A Tale of Two Roman Cities

Photos by Forrest Anderson

In the first centuries BC and AD, the Romans spread their brutal Pax Romana throughout Europe, North Africa and the Middle East to become one of history’s largest empires. The empire’s expansion peaked under the emperor Trajan (r. 98-117), when between a sixth and a fourth of the world’s population lived under Roman rule. The empire stretched from northern England to the Euphrates and completely circled the Mediterranean Sea.

By the third century, this Roman tide retracted, leaving behind it a profound and lasting influence on language, religion, art, architecture, philosophy, law and forms of government in the colonial territories the Romans had governed. The Romans’ Latin language evolved into the Romance languages of the medieval and modern world. These influences eventually helped shape the great successor British, Spanish, French and Portuguese empires. However, most of the physical evidence of Roman colonial rule crumbled and was buried or scattered until modern times.

This was true in two of the most prominent Roman colonial settlements – Londonium, today the British capital London, and Lugdunum, now the southern French city of Lyon. London’s Roman walls fell or became incorporated into later structures as that city eventually developed into the capital of the British Empire. Lyon, which under Roman rule surpassed the importance of Paris, meanwhile evolved into France’s second largest city and a major center of trade and art.

In the past few decades, historical experts in both cities have pieced together the remnants of the two cities' Roman past, bringing back to life an understanding of how ancient Romans there lived.

Lyon

Lugdunum, a Gaulish name meaning the hill of the Celtic god of light, was the name of the Roman city sited on a hill west of the confluence of the Rhone and Saone rivers in what is today France. The city was an important Roman settlement for centuries, with trade routes stretching from it north, south, east and west through Roman territory.

This bronze plate, which was found broken into pieces, has the longest known inscription in the Gaulish language. It is written in Latin characters, evidence of the cultural fusion that resulted from the Roman conquest of Gaul. The calendar system, based on a very old counting system, was abandoned by Gauls under Roman rule. They adopted the Roman Julian calendar instead.

Julius Caesar conquered Gaul between 58 and 53 BC and two Roman governors of Gaul were ordered to found Lugdunum in 43 BC as a fortified settlement for a group of Roman refugees from a revolt in the nearby town of Vienne. One of the governors, Munatius Plancus, became the principal founder of Lugdunum.

A carving of Roman soldiers found in Lyon, now at the Lyon Gallo-Roman Museum.

Within half a century, Lugdunum was the administrative center of Roman Gaul and Germany. The town was strategically important for four centuries as a staging ground for Roman expansion into Germany and as the governing, commercial and financial center of Gaul.

Emperors and members of the imperial family visited Lugdunum. Agrippa, Tiberius and Germanicus were among governor generals who served there. A number of emperors contributed to the city’s expansion. The emperor Claudius, who was born in Lugdunum, stopped there on his return from his conquest of Britain in 43 AD and again in 47 AD. He declared nobles of the town eligible to serve in the Roman Senate. When Rome burned in 64 under the emperor Nero, citizens of Lugdunum contributed money to its rebuilding, and Nero reciprocated in the same amount when Lugdunum suffered a similar fire a few years later, according to textual evidence.

