The Many Layers of Mona Lisa

Photos by Forrest Anderson

As the world prepares to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the May 2, 1519 death of Leonardo da Vinci, his most famous painting again is at the glaring center of this new spotlight on the master of the Renaissance.

So many layers of culture, history, philosophy and art criticism have been laid over this 30 x 20 7/8-inch painting since Leonardo painted it on a poplar panel that it is small wonder that many people who view it question what it really means.

The Mona Lisa is two paintings in one – a modest sized portrait of a serene young Italian woman with an expansive landscape painting behind her. The painting is a minimalist’s dream – its single figure is dressed well but not elaborately with no traditional symbols such as lilies or bowls of fruit or other props. She wears no visible jewelry. The scene behind her is a natural landscape with only a winding path and a bridge as evidence of humans. The painting appears to have no religious meaning. It is simply a masterfully done portrait.

And yet the Mona Lisa has become a major industry as an estimated six million people each year make pilgrimages to the Louvre in Paris to view it. Hanging in a bullet-proof case with a barrier in front that makes it almost impossible to see it clearly, the painting seems to possess a kind of spiritual quality. Large but respectful crowds push up to the barrier waiting to arrive at a point where they can take pictures of it or selfies of themselves with it. The contrast between the crowds and Mona Lisa’s calm, detached and slightly amused gaze as she looks out over the crowd makes for a surreal experience. Museum officials say many people who view the painting have little interest in seeing anything else in the museum or even the same room, despite the fact that on the other side of the free-standing wall upon which the Mona Lisa hangs are superb Titians.

A young woman in a crowd at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France, photographs the Mona Lisa on her smartphone. The painting is in a bulletproof case and unlike other treasures at the museum has two barriers in front of it that prevent people from getting close to it. The security measures are the result of its history of theft and vandalism.

A photograph taken on a smart phone of the painting allows one to see it more clearly than is possible from the distance at which it can be seen.

The painting, reproductions of which are plastered on banners and souvenirs around Paris, is hugely important to the Louvre Museum’s bottom line. Every 10,000 visitors to the museum creates 8.2 jobs in Paris’s economy, most of them related to hotel and restaurant industries, a 2004 survey of museums in France indicated. The museum has more than 8 million visitors a year, the most of any museum, and the museum indicates that 90 percent come foremost to see the Mona Lisa.

The painting has become the symbol of the Louvre and an important icon of Paris. Here, the Mona Lisa can be seen on the covers of guides printed in a host of languages.

Why does this modest-sized painting have such a magical pull? The Louvre has five other paintings by Leonardo that don’t get anywhere near the same attention. The Mona Lisa’s power is nearly unique in that it draws so many people from outside the art world.

Understanding the Mona Lisa phenomenon requires peeling off the rich historical, cultural, artistic and philosophic layers that have added to the painting’s meaning over more than half a millennia.

The Mona Lisa’s Birthplace

The Mona Lisa is a product of Florence, the capital of the Italian region of Tuscany and the birthplace of the Renaissance. Florence was a wealthy medieval trade and finance center that became so influential that its dialect became the basis of standard Italian. It is even today considered one of the world’s most beautiful and fashionable cities. From the 14th-16th centuries, it was one of the world’s most important cities politically, economically and culturally. The florin, the city’s currency, financed the development of industry all over Europe. Florentine bankers financed English kings, the papacy and the Renaissance reconstruction of Rome.

The city was home to the Medici, one of Europe’s most important aristocracy families and patrons of the arts who commissioned works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Botticelli and others. Florence also was an important scientific center that helped drive the Age of Discovery. Florentine bankers financed Henry the Navigator and Portuguese explorers who opened the route around Africa to India and the Far East. Christopher Columbus used a Florentine map to sell his first voyage to America to the Spanish monarchs and to navigate. Mercator’s Projection is a refined version of the map. Florentine scientists pioneered the study of optics, ballistics, astronomy and anatomy there. The city also was a center of textile production and the birthplace of the modern fashion industry.

The underlying Renaissance ideology of humanism, the notion that man was the center of the universe and that human achievement in education, classical arts, literature and science should be emphasized took off in Florence in the 14th century. The Renaissance and its ideals spread quickly through Europe after the invention and use of the Gutenberg press in 1450.

