Inside a Chinese Painting

Photos by Forrest Anderson

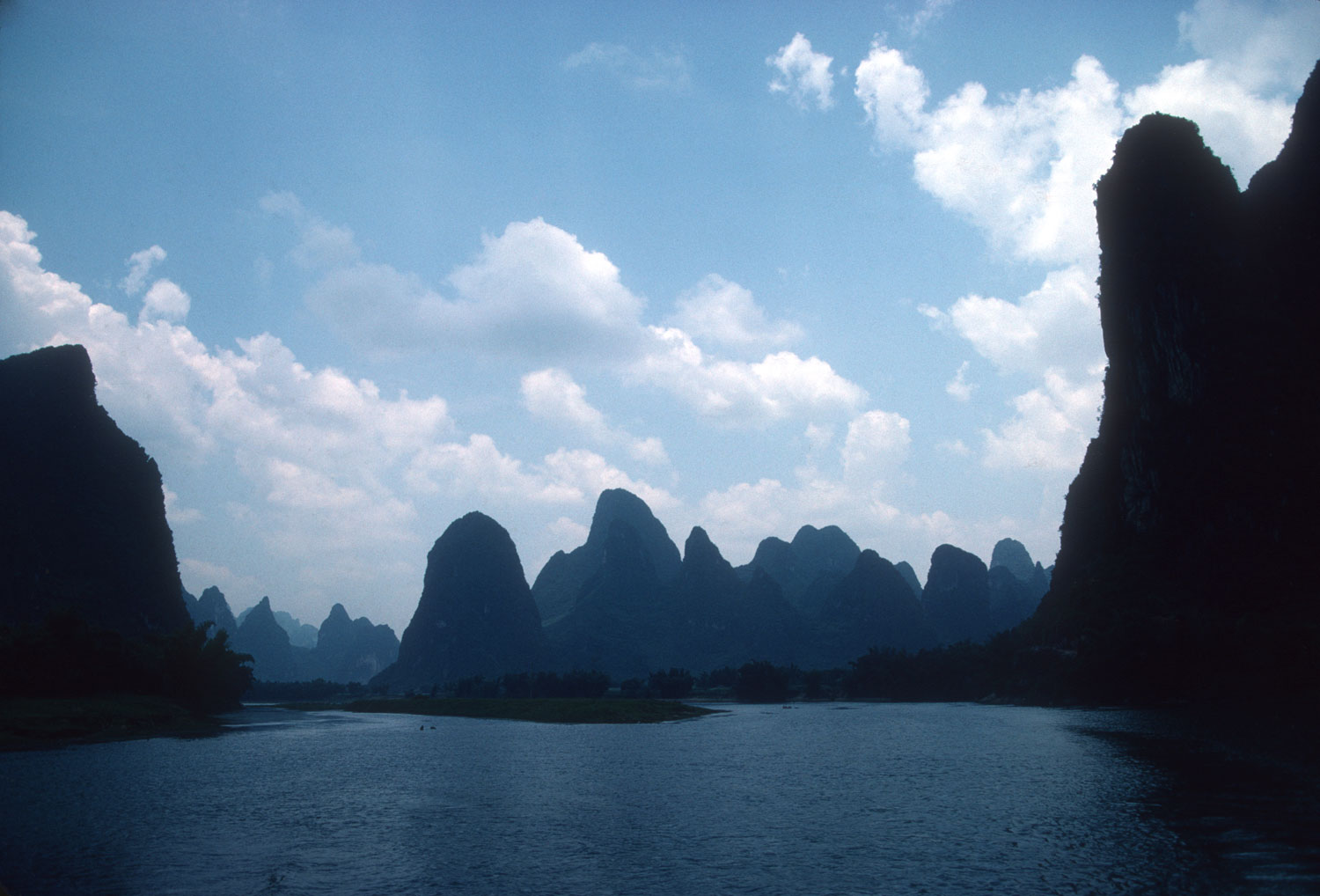

This blog began with the notion of an imaginary leisurely boat trip down a river on a sultry August day. I chose one of the most beautiful river trips in the world – through the magical land of steep hills and emerald rice paddies in Guilin, China.

We fortunately happen to have legacy photos of an actual August trip we once took down the Li River at Guilin. These photos, from a simpler time when many people in the Guilin area still followed the age-old rhythms of the river and the rice-growing season, are like stepping into a traditional Chinese landscape painting.

Guilin's superb scenery has made it the iconic cliché of Chinese landscape painting for centuries. The bucolic scenes of gumdrop hills, rice paddies stretching across the plain, water buffalo in the river and fishermen on bamboo rafts that characterize Guilin and that appear in these photographs have deep meaning in Chinese culture and history. It is such scenes that made old Guilin a beloved microcosm of China's culture.