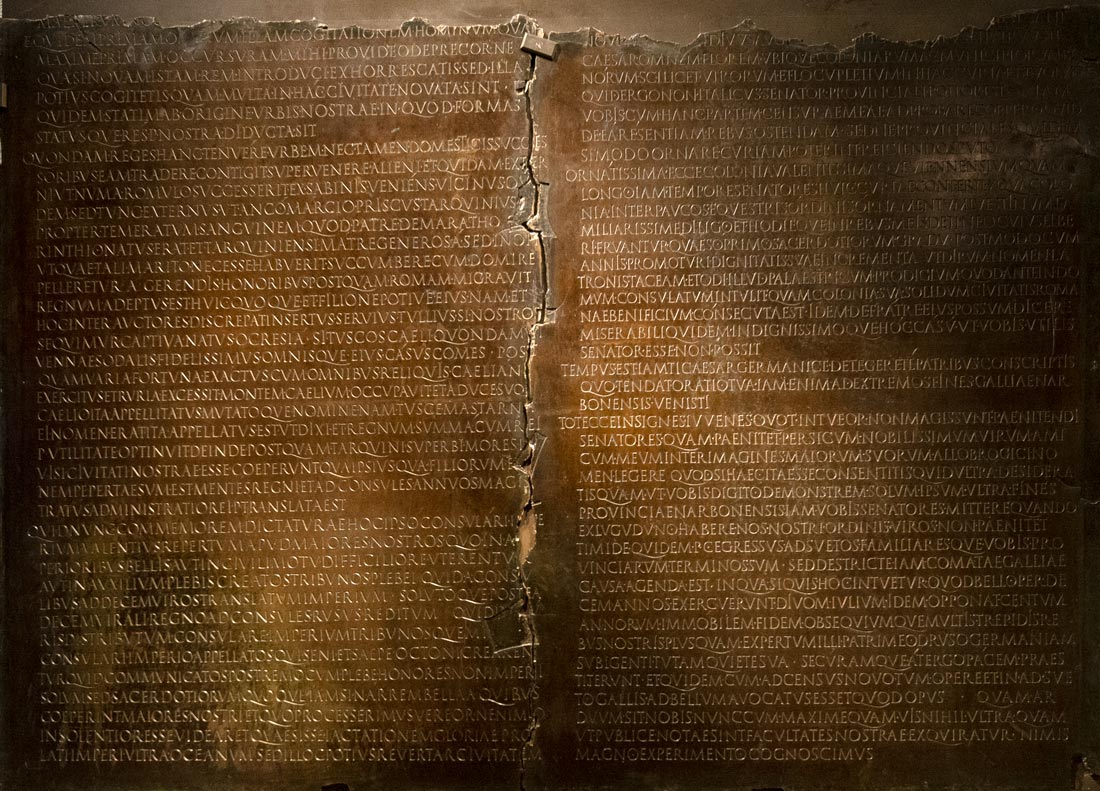

This large bronze tablet from the mid-1st century is the text of a speech by the Emperor Claudius (r. 41-54), who was born in Lyon in 10 BC. The speech was given to the Roman Senate because some of the Gaulish nobility had petitioned to be given the same rights as Roman citizens to be elected magistrates in Rome and be part of the Senate. The senators, many of whom remembered the resistance that Gauls had put up to Roman rule, opposed the petition but Claudius intervened in their behalf in this speech. The tablet is one of the most valuable artifacts at the Lyon Gallo-Roman Museum.

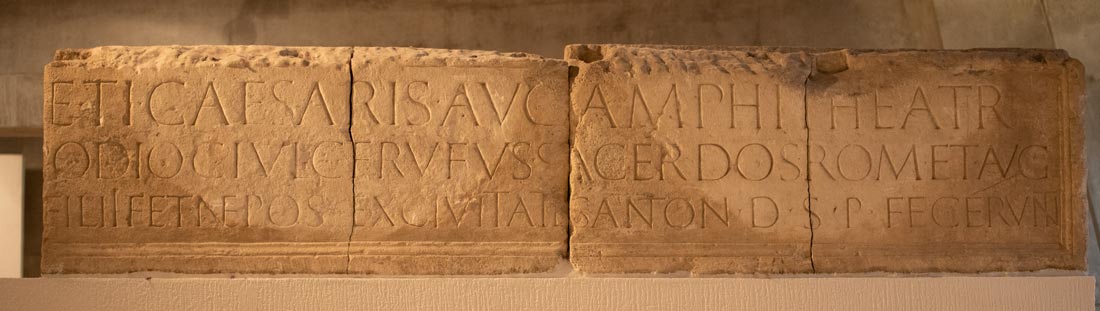

This Roman dedicatory inscription, now in the Lyon Gallo-Roman Museum, was discovered in 1958 near Lugdunum's ancient Roman amphitheater. The inscription, which refers to the Emperor Tiberius, reveals that a wealthy citizen named Caius Julius Rufus paid for the amphitheater. Local citizens were expected to both serve in public offices and pay for the urban infrastucture.

The city had an imperial cult sanctuary engraved with the names of 60 Gallic tribes. The image of the altar was engraved on coins made at Lugdunum’s imperial mint. The city had an amphitheater and a forum, fountains, public baths and wealthy homes which were supplied with water from four Roman aqueducts.

A huge Roman mosaic from the Lyon area in the Lyon Gallo-Roman Museum. This world-class museum has a number of Roman mosaic floors that are in near perfect condition. This photo also shows a gallery in the Lyon Roman-Gallo museum, an innovative underground museum built into the side of the cliff next to the Roman amphitheater so that it doesn't visually interfere with the ancient ambience of the amphitheater.

