Nations Within a Nation

Photos by Forrest Anderson; painting in the public domain.

When Deb Haaland became the first Native American Interior Department secretary this week, she took over an agency with a fraught history of handling relations between the United States and the Native American nations within U.S. borders.

The history of Native Americans is extremely complex and is intertwined with and often overshadowed by other American narratives such as the westward expansion, the Civil War and general racial discrimination. Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet member, will be responsible for managing the nation’s public lands as well as its many treaties with native tribes. The Interior Department oversees a fifth of U.S. land and 1.7 billion acres of coasts, managing national parks and other public lands and protecting biological and culturally important sites as well as natural resources. The sites include many that are part of Native American history.

The United States is far from the only nation that has struggled with handling relations with indigenous peoples – China, Russia and Australia are among many prominent examples. Haaland’s appointment reflects another chapter in the continuing interaction between Native Americans and the U.S. government.

The history of Native Americans in a nutshell is one of removal from lands they lived on for thousands of years before Europeans arrived, but the nuances of the narrative make it difficult to point to single culprits or resolve historical issues. It is a lesson for all of us as our nation continues to work out complex racial, cultural and environmental dilemmas.

The line drawn between Indian Territory and the state of Arkansas in 1834, Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Focusing in on the largest Native American tribe – the Cherokee – helps to illuminate the basic story.

For thousands of years, the Cherokee and their ancestors occupied vast lands and towns in river valleys and along mountain ridges of South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama. Their language was Iroquoian, which indicates that they either split off from northern Iroquoian-speaking tribes that migrated south or the opposite happened. A Cherokee oral tradition supports a migration south from the Great Lakes region.

The Cherokees became farmers who cultivated a form of corn that allowed their population to grow and chiefdoms composed of several villages to form. They celebrated corn in their ceremonies.

They developed a matrilineal society in which woman were considered the life givers because they gave birth to children and did the farming. When a man married, he joined his wife’s clan. Women ran the villages as men were away hunting. For thousands of years, the Cherokee hunted and farmed in ways that sustained the land and supply of deer and other game. They occasionally had armed conflicts with other tribes trying to encroach on their lands, and took captives as slaves who they assimilated into their societies.

Spanish explorers came across the Cherokees as early as the 1500s and early European traders had a small-scale trading system with them in the late 1600s, sometimes marrying Cherokees.

As British and French colonists in the Americas came into conflict in the early 18th century, the Cherokees allied with the British and fought tribes who were allied with the French. The British considered the Cherokees valuable trading partners because they supplied mountain deerskins considered higher quality than those supplied by coastal tribes. The Cherokee signed treaties with the British and prominent Cherokees went to London on diplomatic missions.

The Cherokees caught smallpox from the British that killed nearly half of the Cherokee population within a year in 1738-39. Hundreds more committed suicide in despair.

The British government forbade British settlement west of the Appalachians to protect the Cherokees from colonial encroachment. However, as more British migrated to the Americas and Virginians pushed into the Southeast to grow cotton, the British found this ban increasingly difficult to enforce. With the British defeat in the Revolutionary War, the prohibition evaporated.

White squatters settled on Cherokee lands in Tennessee in the 1770s and sparked Cherokee attacks when they tried to do so in Kentucky, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia and North Carolina. In the 1780s, provincial militias retaliated against the Cherokees and destroyed more than 50 Cherokee towns. The massacres broke the main Cherokee resistance and forced surviving town leaders into treaties with the new states of the Union, but some Cherokees continued a two-decade guerrilla war against settlers that ended with the Cherokees ceding lands to the states.

Cherokee land was much reduced at the same time that the Cherokee had overhunted deer to sell their hides in the international deer trade. As their economic base of hunting and agriculture declined, the Cherokee were forced to adapt to European ways.

European American settlers became government agents and traders dealing with the tribes. Some married Cherokee women and their children became prominent leaders of Native American tribes, accelerating the Cherokee move toward Europeanization. The Cherokees began to build a new society modeled on Southern White customs and social structures. The first U.S. President, George Washington and subsequent presidents encouraged this, seeking to “civilize” southeastern Native Americans by persuading them to abandon their communal land system and settle on individual farmsteads. Pigs and cattle were introduced and became the principal sources of meat as the deer population declined. The government gave the tribes spinning wheels and cotton seed and taught them to fence and plow the land. Women were taught to weave, and men were taught to run gristmills, cotton plantations and smithys. Women began to lose power in Cherokee society.