Mountains (shan) and water (shui), the two features that give Chinese landscape its name of shanshui, define Guilin.

The Karst Landscape

Guilin’s central claim to fame is its karst topography. Guilin is the central jewel in one of the globe's largest karst regions, which stretches over four Chinese provinces. This dramatic topography was formed from the dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite and gypsum over tens of millions of years.

Long ago, Guilin was 200 meters under a sea in which 2,000-pound, 12-foot-long ichthyosaurs swam along at 24 miles per hour, and 10-foot-long nothosaurs foraged for fish.

When the tectonic plate that India was riding on collided with the Asian plate, creating the Himalayas, the impact caused Guilin to rise from the water. This exposed its flat plain to wind and annual monsoon rains, and the land began to erode way in acidic water. Cracks in the bedrock eventually widened. The soft rock eroded evenly so it stayed flat. Harder rock eroded more slowly, so patches of it began to rise over the plain and were sculpted into the limestone peaks that rise over Guilin today. In the limestone was captured the shells and skeletons of marine animals, including ichthyosaurs and nothosaurs. Eventually, more rock dissolved than remained, leaving the plain punctuated with the tall pinnacles that give Guilin its extraordinary appearance. Add the area’s two rivers and four lakes and you have the ingredients for phenomenal scenery.

The result is a rock climber’s dream, with peaks varying from beginner level to some of the world’s most difficult. Guilin is the top area for rock climbing in China.

Above, steep karst hills rise over the flat plain.

Karst formations come in tower, pinnacle and cone shapes, with bridges, gorges and large caves. Much of the Guilin Karst is protected in a national park and has natural vegetation, increasing the aesthetic value of the landscape. Because the area is home to a number of minority groups, part of the park management includes allowing minority groups to continue to harvest bamboo in the area.

Two types of karst landscapes predominate in Guilin - fenglin, which refers to peaks isolated from each other on flat plains, and fengcong, or linked peaks.

Karst evolution followed roughly the following path – the exposed flat plain began to develop depressions around points where water drained into underground cave passages. As these depressions or sinkholes grew, they combined to remove the remnants of the flat surface. Between them, conical hills called fengcong developed. This stage is called egg-box typography.

The depressions deepened with erosion until a base level was reached in the underlying rock. The depressions began to fill as erosion continued, until the landscape was a series of conical hills interspersed with flat plains. Then the bases of the cones eroded, making them morph from cones into steep towers, or fenglin karst. Soil eroded into the depressions and made flat plains. This type of karst has isolated hills rising from a limestone plain with a thin cover of alluvium.

Some of China's fengcong evolved down a parallel track that did not lead to fenglin. Fenglin are largely restricted to the more stable lowlands. In other locations, fengcong evolved through the first stages and then continued to grow under more rapid tectonic uplift and repeated rejuvenation that is different than that in Guilin.

Within the Guilin‐Yangshuo karst, small areas of fenglin and fengcong are so intertwined that there must have been parallel evolution of the two systems in one tectonic environment. Many fenglin areas are associated with sediment fans of rivers derived from adjacent hills. The Li River has entrenched a gorge through the finest of the fengcong karst.

The fantastic vertical crags of many Chinese paintings are realistic representations of Guilin’s spectacular scenery. In Guilin, the fenglin are surrounded by rice paddies on the alluvial plain.

Fenglin can only exist in areas that have a perfect environmental combination of pure, compact and strong limestone that allows the surface to be eroded off without reaching the base, an alluvium veneer overlying the bedrock limestone on the plain, a stable karst water table at the level of the karst plain and major inflows of water and sediment that can recharge and maintain the alluvial plain. There also must be a slow tectonic uplift that matches the surface erosion and maintains the karst plain as it gradually lowers through the limestone.

The Guangxi region where Guilin is located is separated by the Nan Mountains from China’s center and heart, the Yangtze River basin. As a result, Guangxi developed a distinct culture in ancient times. However, the Chinese Qin dynasty conquered Guangxi in the 2nd century BCE and set up the first administrative unit in Guilin, a county seat, in the 1st century BCE. The same dynasty then dug the Ling Canal between the headwaters of the Xiang River and the Li River, which is a tributary of the Gui River that leads eventually to Guangzhou in southern China. The result was that small boats from the Yangtze River could pass between the Yangtze to the north and the Xi river system to the south, thus linking central and southern China. Guilin participated in this system and canal and riverside trade grew up. Guilin became an important trade and cultural center. Many monasteries were built there in the 7th century, and Buddhist carvings from the time can still be seen at Fubo Hill in Guilin. Artists painted Guilin and poets wrote poems about its beauty.