It is not known for sure whether Lugdunum had a Roman circus, but this mosiac and a number of other Lyon artifacts are decorated with scenes from a Roman circus.

Lugdunum was the principal manufacturing center for pottery, metalworking and weaving in Gaul and the city crafted many items for export. The city had an elite of government officials, a wealthy merchant and craftsman class, and below them workers and slaves. Among the most honored were boatmen who dominated the wine and oil trades from Italy, Spain and Gaul. The city had a large cosmopolitan population of Italians, Greeks, and immigrants from Asia Minor, Syria and Palestine. There were a variety of temples to various gods.

An ancient Roman boat excavated in the port at Lyon. Lyon Gallo-Roman Museum.

Roman slave shackles from the Lyon area.

Among local devotees were Christians. The first known Christian community in Gaul was established in Lyon in the 2nd century, led by a bishop named Pothinus who probably was Greek. In 177, this community became the first in Gaul to suffer persecution and martyrdom. A letter from Christians in Lugdunum to other Christians in Asia, which was preserved by Eusebius, said that mob violence against Christians ended with them being publicly interrogated in the forum by officials. The Christians confessed their faith and were imprisoned until a Roman official authorized their persecution. About 40 of them were martyred, either by dying in prison, being beheaded or being killed by beasts in the public arena. Pothinus was among those killed. The Christians’ ashes were thrown into the Rhone river. The Christian community in Lugdunum eventually recovered and continued to grow in size and influence, led by prominent church father Bishop Irenaeus.

