto, Japan; the State Library and Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Berlin; the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and the Musee Guimet in Paris; the National Museum of Ethnography and the Sven Heden Foundation in Stockholm; the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington; The University of California, Princeton University, Morgan Library; the Research Institute of Korean Studies, Korea University, Seoul, South Korea; and the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen are among participants in the project. Other institutions also contribute digitized materials and cooperate with the project on exhibits and other events.

The locations of the participating institutions indicate the extent to which the Dunhuang documents were dispersed. Items collected by Aurel Stein, for example, are at several institutions. Some of the material he collected, including murals, paintings, artifacts and manuscripts, ended up in India because the Indian government sponsored his first three expeditions. Most of this material is at the National Museum of India in New Delhi, with a small amount in museums in Calcutta and Pakistan. The rest of the material he collected is shared between the British Library, British Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The British Library has thousands of paper, wood and textile items in addition to 10,000 photographs, negatives and lantern slides taken by Stein. The British Museum holds more than 1,500 archaeological artifacts Stein collected, as well as 240 paintings on silk and paper, 200 textiles, about 300 woodblock prints, and 4,000 coins. The Victoria and Albert Museum has more than 650 textiles he collected. The Bodleian Library at Oxford University has many of Stein’s personal papers and diaries.

The International Dunhuang Project has organized a Stein Site database based on Stein’s three books describing his expeditions. For some of those sites, Stein’s work remains the main source of information. Sometimes, he stated opinions that have since been refuted. To deal with this problem, other research on some sites is included in this database.

Another endeavor included conserving Chinese copies of the Lotus Sutra from Stein’s collection at the British Library. The sutra dates from between the first century BCE and the second century CE. It is important to Buddhists because it is thought to contain the Buddha’s final teaching, which is sufficient for salvation. It delivers the message that all sentient beings have the potential to obtain Buddhahood. The sutra is one of the most influential scriptures in Mahayana Buddhism and is highly regarded in a number of Asian countries, including China, Korea and Japan.

There are many versions of the sutra and images inspired by it can be seen in murals in the Mogao caves. An estimated 4,000 copies of the Lotus Sutra from Dunhuang are in institutions in Beijing, Paris, St. Petersburg and London. More than 1,000 copies are in Stein’s collection, some scrolls measuring up to 13 meters long. Nearly 800 copies of the sutra in Chinese were chosen to be conserved and digitized.

Stein is an unpopular figure in China because many Chinese believe he robbed China of priceless heritage items. The Chinese government has not formally requested the return of the Dunhuang items and Chinese government institutions are active collaborators with the British Library and other foreign institutions in the International Dunhuang Project and related research endeavors. Some Chinese scholars privately believe that it is advantageous to leave the documents in other countries because of the international interest in Dunhuang-related research that they generate. The International Dunhuang Project has acted as a safety valve to diffuse anger over Stein and other foreigners’ exportation of the documents because it has redirected attention from ownership of the originals to the cooperative effort to preserve them. It has been an inspiration for other cross-cultural, multidimensional library-related websites.

The project lends itself to international cooperation because it is the study of a major ancient trade route in which not just goods, but also ideas, knowledge, technologies, religions, cultures and arts from many lands were transferred and mingled. It is the largest project of its kind and more data is added to it daily. The size and scope of the collections, as well as their fragility and limited access, has meant that many of the manuscripts have yet to be studied in detail.

Other collections besides Stein’s that are part of the project include:

The Hoernle Collection of Central Asian manuscripts collected by the Indian government and sent to Augustus Hoernie in Calcutta, India, between 1895-1899. They are at the British Library.

The Pelliot Collection collected by Paul Pelliot in 1906-1908, at the Bibliotheque nationale de France.

The Kozlov Collection has thousands of manuscripts and woodblock prints collected by Pyotr Kozlov in the abandoned Tangut fortress city of Khara-Khoto in 1907-1909. They are at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in St Petersburg, Russia. He also collected about 600 manuscripts and printed books in Chinese, mostly Buddhist texts. Aurel Stein excavated the same site in 1917 and recovered several thousand Tangut manuscript fragments that are in the British Library.

The Oldenburg Collection was found by Sergey Oldenberg at sites around Turpan and Dunhuang. The Institute of Oriental Manuscripts and the Hermitage Museum in Russia hold his collection along with manuscripts collected by Sergey Malov in Khotan in 1909–1910, and Uighur manuscripts collected by N. N. Krotkov, the Russian consul in Urumqi and Ghulja. The Hermitage Museum holds Buddhist banners, paintings, murals, textiles, manuscript fragments, and Oldenburg's personal papers, diaries, maps and photographs about his expeditions.

The National Library of China has not only the Dunhuang documents that were not taken from China, but more than 7,000 items that it has since purchased or acquired by donation.

The Ōtani Collections were acquired by Otani Kozui, a Buddhist abbot from Kyoto, Japan. He collected mummies, grave goods, funerary texts, manuscripts, woodslips, murals, sculptures, textiles, coins and seals that are in libraries, museums and collections across Japan, Korea and China.

The Berlin Turpan Collections hold manuscript and woodblock fragments collected between 1902-1914 by Albert Grunwedel and Albert von le Coq. The items are at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities and the Oriental Department of the Berlin State Library.

Little was known about the heritage of the Silk Road until the explorers’ work.