The Thousand Buddhas Cave in Fubo Hill.

“The mountains are like jade hairpins,” wrote Tang poet Han Yu.

Some 1,500 years later, the central government posted a garrison at Guilin and developed the farmland. Guilin briefly was the provincial capital of Guangxi during China’s final imperial dynasty, the Qing (1644-1911/12). The city was destroyed during World War II, but then recovered and is today Guangxi’s third largest city. It has a variety of industries, but its status as a major tourist site has protected its air from the pollution that plagues many other Chinese cities.

The beautiful hills of Guilin have symbolic meaning in Chinese traditional art, as mountains in China have sacred significance as the site where heaven meets earth. They also are associated with the notion of perservance and the purifying experiences of Taoist mountain retreats.

The central feature of a visit to Guilin is a boat ride on the Li River past majestic karsts to the country town of Yangshuo. At the time we took this trip, water buffalo grazed on water plants in the shallow water, farmers worked in rice paddies, and fishermen floated by on bamboo rafts.

Fishermen

Fishermen of the Li River were descendents of people who worked on the river. They traditionally were surnamed Wang and came from a single village called Mao village or lived on the water in small houseboats. They caught fish to feed their families and sell in the markets. Tradition held that they came from a port on the South China Sea a thousand years ago.

They used a variety of ways to catch fish. Among them was using cormorants who were tethered on the fishermen's rafts with rings around their necks. At the fishermen’s command, they would jump off of the rafts and dive for fish. The rings constricted their necks so that they couldn’t swallow larger fish, so they disgorged them onto the bamboo decks of the rafts. The smaller fish could get through the ring and go down the cormorants’ throats.

Cormorant fishing is ancient, having been described by Japanese in a history of the Sui Dynasty of China that was completed in 636.

A man with his cormorants.

Cormorant fishing once was a successful industry but already was dying out when we first traveled to Guilin. Today it is primarily done as a demonstration for tourists. There are fewer fish in the Li River now than there once were and there are restrictions on fishing in the river in some locations.

The Li River fishermen also used several types of fishing nets depending on the depth and flow of the river and types of fish.

Spear fishing with a hand-held spear from land, shallow water or a boat has been done for millennia throughout the world, as early as paleolithic times. We saw spear fishing in Guilin, but it was not widespread.

China is a land of many waters which were used for millennia as the main transportation avenues, and fishing is associated with prosperity in the culture. Fish and fishermen are common symbolic motifs in Chinese art.

Boats and Bamboo rafts

Both wooden boats and bamboo rafts were used extensively on the river until recent years, when roads were built to villages so that people didn't have to travel on the water.

The traditional bamboo rafts of Guilin are flat bottomed basic water craft made of five bamboo poles lashed together. They were heavily used for fishing, transportation, hauling goods and recreation and were prominent in paintings of Guilin.

Bamboo is a good material for raft building because it is economical and grows abundantly. It is hollow and thus full of air, so it is buoyant.

Bamboo rafts are still one of the main ways to transport people, goods and cargo in many areas of the world, particularly Southeast Asia. Bamboo rafting is also a popular tourist activity.

Bamboo rafts were used as long ago as 3000 B.C. Researchers once assumed that people used crude bamboo rafts to make long-distance sea crossings to the islands of southeast Asia and Australia. However, a team from the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo, Japan, built a bamboo raft using stone tools, and a crew of five tried to sail it from Taiwan to the Ryukyu island chain in 2017 to test whether it could be done. They found that strong ocean currants made the raft unnavigable and and salt water damaged the bamboo. They now believe that such voyages would have taken sturdier boats.

Water buffalo

Among the most iconic figures in both Guilin and Chinese paintings are water buffalo. Some 95 percent of water buffalo are in Asia, although there are some in northern Africa and South America as well.

The southeast Asian variety are called swamp buffalo. They were domesticated in China some 4,000 years ago.

There are at least 170 million water buffaloes worldwide and more people depend on them for agricultural purposes than on any other animal. They are used for tilling food, milk products (their milk is richer in fat and protein than that of dairy cattle), leather and meat. In some Asian countries, their milk is the main source of dairy products. It makes particularly good cheese.

Swamp buffaloes are stocky, with large bellies, flat foreheads, prominent eyes and wide muzzles. They usually weigh 660-1200 pounds, but a few weigh more than 2,000 pounds. The calves are gray, but the adult turn dark slate colored.