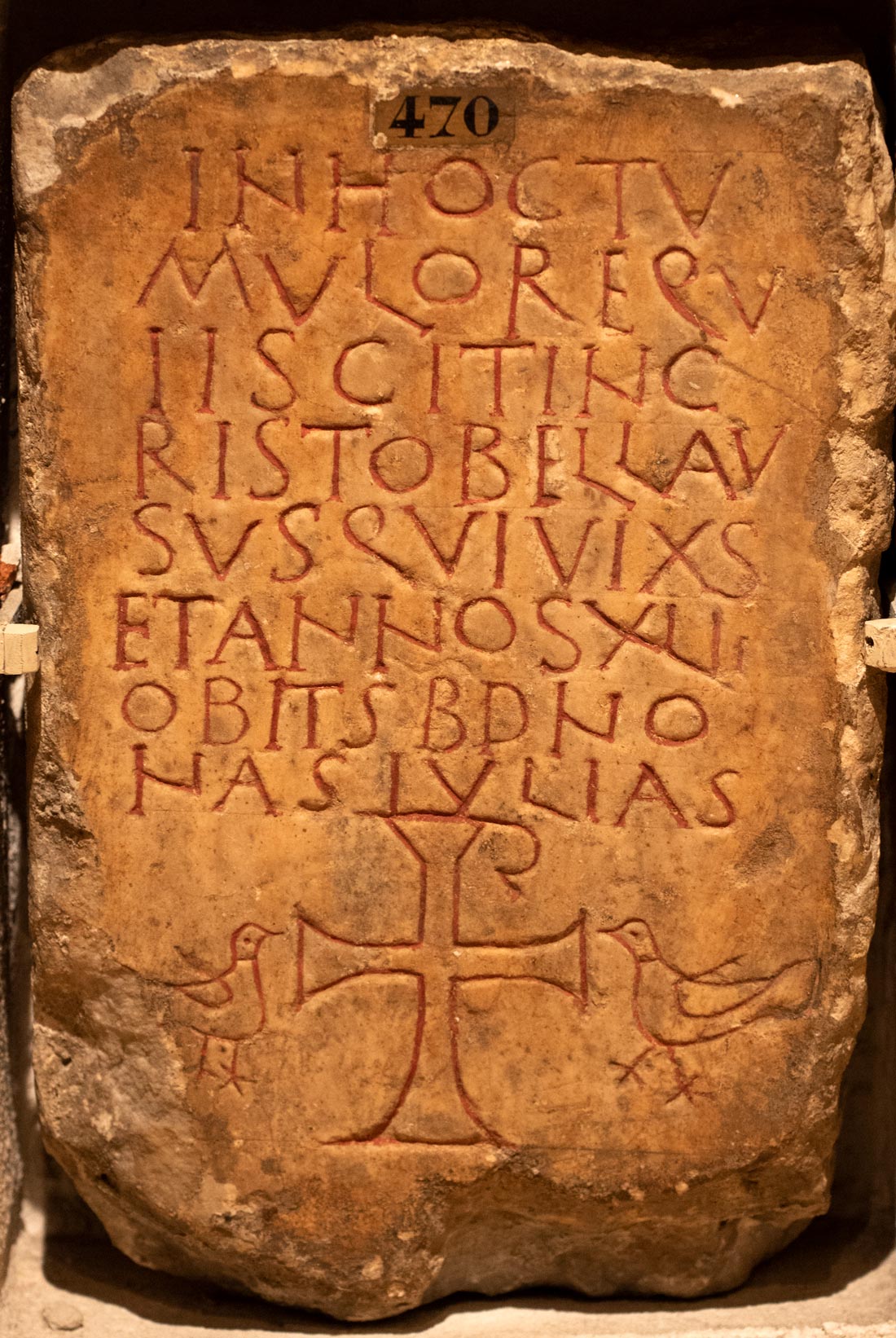

A Christian tombstone. Despite the early presence of and martyrdom of early Christians in Lugdunum, there is no physical evidence of them until the 3rd century, when such tombstones were inscribed. Much of what is known about Lyon's Roman past is from inscriptions on stone monuments and tombstones. The Lyon Gallo-Roman Museum has a collection of early Christian tombstones from the Lyon area.

Lugdunum citizens were prominent enough to participate actively in power struggles in Rome. In the 2nd century, just such a conflict resulted in a bloody battle being fought in Lugdunum, where one of the rivals, Clodius Albinus, was defeated. One account which may be exaggerated says that the battle involved 300,000 men and was one of the largest ever involving Roman armies. Albinus committed suicide in a house near the Rhone and his head was sent to Rome as a warning to his supporters. The city was severely damaged in the battle, and historical and archeological evidence indicates that it never fully recovered. Its importance declined and it became the capital of a much smaller region. Power and trade importance shifted to other locations until the Western Roman Empire disintegrated in the 5th century.

Roman Emperor Caracalla (212-217). Lyon Gallo-Roman Museum.

With the end of the empire, the vestiges of Roman Lugdunum slowly sank into the ground or were carted off. Many of the stone blocks from Roman buildings were used in later construction, their Latin inscriptions deliberately showcased on the walls of houses, fountains, churches and bridges in Lyon. During the Renaissance, when an interest in things Roman revived, collectors began to make inventories of these Roman elements. Salvaged from demolitions of buildings, many inscriptions ended up in individual collections. In 1801, a museum of such Roman artifacts was housed in a former Benedictine monastery. The collection grew throughout the 19th century as Roman artifacts were found at construction sites. Old Roman mosaic floors with depictions of Roman gods and scenes were found and removed to the museum in complete panels.

Researchers of the 18th-19th centuries began to supplement the museum’s collection with archeological digs, combing construction sites for evidence of ancient ruins. During the extension of a railway line, a vast section of a Roman cemetary was found, including not just stone inscriptions but coins, earthenware crockery, lamps, glass, jewelry, iron and bone objects.

In the 20th century, archeological excavations were held on the hillside, now called Fourviere, where Roman Lugdunum was located. A quest to find the Roman amphitheater was a major motivation, as it was venerated as a site of Christian martyrdom. The vestiges of a small theater on the hillside had been known for a long time and it was believed that remains of the amphitheater were nearby. From 1935-1980, a Roman temple, streets and shops were found along with many architectural elements, fragments of statues and inscriptions. The amphitheater was finally uncovered by the end of the 1950s.

The multicolored floor of the smaller of two theaters in the amphitheater complex. The floor was made up of stones from all over the Mediterranean region. Below, a model of the amphitheater, which consisted of an arena (left) and a smaller covered theater called an odeon (right), in which oratories and plays were presented.

This statue was among artifacts uncovered near the amphitheater.

In 1975, the building of an underground railway line uncovered one of the richest districts of the Roman city. This resulted in an increase in research and archeological activity. The remains of a temple and several clusters of housing were uncovered, and in the early 2000s, near one of Lugdunum’s ancient ports, six large Roman boats were excavated.

Despite the extensive excavations, there is mostly a blank from the period of the Christian martydum in 177 to the appearance of the first Christian buildings. A large baptistry was built on the banks of the Soene, near the cathedral of Saint Jean, that dates from the second half of the 4th century. There also were funerary basilicas relating to the cult of Christian martyrdom built as early as the beginning of the 5th century, and large cemeteries developed around them. The earliest Christian grave inscriptions in the Lyon Gallo-Roman Museum are from the 3rd century.

