Why is Washington, D.C. so Roman?

Photos by Forrest Anderson

Washington, D.C. is separated from ancient Rome by an ocean, thousands of miles and about 1600 years, but Rome dominates Washington’s architectural character more than that of almost any major city.

A tour of Washington’s most prominent landmarks makes it clear that the American city was the product of a deliberate, concerted effort to emulate the capital of the Roman empire. Why would a new nation that had just thrown off the British Empire to establish a republic model its capital on a long-gone European empire?

The answer to this question is one of the most fascinating tales in American history. It also is contemporary because of a controversial executive order signed by former President Donald Trump to require perpetuation of the classic style in future federal buildings in Washington and federal courthouses nationwide. The order’s future is unknown under the current administration, but it illuminates the continuing influence of classical Roman architecture on American public buildings and monuments.

The Neoclassic Movement

That influence began decades before the American Revolution in Europe, as the neoclassical movement gathered steam in reaction to the ornate vanity, extravagance and autocracy of French King Louis XIV’s court. Americans were far from the only opponents of autocratic kings who lived in showy splendor on the labors of their subjects. The winds of political reform blew across Europe and into Asia as growing, modernizing countries reconsidered the basis on which they wanted to be governed. The Age of Enlightenment emphasized nature and simplicity that were the antitheses of elaborate royal courts, and the Industrial Revolution stressed efficiency, invention and science over hierarchy.

Discoveries of ancient Roman ruins such as Pompeii and Herculaneum in the same era sent explorers scurrying to those and other sites in search of ancient objects that aristocrats purchased to display in their homes. Some of these elite built new Roman-style houses. They stocked their libraries with books about the discoveries, many of which included drawings and etchings. Many went on Grand Tours of Italy, visiting museums, ancient sites and Renaissance museums as well as collecting antique souvenirs. These activities sparked an artistic and political movement called neoclassicism that came to dominate new architecture as architects interpreted ancient Roman architecture in their designs.

The first neoclassical structures in Italy were built in the 1730s, and the movement flourished in the second half of the century while the United States was being established. Because neoclassicism caught on all over Europe and the Americas, it was considered international.

It spread to fashion, with women wearing tunic-style clothing and Greek and Roman hair styles. Furniture influenced by ancient forms became fashionable, along with rooms with Roman-style relief sculptures, vases, marble sculptures and fireplaces topped with Roman-style temple fronts.

Scholars, archaeologists, architects, and political leaders looked to the Roman past to figure out what made a great civilization.

“There is but one way for the moderns to become great, and perhaps unequalled … by imitating the ancients,” wrote German historian Johann Winckelmann in his 1755 book, Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture.

Winckelmann’s History of the Art of Antiquity, published in 1764, was immensely influential in this movement to recreate a distant, lost ideal world of pastoralism with a white marble Greek temple. Ancient statesmen became larger than life heroes upon which statesmen of the 18th and 19th centuries modeled themselves.

The style became associated with the clamor for political reform as Greek and Roman motifs were repurposed to express the ideals of enlightened government, justice, and reforms. The movement produced one of the most prominent and iconic architectural styles of the Western world.

American Neoclassicism

Americans became obsessed with neoclassicism, as Rome at the time was the only example of a major republic in Western history. As they debated the form that their new republic would take, they shared Roman texts and ideas. Thomas Jefferson included Roman ideas of government in the Declaration of Independence. It was a government that drew on ancient models to reform politics, protect individuals, and constrain tyranny.

Americans positioned themselves in the tradition of ancient Greeks and Romans who had debated and developed principles of justice, rule of law, liberty, limited government, and due process.

Jefferson, an architect, greatly admired both Roman republican values and architecture, which to him epitomized the simplicity, grandeur, balance, and social ideals of the new nation. He modeled his designs for the Virginia State Capitol building on the Maison Carrée, a 1st-century BC Roman temple in France, and built his house, Monticello, in neoclassical style.