Shaping the movement were its foremost figures - Leonardo Da Vinci, Michaelangelo, Raphael, Sandro Botticelli, Donatello, William Shakespeare, John Milton, William Tyndale, Titian, Niccolo Machiavelli, Dante, Giotto, Geoffrey Chaucer, Nicolaus Copernicus and Galileo among others. Art, architecture and science were closely linked in Florence. Artists explored anatomy to recreate the human body precisely and studied mathematics to design magnificent buildings.

The Artist

Leonardo da Vinci was an inventor, artist who drew, painted and sculpted, architect, scientist, musician, mathematician, engineer, writer and an expert in anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, history and cartography.

He epitomized the Renaissance humanist ideal and the Renaissance man, a person of great curiosity, inventiveness and a great diversity of talents. His prodigious talents have made him appear mysterious although his writings and drawings indicate that his mind was direct and logical.

Leonardo was born in Florence in 1452 and died in France in 1519 at age 67. He was apprenticed at age 14 to the then-foremost artist of Florence, Andrea de Cione, known as Verrochio. Leonardo trained with him for seven years. He learned drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics and woodworking in addition to drawing, painting, sculpting and modeling. At age 20, he qualified as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the guild of artists and doctors of medicine. Leonardo also worked in Milan, Rome, Bologna, Venice and finally France.

His most famous portrait is the Mona Lisa, while his The Last Supper is the most reproduced religious painting ever and his drawing of Vitruvian Man is one of the world’s most famous cultural icons. His painting Salvator Mundi sold for $450.03 million in New York in 2017, the highest price ever paid for a work of art. His work contributed heavily and continues today to contribute to the work of other artists as well as photographers.

Although his substantial discoveries in anatomy, engineering and other areas were recorded in the journals and notebooks he kept and they display an enormous range of interests and inquiries, they were not published for 200 years. He drew aging, emotions, facial deformities and signs of illness. He made studies of the anatomy of many animals and dissected and documented muscles, nerves and blood vessels to describe the physiology and mechanics of movement. He documented that the heart defined the circulatory system and was the first to define arterosclerosis and liver cirrhosis. He made models of the cerebral ventricles and constructed a glass aorta to observe the circulation of blood through the aortic valve. He designed architecture, defensive works and made studies on flight. A leading figure in his day, he remains so now as people flock to read books about him and attend exhibitions of his work. His notebooks have much more impact today than they did in his lifetime, as people in fields from medicine to aeronautics as well as artists study them for insights.