After the scrolls were removed from Mogao, the complex experienced its own dramatic 20th century history. Dunhuang has the world’s largest, best preserved collection of Buddhist relics dating from the 5th-13th centuries. The site’s surviving 735 caves contain 45,000 square meters of murals and more than 2,000 sculptures. Statues from the early Tang period (618-718) depict sumptuously dressed figures such as the Chinese emperor, in rich colors. After the Tang, clans commissioned portraits in which women are in elaborate necklaces and gowns. Some caves have scenes of daily life – winnowing of wheat, people bathing, wedding preparations, commercial life. Some have painted patterns that make them look like tents. Others have sculpture niches. Some sculptures are huge – a 75-foot-long Buddha is carved from the rock face and a 50-foot-long dead Buddha is surrounded by paintings of mourning disciples. The murals document the life, trade, and changing styles of Buddhist art and the development of a distinct Dunhuang style incorporating Chinese, Central Asian and Indian elements.

The site was neglected until the 1940s, when the Dunhuang Research Academy began efforts to protect it from erosion and collapse. Chinese archaeologist Fan Jinshi spent more than 50 years protecting the Dunhuang caves from erosion, overtourism and political campaigns. During the disastrous 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, Fan and her colleagues sealed the caves to protect them from the Red Guards. However, when they showed up, they were not hostile and the caves remained intact. Fan, however, came under official condemnation for mourning her father, who committed suicide after being humiliated and interrogated.

Fan initiated the effort to work with the British Library on digitizing Dunhuang items. In recent years, the site’s main threat has been from overtourism. Fan led an effort to acquire advanced conservation and management skills from abroad that have helped with site planning, research, environmental controls in the caves and visitor management. Chinese scholars since have applied these methods to conserve other historical sites.

The contents of many of the caves and murals have been photographed for the International Dunhuang Project. Digitization has enabled exhibitions in which the caves and sculptures have been replicated along with musical instruments and garments depicted in cave paintings to teach visitors about the lifestyle of ancient peoples in Dunhuang. The exhibits have added importance because only a few caves are open to the public because of the risk of damage to them caused by light, weather and visitors breathing out carbon dioxide as they tour them.

Exhibitions including virtual reality can enable people to see parts of the caves that they couldn’t otherwise see. This year, when major tourist sites closed because of the coronavirus, the Mogao Grottos was among top historical sites that rolled out on-line virtual tours.

Japanese researchers have been working to clone statues and murals at more than 100 Dunhuang caves and repairing statues that were poorly touched up by amateurs in past centuries. The aim is to create an exhibition that will show the caves’ splendor more than a millennium ago. The project is copying 138 grottos to be placed in a tourism center in Dunhuang. Its goal is for visitors to quickly tour a few actual caves, and then look closely at the cloned ones. The copies are being made using historical documents and other materials as references.

The technology has been applied to Cave 57, which has a magnificent Tang Dynasty mural. Six of the Buddhist statues in the cave were inexpertly repaired about 200 years ago. The Japanese experts and the academy’s scholars have created two clay statues based on other Tang dynasty figures using a 3-D scanner and robotic technology. Tang-style coloring was applied to them to recreate the original statues’ appearance.

Among other Dunhuang projects is the digitization of 2,500 black and white photos taken by James and Lucy Lo in the caves in 1943-44 so they can be researched. These photographs preserved views of paintings and sculptures that now are damaged or no longer exist.

The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London also has built and exhibited a replica of one of the caves, and hosted art courses on cave mural techniques and making pigments by grinding mineral rocks.

In general, the international Dunhuang cooperation has been lauded, but some scholars are uneasy about aspects of it as China has invoked the history of the Silk Road in its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative to develop the countries and transcontinental infrastructure to its west. The Silk Road label for the east-west land routes was coined not by a historian but by a German geologist surveying routes for a transcontinental rail line to carry coal from China to Germany in 1877. Other scholars built on this theme, and it became an exotic narrative in the public imagination, centering around the ideas of peaceful international exchange, economic enrichment and openness.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, China and the Central Asian republics branded the area as a Silk Road crossroads between Europe and Asia, a notion which has its roots in the interpretation of the manuscripts and artifacts collected by the early European explorers in Central Asia. Not just China, but Japan, South Korea, and the United States all have formulated foreign policy around variations of a “new” Silk Road, although China is the leader.

The Silk Road has enabled Beijing to frame its foreign policy ambitions as peaceful and harmonious while expanding its influence in the countries to the west. China provides funds and expertise in maritime and land-based archaeology and conservation of historically significant landscapes and cities in Central Asia as the regionis is experiencing a boom in interest in its heritage. Central Asian countries are cooperating in international partnerships to preserve, manage and develop the material culture of the Silk Road. Such cooperation sometimes accompanies developmental and economic aid in other sectors.

However, some scholars worry that depicting Central Asia as the crossroads between Europe and Asia suggests that the area is merely a bridge between two more historically significant regions. China depicts its ethnic minorities as subsumed into the diversity that makes up the Chinese nation. The idea of the Silk Road also is connected with the spread of Buddhism, which raises the question of whether Silk Road cultural routes such as Mogao will serve to diminish the cultural influence of the Muslim minority groups in western China whose culture, language, and religious practices are already under threat. Some are concerned that the Silk Road narrative will result in other Central Asian traditions receiving less attention than they deserve as a result.

Check out these related items

Britain and Greece’s Parthenon Dispute

What are the chances that two men from one family set off international disputes by carting off treasures from Greece and China?

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

Tiananmen Square

China's Oct. 1 celebration of 70 years of Communist rule centers on Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s most controversial places.

Islam in China

Muslims in China are a diverse religious and cultural group with a tumultuous history who take various sides in political disputes.

China’s Export Porcelain

Chinese porcelain is durable and branded with its history, so it is used to trace China’s trade and cultural ties with other nations.