Jefferson became a key figure in linking new American ideals of government with ancient Roman visual concepts. The founding fathers detested the British monarchy, but they were far from turning their backs on the past. Instead, they believed that there were universal truths that could be discovered in the collective wisdom of antiquity and shaped for their own political goals. These ideas could lend cultural stability to the fledgling government.

Neoclassical architecture provided visual stability, grandeur and public spaces for the new ideas about government.

American neoclassicism influenced civics, art, design, and ideas from Jefferson’s era through the first half of the 20th century. The style permeated popular culture and education. In arts and government, neoclassicism incorporated order, simplicity, clarity, and reason. Classical stories, allusions and writings helped define American ethical, political, oratorical, artistic and educational ideals. Americans used classical examples as models and guides in a multitude of fields. Greco-Roman literature and philosophy were central to revolutionary political thought, education and cultural exchange.

The American interest in antiquity also encompassed the broader history of the ancient Mediterranean as archaeologists, 19th century scholars and visitors made Cleopatra, the pyramids, the Sphinx, mummies, and obelisks part of popular American culture.

Neoclassicism held that art should express ideal virtues and convey a civilizing and reforming moral message, making it an ideal form for public buildings aimed at propagating democratic ideals. The architecture, painting and sculpture adopted grand historical topics from the Bible, classical mythology, history and political themes.

Battles, processions, and other historical events were preferred topics of neoclassical paintings, with figures arranged in pyramidal groupings with lighted faces. Storm clouds, battlefield smoke and a sense of drama and sacrifice permeated these works.