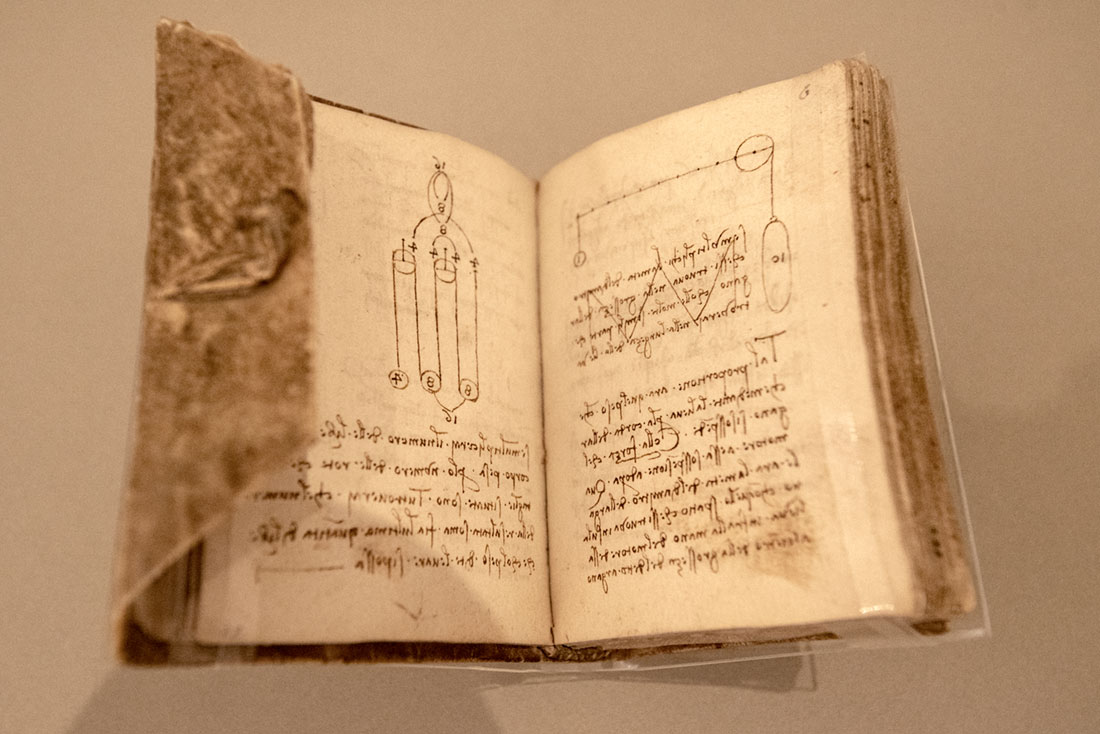

This small notebook of Leonardo's, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, shows his mirrored script.

He wrote in a mirrored cursive script, right to left, which has always been interesting to me as I did the same when I first learned to write. This phenomenon is limited to left-handed people. My grandmother, a school teacher, worked extensively with me to teach me to write normally. I remember how strange I thought it was that other people couldn’t read my mirrored writing, which seemed perfectly clear to me. Later in school, I sometimes wrote in mirrored script to annoy my teachers when they were looking over my shoulder as I was writing.

Leonardo set the tone for studies of perspective, shadow, light and human emotion to add realism, naturalism and what Renaissance artists regarded as universal human values to their work. Leonardo had absolute faith in a natural world that made sense and could be figured out, believing that he simply needed to find out its logic through his experiments and inquiries. It is these qualities of realism that Leonardo poured into the Mona Lisa and that contribute to the painting’s international appeal.

The Subject

Even as it portrays a serene woman sitting motionless, the painting seems to quietly challenge the then-ubiquitous stereotypes of women in art as the Virgin Mary, Eve or a fallen woman in a biblical or classical scene. Unlike those idealized images, the Mona Lisa looks exceptionally ordinary. This is especially true in France and Italy, where her appearance is almost a stereotype of the dark wavy hair, eyes and olive complexion that many women in France and Italy have. She looks like a version of someone you might meet on the subway in Paris and other Mediterranean cities today. She comes across as your sister or your friend.

That’s probably because it is likely that the model for the painting was an ordinary woman. Although a number of rich, famous women have been suggested as the model, most experts believe the painting is of Lisa Gherardini, who was born in 1479 in Florence. It is believed that her husband, a merchant who sold cloth and silk in Florence, commissioned the painting. Lisa was born into an old aristocratic family declining in fortune and influence, to her father’s third wife. His previous two wives had died in childbirth. Lisa became the eldest of seven children.

Lisa grew up in several locations in Florence, at one point living near Leonardo Da Vinci’s father, Ser Piero da Vinci. Her family owned farms where wheat, olives and fruits were grown, and she and her family spent the summers in a small country home in a village south of Florence so that her father could supervise the wheat harvest on lands he leased there. It was a comfortable middle-class life.

In 1495 when she was 15, Lisa became the third wife of the merchant Francesco de Bartolomeo di Zanobi del Giocondo, providing a modest dowry of money and a farm not far from land Michelangelo later owned. She brought her family’s status to the marriage and her husband supplied the income. They apparently lived with relatives for the first eight years until her husband built a house in Florence. Apparently to celebrate it and to celebrate the birth of her second son, her husband commissioned Leonardo to paint Lisa in 1503. Leonardo was by then 51. Lisa was 23.

By 1507, Lisa had five children and a baby daughter had died. She also raised the son of her husband’s first wife Camilla, who had been a year old when his mother died. Lisa and her husband named their second child Camilla. This Camilla and another daughter, Marietta, became Catholic nuns, but Camilla died at age 18.

Francesco became a Florence official who apparently supported the Medicis, as he was imprisoned and fined in 1512 when the Medici family was exiled. Francesco was released when the Medici returned to power.