The Cherokees formed a national government with a three-branch constitution modeled on the U.S. Constitution, a capitol in New Echota, Georgia, a police force, a printing press and a newspaper. Missionaries taught the Cherokees Christianity, and Cherokee children were educated at missionary boarding schools. Sequoyah created the first written Cherokee language in the early 1800s and taught Cherokee children to read. By the 1820s, they had a higher rate of literacy than Whites in Georgia did.

New roads and ferries opened up Cherokee land, bringing more settlers. Enslaved Africans were brought in to labor on Cherokee plantations, some of which became large and prosperous. There were continuing conflicts with Whites over runaway slaves joining the Cherokees because the Cherokee system allowed enslaved people to assimilate into Cherokee society.

The Cherokee allied with the United States against the pro-British Creek in the War of 1812, with Cherokee warriors playing a major role in General Andrew Jackson’s victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. The Cherokee commander Major Ridge built a large plantation in Rome, Georgia, and sent his sons and nephews to New England to be educated in mission schools. His protégé John Ross, a descendent of several generations of Cherokee women and European American fur traders, also built a plantation in Tennessee. These Cherokees lived a European elite lifestyle that differed greatly from the traditional village way of life that most Cherokee continued to follow.

As White settlers encroached on Cherokee land, many Cherokees voluntarily moved to Arkansas, Missouri and Texas in the late 1700s. The federal government began working on persuading other Cherokees to move west in 1802 and in 1815 established a Cherokee Reservation in Arkansas. Cherokee conflict with the Osage Nation led to establishment of Fort Smith, Arkansas, between the Cherokee and Osage communities. In 1825, the Osage were forced to cede land in Missouri and Arkansas to make room for the Cherokees and Creeks. The Creek were forced to cede their last lands in 1825. They were walked West double file, some in chains, without food supplies or other help. Some 3,500 died, prompting a Choctaw leader to name the trek a “trail of tears and death.”

“Thus in two or three days about 8,000 people, many of whom were in good circumstances, and some rich, were rendered homeless, houseless and penniless, . . . while the soldiers, it is said, would often use the same language as if driving hogs, and goad them forward with their bayonets,” the Reverend Daniel S. Butrick reported.

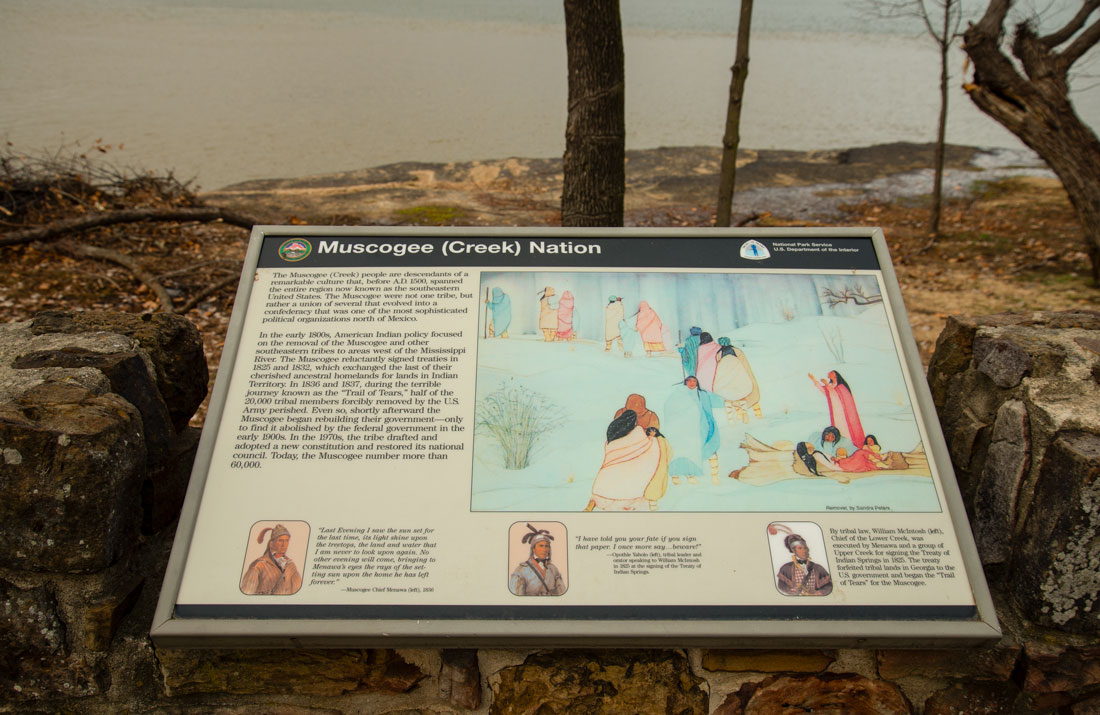

The Muscogee (Creek) were the first tribe to lose all of their land east of the Mississippi and to embark on what became known as the Trail of Tears. Other tribes followed.