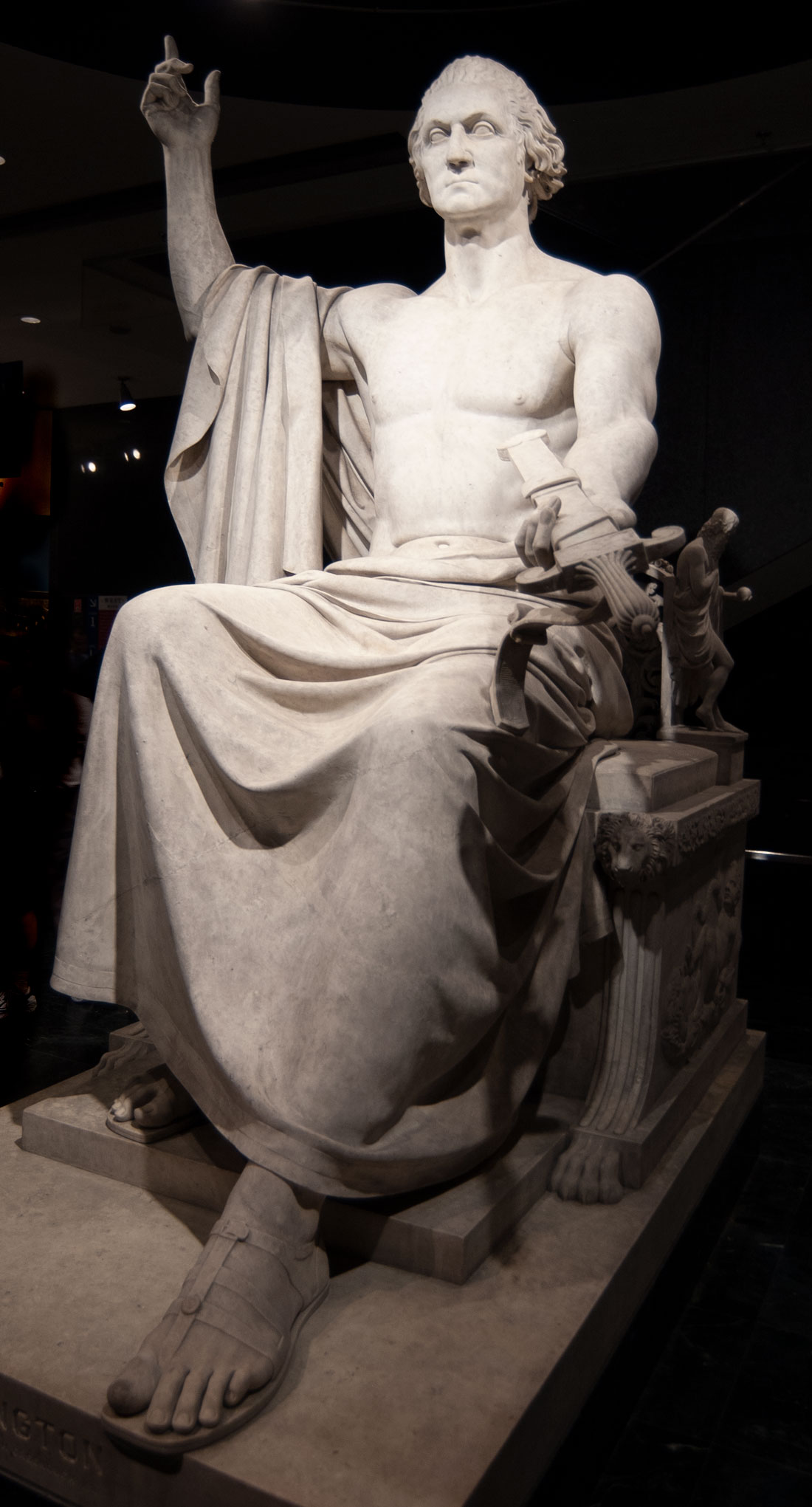

Sculptors of the neoclassical era portrayed George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and other founding fathers as models of truth, nature, simplicity and grace. These portraits were reproduced in textbooks, copies and on stamps and coins until they dominated the public perception of these men. They provided a visual pantheon of heroes to go along with the new political order.

Washington

Washington D.C. has more public buildings with classic Greek-Roman-style pediments than just about any major city. The Irish poet Thomas Moore called the city “Modern Rome.”

Roman city planning, with its emphasis on a central forum, main wide boulevards, occasional diagonal streets and order had a great influence on the planning of Washington and other major cities in the 18th and 19th centuries. St. Petersburg, Russia; Havana, Cuba; Barcelona, Spain; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Mexico City, Mexico, and even Athens, Greece, were reorganized according to neoclassical city plans.

Washington’s central landscape feature is the Mall connecting surrounding public buildings, museums and monuments. The Mall today is a site for important gatherings. At the opposite end of the mall from the Capitol is the Lincoln Memorial, built to resemble the Parthenon which is a symbol of democracy. The Washington Monument is in the middle of the Mall.