Francesco’s 1537 will revealed his affection for Lisa: "Given the affection and love of the testator towards Mona Lisa, his beloved wife; in consideration of the fact that Lisa has always acted with a noble spirit and as a faithful wife; wishing that she shall have all she needs…"

Scholars say that Lisa’s hands in the painting, with the right hand resting over the left, portray her as a faithful wife. Lisa was simply but fashionably dressed in the portrait in Spanish-influenced fashion of the day.

The family never received the painting, however. Leonardo was not employed when he got the commission to paint the portrait, but he got a more valuable commission later the same year that apparently pushed the Mona Lisa to the side. It was still unfinished in 1506 and was never delivered to the merchant’s family. Instead, Leonardo took it with him anywhere he lived for the rest of his life, and may have finished it as much as a decade later in France.

At least seven other women besides Lisa had been considered possible subjects of the painting, with varying degrees of evidence and resemblance to the painting. However, a1503 marginal note in a 1477 printing of a volume by the Roman philosopher Cicero was discovered in 2005 at the University of Heidelberg. The note by Agosto Vespucci said that Leonardo was working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo. The Louvre’s position is that Leonardo painted in 1503 the portrait of a Florentine woman named Lisa del Giocondo, but the museum’s staff cannot be absolutely certain that she is the person in the Mona Lisa painting.

In 1550, an acquaintance of the family wrote that Leonardo had painted Mona Lisa for the merchant. The painting is also called La Gioconda in Italian and la Joconde, or the happy one, in French. The term Mona in the alternative title, Mona Lisa, is a contraction of Madonna, which means My Lady or Madame in Italian. The two pieces of written evidence linking the painting to Giocondo have led most historians to conclude that the portrait is of his wife, Lisa.

French King Francis 1 asked Leonardo to move to France in Leonardo’s later life and Leonardo died there in 1519. The personal papers of Leonardo’s assistant, Salai, said that he owned a portrait called La Gioconda that was bequeathed to him by Leonardo. French King Francis 1 acquired the painting and it went into the French royal collection. It became the property of the French government after the French Revolution.

The three-quarter pose used in Mona Lisa has since become a standard portraiture pose that still is used today in both paintings and portrait photography.

Mona Lisa’s smile probably is more a result of Leonardo’s skill than any particular secret that she held. Leonardo, like many other artists, dissected corpses but he went beyond them to become a real anatomist. He understood how the nerves and muscles in the face worked and also had dissected the eyes, done experiments involving vision and had figured out a great deal about how vision worked. Research in 2003 by Professor Margaret Livingstone of Harvard University indicated that Mona Lisa's smile disappears when observed with direct vision, which is known as foveal. The fovea is a tiny pit in the macula of the retina that provides the clearest, sharpest image. Direct vision is a central line of sight that connects an object to the fovea.

Leonardo understood that people see only a small part of any scene in sharp focus, with the rest somewhat blurred and he pioneered a technique of soft blending, or sfumato, to capitalize on this feature of human vision. He combined focus and blur and light and shadow to create focused areas in the painting, such as Lisa’s eyes, that draw attention. He blended and blurred other areas, including ones in shadow along the edges and the background to make the woman appear alive, as we would see each other. Allowing some areas to emerge from darkness into light created an illusion of depth and volume. Lisa’s hands emerge from blurred shadows and her face from her blurred hair and veil. the technique also left some parts of the picture to the imagination, drawing the viewer into the painting to participate mentally in its creation. He used this technique of blurring on the corners of her mouth and eyes to produce a figure that is astoundingly lifelike.

The portrait has similarities to many Renaissance depictions of the Virgin Mary, who was considered the epitome of womanhood, and to the women in another Leonardo painting in the French collection, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne. The expressions and features in the two paintings are similar, shadows and light are used in similar ways, and both have beautiful landscapes in the back. Both are believed to have been painted at roughly the same time. The Madonna was the feminine ideal of the time, and the content, modest smile on Mona Lisa’s face is similar to ones Leonardo and other painters placed on images of the Virgin Mary. Such a smile reflected a woman’s virtue, and it is possible that there is no more mystery behind the smile other than that convention.

Because the subject of the Mona Lisa is not outstandingly beautiful, it is believed that Leonardo painted her accurately although within this common feminine genre.