Artifacts from Lyon’s Roman era and before it are today housed in the remarkable Lyon Gallo-Roman. The museum was built into the cliff next to the amphitheater, making it almost invisible, to preserve the ancient ambiance of the amphitheater. The only part the museum that is visible on the cliff are an unobtrusive building at the top and two pods with glass windows in the cliff which allow visitors to the museum to view the amphitheater from partway up the cliff. Visitors start at the top of the museum and work their way down through the museum galleries along a spiraling ramp until they emerge at the amphitheater at the bottom of the cliff.

Londinium

The Roman settlement of Londinium was established on the site of what is now London, England, in about AD 43. Like Lugdunum, it was located by a river – in this case the Thames. It became a major port and commercial center in Roman Britain until it was abandoned by the Romans in the 5th century.

The Romans created London – it was rolling open countryside before the Roman legions arrived. However, the general area apparently was important strategically and for trade purposes before the Romans.

Above, the tombstone of a Roman soldier and, below, Roman weapons. Both were found in London. This and other artifacts shown below are in a superb exhibition on Roman life in Londinium that is at the Museum of London.

The city was originally a fortified Roman garrison. In the year 60 or 61, after a local Roman-allied Celtic king died, the Romans confiscated his property and that of his nobles. When his widow Boudica objected, the Romans flogged her, raped her two daughters, and enslaved their nobles and relatives. Boudica revolted against the Romans, overwhelming 200 Roman soldiers who were sent to defend a nearby Roman colony, probably from the garrison at Londinium. The 9th Roman Legion was ambushed and annihilated. G. Suetonius Paulinus had been leading Rome's 14th and 20th Legions in an invasion of Anglesey that is now known as the Menai massacre. He heard of the rebellion and returned to Londinium. He decided to pull out of the city, leaving it undefended. Many inhabitants accompanied him, but those who stayed behind were slaughtered by the rebels. Archeaological excavation in the city has revealed a layer of red ash indicating destruction by fire at this date.

This skull is believed to date from Boudica's revolt.

Suetonius then returned to defeat Boudica’s army, slaughtering as up to 70,000 men and camp followers. A tradition is that the battle occurred at King’s Cross in London, but no evidence has been found of that.

The city was then rebuilt as a Roman one. Like Lugdunum, Londinium expanded rapidly. It became Britain’s largest city. As with Lugdunum, the name Londinium probably was based on a native place name that was Latinized. Also like Lugdunum, Londinium was a nexus of river and road traffic.

Londinium was an important port for trade between Britain and the Roman provinces in Europe. Scraps of armour, leather straps, and military stamps on building timbers suggest that the site was constructed by the city's legionaries. Major imports included fine pottery, jewelry, and wine. Only two large warehouses are known, implying that Londinium was a bustling trade center rather than a supply depot and distribution center.

It had only a modest forum at first, which has been excavated. It had an open courtyard with a basilica and several shops around it. The basilica would have been where law cases were held and the local senate met. It also had a shrine in it. A second great forum was built around the year 120.

Londinium's amphitheatre, built in AD 70 as a simple wooden structure and then improved upon and expanded in stone, is situated at Guildhall. The Romans used it for public events, animal fighting, public executions and gladiatorial combat. When the ancient Romans left in the 4th century, the amphitheater lay neglected for hundreds of years. By the 12th century, the Guildhall was built next to it. Parts of the amphitheater are on display at the Guildhall Art Gallery.

Remains of the Roman Amphitheater at the Guildhall Art Gallery.

Archaeologists spent a century of searching for the amphitheater before it was found in 1988 beneath Guildhall Yard. After the Romans left Britain in the 4th century, many of the amphitheater's stones were carted off for use in other structures. It lay in ruins until the 12th century, when the area was reoccupied and the Guildhall was built. The remains of the amphitheater are in the Guildhall Art Gallery basement. They include the original walls, drainage system and sand which was used to soak up blood from wounded gladiators. Digital projection fills in the gaps in the ruins so visitors can visualize what the amphitheater was like.

There is no surviving source that indicates Londinium was the Roman capital of Britain, but archaeological evidence indicates that it was. A large building was discovered that has a foundation dating to this era. It is assumed to have been the governor's palace. It had a garden, pools and several large halls, some of which had mosaic floors. Another site dating to this era was a bathhouse.