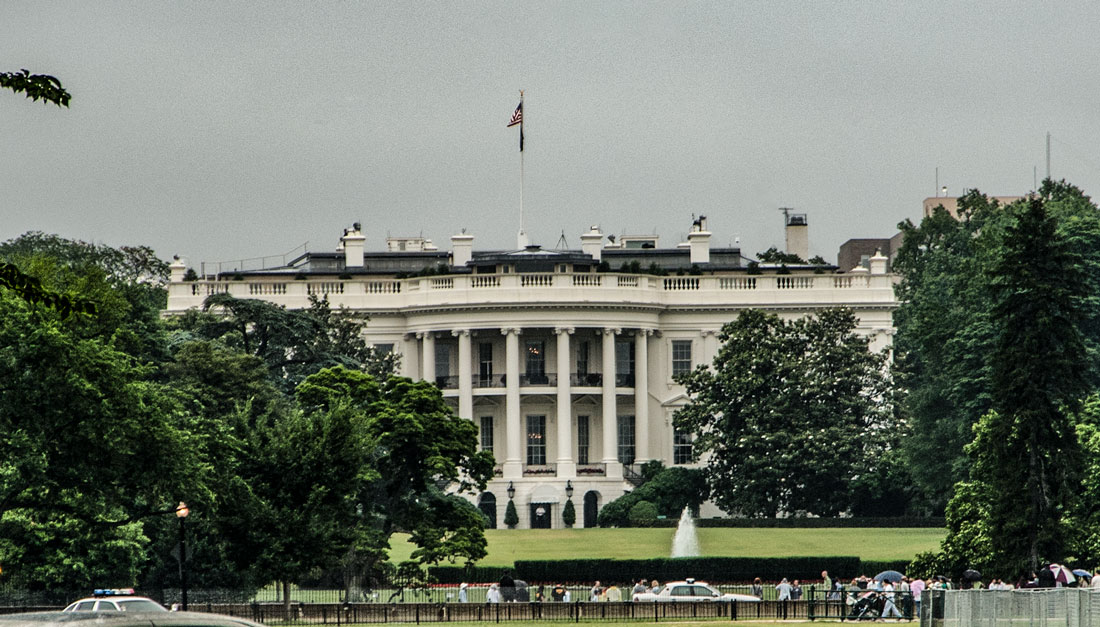

Before Washington D.C. was built in 1790, the area was sparsely settled countryside in Maryland and Virginia. French architect Pierre L’Enfant, who had fought in the American Revolution, designed the city to represent the nation’s founding democratic ideals. He organized it with radial axes connecting major architectural monuments such as the Capitol and the White house.

The precedent for this was the 16th century structure of Rome that created radial axes from the papacy to important churches. Rather than important religious buildings defining the architectural hierarchy, Washington D.C.’s city plan defined political buildings as of paramount importance. L’Enfant placed the Capitol building on the tallest point. The most important government buildings have a function beyond housing government departments. They are symbols of the state.

__1.jpg)

L'Enfante's 1791 plan.

The architecture of Washington and the design precedents that it represents are important in understanding how the early U.S. leaders envisioned the development and identity of their new country. The neoclassical nature of the city was a departure from pre-Revolutionary architecture in America, which was cubic wooden structures with some classical elements. Washington’s buildings were deliberately modeled on ancient Roman temples.

L’Enfant had been a French court artist who had lived at Versailles from age four. His Versailles connection supports the assumption that similarities between Versailles’ layout and Washington’s were an attempt to imitate Versailles, but he is not known to have compared the two. Instead, he said he wanted to create an original plan based on the city’s topography.

American architects looked to the example of Washington in public buildings and made the analogy between the new nation and Rome as the United States expanded westward to become its own vast empire. Neoclassical state houses and courthouses became the symbols of government all over the United States as new towns and cities sprang up.

The U.S. Capitol

The construction of the Capitol began in 1793. It was the result of a contest between designs, three of which were modeled after ancient classical buildings and the others which were mostly Renaissance styles. Thomas Jefferson, who was secretary of state, wanted the building to be a replica of an ancient Roman temple. He suggested that it be modeled after the Roman Pantheon, with a circular domed rotunda. Its design was intended to evoke the ideals that guided the nation’s founders as they framed the new republic.

British troops burned the Capitol in 1814 and it had to be rebuilt. Like most buildings in Washington D.C. built during the era, the building was mostly constructed by enslaved African Americans. The building has gone through several renovations, including the original wood and copper dome being replaced with the current cast-iron one in the mid-1800s.

It has been suggested that L’Enfant’s decision to place the Capitol on Jenkin’s Hill was intended to imitate the Roman Capitoline Hill, although it isn’t certain that that was the case. The decision to adopt the name ‘Capitol’ for the seat of the legislature is loaded with classical implications, but is not an accurate imitation of Rome. The Roman Senate did not actually meet on the Roman Capitoline Hill. The founding fathers got that false impression from a mistake in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Monk’s Tale that was repeated in Shakespeare plays.

The decision to name the building the Capitol broke from established naming tradition in America, so it is believed to have been a deliberate allusion to ancient Rome.

When an architect suggested a modern lantern design in the building, Jefferson responded, “You know my reverence for the Graecian & Roman style of architecture. I do not recollect ever to have seen in their buildings a single instance of a lanthern, cupola, or belfry.”

The building’s grandeur and symbolism have made it a worldwide icon of democracy. It has been widely copied, and is known worldwide through the media and a large number of films. The world reacted with horror when an unruly mob invaded and vandalized the building on Jan. 6, 2021, forcing members of Congress to evacuate.