Both paintings had a significant influence on the work of other artists including Michelangelo, Raphael and others, who in turn influenced later artists.

The Mona Lisa also benefited from Leonardo’s endless tinkering with and revision of his projects. Examinations have revealed that the Mona Lisa was refined over time and originally more elaborately dressed with hairpins and a pearl headdress. Her expression and the direction of her gaze also were changed. She also had eyelashes and eyebrows that apparently were removed in an 1809 cleaning.

The Landscape

The landscape behind Lisa is one of the most beautiful parts of the painting. It is divided into two parts – a front part with a winding path and a bridge in warm colors, and a natural area in greens and blues behind and above it with water, rocks and hills. The horizon is on the same level as Lisa’s eyes, linking her with the landscape in the viewer’s focus. The two sides differ somewhat on either side of her head. The scene is reminiscent of parts of Tuscany, but the actual landscape has never been identified definitively. The landscape is unsystematic, with several possible vanishing points, contributing to what some critics call the mysterious look of the painting. The scene’s lighting gives it a feeling of twilight, which Leonardo also favored in other portraits.

Leonardo in his writings commented on the variations of color that occur in landscapes, with the more distant views appearing more blue. The rocks are similar to those in religious pictures Leonardo painted during the same period. The painting also has been found to have the unusual characteristic of adjusting to different lighting as a real object would.

The explanation for the landscape has turned out to be simpler than many experts had thought. The Louvre asked the conservators of the Museo National del Prado in Madrid, Spain, to lend them a copy of a similar painting called the La Gioconda for a special exhibition in 2012. In preparation, conservators inspected it using infrared light and found that its black background had a landscape underneath it. The black overpainting was removed, revealing a landscape that looked very much like the Mona Lisa landscape. It now is assumed that the two paintings were made at the same time in Leonardo’s studio, the Mona Lisa by Leonardo and the Madrid painting by a student of his, as the coordinates of the landmarks in the two paintings’ landscape backgrounds match 99.8 percent. The paintings show slightly different perspectives, which can be accounted for by the differing positions of Leonardo and the artist who did the other painting. The background in the Madrid painting is closer to where the artist would have been than is the one in the Mona Lisa. However, the two landscapes do not otherwise show major perspective differences as they would have done had they been created from a real scene. It seems clear that the landscape backgrounds were done from a backdrop in Leonardo’s studio.

The Timing

It is uncertain exactly when Leonardo finished the painting. One contemporary, Giorgio Vasari, said that Leonardo had lingered over it for four years and left it unfinished. Raphael, who visited Leonardo’s studio many times, made a pen and ink sketch around 1504 that is believed to be based on the portrait. However, the sketch had columns on the side. Some historians thought that the Mona Lisa originally had columns that were cut off, but testing has showed that it did not. Some believe Leonardo finished it in 1516-17 in France, as it is characteristic of his style after 1513.

It is also not 100 percent certain Lisa’s husband commissioned the painting, as Antonio de Beatis, after visiting with Leonardo in 1517, said that the painting was executed at the instance of Giuliano de Lorenzo de’ Medici. Some suggest that Leonardo actually painted two paintings, an earlier one with columns and the second without columns that was commissioned by Giuliano de’ Medici ca. 1513. This would be the one that is in the Louvre today.

After entering the French Royal Collection, the painting was at the French Palace of Fontainebleau until Louis the XIV moved it to Versailles. After the French Revolution, it was moved to the Louvre, but spent a brief time hanging in Napoleon’s bedroom at the Tuileries Palace before being moved back to the Louvre. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and during World War II, it was moved to other locations for safe keeping.

The painting grew in influence as Leonardo’s reputation as a genius spread during the 19th century, during which a Renaissance-style mix of art and science was greatly admired. The painting’s reputation for realism was somewhat obscured as it became fashionable to write about the Mona Lisa’s mysterious smile during the Victorian area and later. Theories about mysteries behind the painting overshadowed its more straightforward reality to a degree that might have been surprising to the artist and his subject.