Swamp buffaloes wallow in mudholes that they make with their horns, covering themselves with a thick coating of mud to regulate their temperature in hot climates.

They thrive on aquatic plants and graze while submerged. In some areas, they help control invasive plants by eating them. Water buffaloes also will eat hay, alfalfa, maize, oats, soybeans, sugarcane, turnips, citrus pulp, pineapple wastes and banana trimmings. They can continue to work well to the age of 30, and sometimes as old as 40.

Most water buffalo are owned by small farmers and are their most valuable capital asset as well as the most efficient and economical means to cultivate small fields. Children often tend them and ride them to wallows. Water buffalo, ideal for working in the deep mud of paddy fields, are called the “living tractor of the east.”

In rice-producing countries, they are used for threshing and transporting sheaves during the rice harvest. They provide power for oilseed mills, sugarcane presses, and water pumps. They are used as pack animals. Their dung is used as fertilizer. Their bones and horns are made into jewelry and musical instruments.

Many Asian farmers and their families have great affection for their water buffalo.

Wild water buffalo herds have been introduced into some wetlands to manage uncontrolled vegetation growth in and around them. They graze in clogged water and open it up for waterfowl and other wetland wildlife. However, when not controlled, they can trample vegetation, disturb bird and reptile nests and spread weeds.

Some Asian countries have cloned water buffalo in an effort to produce better buffalo calves.

The water buffalo has immense cultural significance in Southern Asia. In some countries, it is a zodiac animal. In Chinese tradition, it is symbolic of a contemplative life. It is associated with Taoism because of images of the Daoist sage Laozi riding a water buffalo.

Some ethnic groups in China and Indonesia sacrifice water buffalo at festivals, and a water buffalo head is a symbol of death in Tibet. Festivals that include racing and fighting water buffalo are held throughout Asia.

Today, water buffaloes are important in tourist demonstrations of local Guilin agriculture farm life.

Rice Growing

Rice is the world’s most important grain for human nutrition and caloric intake. It provides more than a fifth of the calories that humans consume worldwide. It is well suited to areas like Guilin with low labor costs and high rainfall, as it requires ample water and its cultivation is labor intensive.

The traditional method for cultivating rice is to flood fields while setting out young seedlings. This requires damming and channeling of water. This method reduces the growth of weeds and pests that don’t thrive in water.

Rice is the staple food of more than half the world's population and provides 20% of the world's dietary energy supply, more than wheat and more than corn.

Genetic studies indicate that all forms of Asian rice sprang from a single domestication event 13,500 to 8,200 years ago in China from a wild rice. Based on archaeological and linguistic evidence, this is believed to have occurred in the Yangtze River basin but there also are theories that rice domestication began around the central Pearl River valley in southern China or in Korea. Rice is believed to have arrived in India about 4,500 years ago and to have been hybridized with an undomesticated variety there. Rice cultivation spread throughout southern Asia and then beyond.

Populations in rice cultivating centers increased rapidly, with intensive rice cultivation in paddy fields. A southward migration of rice-farming cultures spread rice production to Southeast Asia.

China is the leading rice producing country, and Asian farmers in general produce 87 percent of the world’s rice production. India, Indonesia, Bangladesh and Vietnam also are major producers. Ninety-five percent of rice production is in developing countries, and most rice is cultivated by small farmers.

The single biggest problem with rice is preventable post-harvest farm losses such as poor transport, lack of proper storage and retail options. If these losses could be eliminated, another 70-100 million people in India alone could be fed.

Many countries consider rice a strategic food staple, and some governments subject the rice trade to a wide range of controls and interventions.

Rice cultivation has a significant impact on the environment, as its production is responsible for methane emissions and rice production uses a great deal of water. Global warming also has decreased the rice yield growth rate by 10-20 percent in some locations.

Researchers recently have found that putting a barley gene into rice creates a shift in biomass production from root to shoot, resulting in a 97 percent reduction in methane emissions. The modification also increases the amount of rice grains by 43%, which could make this method useful in feeding the growing world population.

The labor intensive nature of rice has been found to make Chinese communities that grow rice more interdependent, as compared to more independent cultures in wheat-growing communities.

Rice historically has been so important in Asian culture that many Asian countries have held ceremonial royal ploughing ceremonies to mark the beginning of rice planting.

Tourism is the major industry in Guilin today, with millions of people descending on the city annually to experience its scenery.

Check out these related items

Chinese Moments Published

Chinese Moments, our photo book on China in the turbulent 1980s and 1990s, has been published as an ebook and paperback.

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.

Islam in China

Muslims in China are a diverse religious and cultural group with a tumultuous history who take various sides in political disputes.