Reconstructions of Roman rooms using actual Roman artifacts and reconstructions of Roman furniture at the Museum of London.

Londinium grew up around a point on the River Thames narrow enough for the construction of a Roman bridge but deep enough to handle seagoing ships. The remains of a massive pier base for such a bridge were found in 1981 near London Bridge. A large Roman port complex on both banks near the bridge was found. Archaeologists have uncovered numerous goods imported from across the Roman Empire in the mid-1st century, indicating that Londinium was a merchants’ community.

Of fifteen British routes recorded in the 2nd- or 3rd-century Antonine Itinerary, seven ran to or from Londinium. Most were built near the time of the city's founding.

As in Lugdunum, cemeteries were located outside the city. A round temple has been found west of the city and inscriptions suggest a temple of Isis was located near the southern Thames bridge in Southwark.

Londinium was at its peak in the early 2nd century, with many stone houses and public buildings. Some areas had townhouses. The town had piped water and a drainage system. The three-storey basilica was the largest in the Roman empire north of the Alps. Londinium’s marketplace rivaled the markets in Rome and was the largest in the north before Trier, Germany, became an imperial capital. Londinium’s temple of Jupiter was renovated, public and private bathhouses were built, and a fort was erected for the city garrison.

Roman pottery, which was traded widely throughout the Roman world, with a map of the empire.

Emperor Hadrian visited Londinium in 122. Impressive public buildings from around this period may have been constructed in preparation for his visit or during the rebuilding that followed the "Hadrianic Fire". This fire, which archaeologists have discovered destroyed much of the city, is not recorded by any surviving source.

A temple complex with two Romano-British temples was excavated in Southwark in 2002-2003. A marble slab with a dedication to the god Mars was discovered there. The inscription mentions the Londoners, the earliest known reference to the people of London.

By the second half of the 2nd century, Londinium began to shrink in size and population, possibly because of a plague that was decimating other areas of Western Europe or because Roman expansion in Britain ended after Hadrian decided to build his wall. Archaeologists have found that much of the city after this date was covered in dark earth that accumulated relatively undisturbed for centuries.

Roman gold coins from London, divided by the reigns of emperors. The Romans had an imperial mint in Londinium.

Sometime between 190 and 225, the Romans built a defensive wall around the land side of the city. The wall and its gates survived until they were demolished in the 17th-18th centuries to allow widening of road. The wall’s line still roughly defines the City of London’s perimeter.

A surviving section of the Roman wall near the Tower of London, with a statue of the Roman emperor Trajan.

Septimius Severus defeated Albinus in 197 and shortly afterwards divided the province of Britain into upper and lower halves. The economic stimulus provided by the wall and by Septimius Severus's campaigns in Caledonia somewhat revived London's fortunes in the early 3rd century. The London Mithraeum rediscovered in 1954 dates from around 240. From about 255 onwards, raiding by Saxon pirates led to the construction of a riverside wall running roughly along today’s Thames Street, which was the shoreline. Collapsed sections of this wall were excavated in the 1970s.

In 286, the emperor Maximian issued a death sentence against Carausius, admiral of the Roman navy's Britannic fleet, on charges of having abetted Frankish and Saxon piracy and embezzled recovered treasure. Carausius revolted, but his Gallic base was sacked and his treasurer assassinated him. In 296, Chlorus mounted an invasion of Britain that prompted the treasurer Allectus's Frankish mercenaries to sack Londinium. They were stopped by the arrival of a flotilla of Roman warships on the Thames, which slaughtered the survivors. New forum baths were constructed around 300 as a memorial to the return of Londinium to Roman control. They were elaborate, with a frigidarium with two southern pools and an eastern swimming pool.

After the revolt, the British administration was restructured with new provinces in Britain. Londinium is believed to have been the capital of one of them. The governor’s palace and large forum seem to have fallen out of use around 300, but in general the first half of the 4th century appears to have been prosperous for Britain, as villa estates around London flourished. The London Mithraeum was rededicated, probably to the god Bacchus.

A 12th century document claimed that the city’s Christian community was founded in the 2nd century, but there is no corroborating evidence. The location of Londinium's original cathedral is uncertain, although the present structure of St. Peter on Cornhill, built after 1666, is tied in medieval legends to the city’s earliest Christian community. In 1995, a large ornate 4th-century building on Tower Hill similar to St Ambrose's cathedral in Rome was discovered. It was made of stone taken from other buildings and probably was dedicated to St. Paul.