The White House

The White House was originally a Georgian style estate. However, the British burned it in 1814 and it was rebuilt as a neoclassical mansion, again mostly by enslaved people. It is the architectural symbol of the U.S. executive branch and one of the most famous residences in the world.

"I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves," Michelle Obama, a descendent of slaves, famously said at the Democratic National Convention in 2016.

The Jefferson Memorial

The Jefferson Memorial’s architect, John Russell Pope, designed the memorial to reflect Jefferson’s admiration of Roman architecture. The memorial is modeled after the Pantheon in Rome and Andrea Palladio's Villa Capra. It also has similarities to Monticello, Jefferson’s Virginia plantation mansion.

Carvings in the pediment depict Thomas Jefferson with four other men who helped draft the Declaration of Independence. The memorial room is an open space circled by columns made of Vermont marble, with a 19-foot bronze statue of Thomas Jefferson standing beneath the dome.

The Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is a simple tapered stone obelisk with a pyramid top, inspired by ancient Egyptian architecture. The structure was completed in 1884 and is the tallest structure in Washington D.C.

The Lincoln Memorial

This neoclassic building, completed in the early 20th century, has a 19-foot seated statue of Abraham Lincoln. It is one of Washington’s most famous buildings, and was the site of Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I have a Dream” speech in 1963.

Among other famous Washington buildings that are neoclassical style are the U.S. Supreme Court Building and the Library of Congress.

Greek and Roman influence in images of American freedom is pervasive. Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom in battle, can be seen in American patriotic art as can Columbia, the goddess-like personification of the spirit of America. There are statues of George Washington dressed as a Roman emperor.

The bald eagle is the national animal and a prominent political symbol of freedom. The Romans used the eagle as a symbol of strength and of their supreme god, Zeus.

The Statue of Liberty, a gift from France in 1886, is Libertas, the Roman goddess of Liberty.

The United States has so many neoclassical courthouses that the style’s columns and statues representing justice and liberty have become synonymous with justice and the judicial system in the American mind. A popular image in statues is a blindfolded Lady Justice holding a set of balances in one hand and a sword in the other to represent that justice is not prejudiced. This personification of justice comes from the Greek Titaness Themis.

Trump’s executive order established a President’s Council on Improving Federal Civic Architecture intended to ensure that proposed federal buildings were "beautiful and reflective of the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American system of self-government."

The order cited ancient Greece and Rome and language from the constitution of the Italian city of Siena in 1309, saying that Washington and Jefferson modeled the most important buildings in Washington on the classical architecture of ancient Athens and Rome to remind citizens of their rights and responsibilities in maintaining and perpetuating the republic’s institutions. The driving force behind the order was the National Civic Art Society, which fought Frank Gehry’s Eisenhower Memorial for six years and forced the architect to make changes to his original design.

The order opened a long-standing debate over classical vs. modernist buildings in Washington. The American Institute of Architects has pushed back, saying the order is impractical and doesn’t account for the function of modern office buildings, which need to be efficient, affordable and equipped for technology and security. Trying to force new systems into old forms is difficult, inefficient and does not reflect who Americans are today, the institute has said.

The council created by the order will serve until Sept. 30, and then submit a report. The Biden administration has not indicated how it will respond.

See more photos of Washington D.C.

Check out these related items

Patriotic New York City

New York City, America's great atypical metropolis, taught me what America means. Here are my favorite patriotic sites in the city.

A Tale of Two Roman Cities

The amphitheaters, military garrisons, forums, trade and craft shops of two Roman colonial cities have emerged from the dust.

The Panthéon of Paris

The Panthéon in Paris, France's national mausoleum, embraces the contradictory themes of the nation's turbulent history.

The Racism of Confederate Statues

The racist past associated with the Confederacy and Confederate monuments has a complex history.

Whither the GOP?

The U.S. Capitol attack has opened up a debate on the future direction of the Republican Party and what it means for democracy.

Nations Within a Nation

The first Native American to become U.S. interior secretary must deal with a fraught history of government-Native American relations.