20th Century Fame

The Mona Lisa was admired in the art world but not widely known generally until 1911, when three Italian employees of the Louvre hid in a closet and walked out with the painting in the early morning while the museum was still closed. They thought Napoleon had stolen the painting and it should be returned to Italy and displayed there. The heist wasn’t noticed for 28 hours, until an artist who was painting the gallery in which it had hung was irritated that it had been removed and inquired as to when it would be returned. He thought it had been taken to the roof to be photographed, as the cameras of the time were mainly used outdoors. When the photographers told an inquiring guard that they didn’t have the painting, a search for the thieves was on.

The heist was a national scandal, partly because many French already were mad because American millionaires were buying up some of the best paintings from France. Among famous suspects were French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who was arrested and imprisoned, Pablo Picasso, art lover and American tycoon J.P. Morgan, and the Kaiser of Germany. When the Louvre reopened a week after the robbery, patrons rushed to see the empty spot.

One of the thieves, Vincenzo Perugia, stashed the painting in the false bottom of a trunk at his Paris boardinghouse. When he tried to sell it 28 months later, the dealer he contacted asked the head of an Italian art gallery to go check it out. A stamp on the back confirmed its authenticity. Perugia was arrested and sentenced to eight months in prison. A few days later, World War I broke out, and the painting was bumped off the front pages of newspapers. However, the theft made it famous worldwide as a Renaissance masterpiece.

The painting became a popular draw, but also the object of several attacks. A man who claimed to be in love with it with cut it with a razor blade and tried to steal it, and someone threw a rock at it in 1956, shattering the glass covering it and chipping off a small speck of its left elbow. A woman sprayed it with red paint in 1974 in a protest against inadequate access for disabled people at the museum, and a Russian woman who had been denied French citizenship lobbed a teacup at it in 2009.

Each attack resulted in a higher level of security for the painting until it is no longer possible for museum patrons to approach it closely and examine it as they can other artworks in the Louvre.

Restoration and Care

The painting darkened over the years because of varnish applications. Its 1809 cleaning and revarnishing gave it a washed-out appearance.

The panel on which the painting was created has warped with changes in humidity and there is a crack from the top to the figure’s hairline. Sometime in the 18-19th centuries, two butterfly-shaped walnut braces were inserted into the back of the panel to stabilize the crack. The upper brace fell out in the late 19th or early 20th century, and a restorer replaced it.

The picture is kept under climate-controlled conditions – 50% ±10% in a case supplemented with a bed of silica gel that provides 55% constant relative humidity, as fluctuations in humidity are a primary cause of deterioration in artworks. The temperature is maintained at a constant moderate temperature within three degrees. The painting is no longer loaned to other museums because of its fragility.

The frame has been swapped out several times. In 1951, the painting got a flexible oak frame with beech crosspieces that exerted pressure on the panel to keep it from warping. They were found to be infested with insects in 1970 and were replaced with maple crosspieces. They were again replaced in 2004-5 with sycamore and an additional metal one that monitors the warp. The current frame is from the Renaissance and the picture was placed in it in 1909.

When the painting has needed retouching, the changes have been made with watercolors.

During the 20th century, the painting has been widely reproduced in hundreds of paintings and thousands of ads. It has been depicted smoking a pipe, with a moustache and goutee, with dark glasses, with Steve Jobs' nose, in psychedelic colors, pixelated, half-toned, cartooned and as a minion. Artists such as Salvador Dali created portraits of themselves as Mona Lisa. Mural versions have been painted on city walls in Paris, Tokyo, Berlin and other locations.

There also are a number of other Renaissance paintings similar to the Mona Lisa.

The Mona Lisa is one of France’s most well-known icons. She not only gets a steady stream of thousands of visitors daily but some send her flowers and messages to her own mailbox.

She belongs to the French public and cannot be bought or sold. Beloved worldwide, she is among the most compelling visual testaments to the universal human values of the Renaissance.

Check out these related items

What is the Louvre?

The former palace, the world's largest museum, music video and fashion show venue, and global brand has never been more cool.

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

Britain and Greece’s Parthenon Dispute

What are the chances that two men from one family set off international disputes by carting off treasures from Greece and China?

Portraits of Mary

Mary, the mother of Christ, may be the most prominent visual icon in the world. We explore her history.

Scaffolding the World

Finding a historical site shrouded in scaffolding is disappointing, but it is a valuable tool for preserving the world's heritage.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.