From 340 on, Picts and Gaels repeatedly attacked northern Britain. Twenty-two semi-circular towers were added to the city walls and the river wall was repaired. In 382, Magnus Maximus organized British-based troops and tried to establish himself as emperor over the west. He was defeated by Theodosius I at the Battle of the Savein in 388.

With few troops left in Britain, Londinium and other British-Roman towns declined drastically. Excavations of the port show signs of rapid disuse. Between 407 and 409, barbarians overran Gaul and Hispania, weakening communication between Rome and Britain. Trade broke down. Officials were unpaid and Roman-British troops elected their own leaders. Constantine III declared himself emperor over the west and crossed the Channel, an act which is considered the Roman withdrawal from Britain since the emperor Honorius subsequently directed the Britons to look to their own defense rather than sending another garrison force to Britain. Archaeological evidence of Londinium during this period is minimal.

Roman Britain enjoyed a period of luxury and plenty perhaps because of reduced Roman taxation. Archaeologists have found evidence that a few wealthy families continued to maintain a Roman lifestyle until the mid-5th century, living in villas and importing luxuries. Invasions that established Anglo-Saxon England began in the 440s and 450s. By the end of the 5th century, Londinium was largely a deserted ruin, its large church on Tower Hill burned to the ground.

Tribal kingdoms were established, and the Roman city area was administered as part of the Kingdom of the East Saxons – Essex. With the Viking invasions of England, King Alfred the Great moved back within the Roman walls. The river wall collapsed by the 11th century.

Research on human remains in Roman cemeteries of Londonium indicate that the city was ethnically diverse, with inhabitants from across the Roman Empire.

Skeleton of a young Roman woman who was buried in London.

Many of the inhabitants had African ancestry. A 2016 study of 20 bodies from various periods suggested that at least 12 had grown up locally, four were immigrants, and four were unclear.

There are many Roman ruins under London. Understanding them can be difficult because it is hard to differentiate Roman gravel roads from natural rock, remains from wooden structures are minimal and easily missed and stone from stone buildings was reused after the Roman period. The first extensive archaeological review of the Roman city was done in the 17th century after the Great Fire of 1666. It revealed that there was no evidence for the belief that St. Paul’s had been built over a Roman temple to the goddess Diana. Extensive rebuilding of London in the 19th century and after German World War II bombing uncovered more Roman ruins. The construction of the London Coal Exchange led to the discovery of a Roman house in 1848.

In 1947, the city's northwest fortress of the Roman city garrison was discovered. In 1954, excavations of what was thought to have been an early church revealed the London Mithraeum. Archaeologists began the first intensive excavation of the waterfront sites of Roman London in the 1970s. Another phase of archaeological work followed deregulation of the London Stock Exchange in 1986, which led to new construction in the financial district.

Major finds from Roman London, including mosaics, wall fragments, and old buildings, are housed in the Museum of London and Museum of London Docklands, a separate branch dealing with the history of London's ports. Other artifacts from Roman London are held by the British Museum.

Roman-era stretches of the city wall are visible near Tower Hill Station, in a hotel courtyard at 8–10 Coopers Row, and in St. Alphege Gardens off Wood Street. A section of the river wall is in the Tower of London. The southwestern tower of the Roman fort northwest of the city can be seen at Noble Street. Roman sites occasionally are incorporated into the foundations of new buildings for future study, but are not generally public.

More photos of the Roman Amphitheater, Lyon, France

Check out these related items

Britain and Greece’s Parthenon Dispute

What are the chances that two men from one family set off international disputes by carting off treasures from Greece and China?

Traces of an Ancient Superpower

Traces of an ancient Chinese superpower remain far away in Japan, the eastern end of the Silk Road.

Paris’s Oldest Church Restored

Paris' oldest church, Saint Germain des Prés, is emerging from layers of grime and soot as a meticulous restoration reveals its vibrant color.

Scaffolding the World

Finding a historical site shrouded in scaffolding is disappointing, but it is a valuable tool for preserving the world's heritage.

What is the Louvre?

The former palace, the world's largest museum, music video and fashion show venue, and global brand has never been more cool.

The World Mourns Notre Dame

Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, France's national cathedral, was badly damaged in a fire.