After gold was discovered on Cherokee land in Georgia in 1829, launching the first U.S. gold rush, state officials demanded that the federal government expel the Cherokee. President Andrew Jackson agreed, insisting that removal to the West was necessary to prevent extinction of the Cherokees. Some among the Europeanized Cherokee elite who had the means to move West concurred. Modern analyses have concluded that the Southeast economy could have accommodated both the Cherokee and new settlers, so the removal was entirely unnecessary.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act that authorized the removal of Native Americans east of the Mississippi. The act gave the U.S. government power to exchange native land east of the Mississippi for land to the west of the river that the United States had acquired as part of the Louisiana Purchase. This land, called Indian Territory, was in what is today Oklahoma.

The Cherokee Nation won a U.S. Supreme Court case protecting their rights as a sovereign nation, but Jackson ignored the ruling. Georgia sold Cherokee lands to its citizens in a land lottery and the state militia occupied the Cherokee capital of New Echota while the Cherokee National Council fled.

A small group led by Cherokee elites Major Ridge, his son John Ridge and Elias Boudinot believed that relocation was inevitable and the Cherokee needed to make the best deal they could to preserve their rights in Indian Territory. In 1835, the men signed the Treaty of New Echota stipulating terms and conditions for the removal of the Cherokee nation. In return, they were offered a large tract in the Indian Territory, $5 million, and $300,000 for improvements on the new land.

John Ross, incensed by this sellout of the Cherokees, gathered more than 15,000 signatures in a petition to the U.S. Senate claiming that the treaty was invalid because the majority of Cherokees opposed it, but the Senate passed the treaty anyway in 1836. Two years later, President Martin Van Buren ordered the Cherokees evicted from their land and sent General Winfield Scott and 7000 troops to enforce the order. More than 16,000 Cherokee were forcibly relocated west to Indian Territory in 1838-1839.

Tales of the eviction are horrific – people forced from their homes at bayonet point and not allowed to take any provisions or even a second change of clothing. Many Cherokee were locked in stockades for weeks and then marched more than 800 miles across Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri and Arkansas. Others migrated by boat on waterways. Epidemics broke out along the way and between 2,000 and 4,000 Cherokees died from disease, exposure and starvation. Among the migrating Cherokees were enslaved African Americans and European Americans who had married into Cherokee families.

The Cherokee resisted ceding their land and heading west until they were forced by U.S. troops along the Trail of Tears.

After many Cherokees died, Ross persuaded Scott to allow the remaining ones to conduct their own removal rather than have troops force them West.

Cherokee law prescribed the death penalty for Cherokees who sold lands without authorization, and a party of 25 Ross supporters killed the two Ridges and Boudinot.

In all, the Cherokee participated in more than forty treaties with Europeans and the United States, resulting in a 90 percent reduction in Cherokee land boundaries. In 1721, the Cherokees owned all of Kentucky, ¾ of Tennessee, about half of Georgia and South Carolina and about a fourth of North Carolina. By 1830, they owned only a small corner of Tennessee, a tiny piece of North Carolina and Alabama and a corner of Georgia.

Cherokee living along the Oconaluftee River in the Great Smoky Mountains withdrew from the Cherokee Nation and got North Carolina citizenship which exempted them from forced removal. More than 400 Cherokee hid in the remote Snowbird Mountains or stayed on reserves in Southeast Tennessee, North Georgia and Northeast Alabama as citizens of their states. Mostly mixed-race and Cherokee women married to white men, they were the ancestors of the now federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and some state-recognized tribes.

The Cherokees who survived the Trail of Tears migration were supposedly a sovereign nation with their own government and laws, but were subject to some supervision by U.S. troops operating in forts such as Fort Smith, Arkansas, which was on the border between Indian Territory and Arkansas. The fort originally had been established in 1817 to keep the peace between Cherokee and Osage tribes, and later served as the agency for the removal of Native Americans from several tribes to Indian territory. Troops became involved in controlling a thriving market in selling cheap whiskey to Native Americans in Indian Territory, a conflict called the Arkansas Whiskey War.

Fort Smith Arkansas, today a historical site.

Fearful White residents of the new State of Arkansas requested that a permanent military garrison be placed on their border with Indian Territory as more Native Americans moved to the territory. Fort Smith was expanded to serve that function.

It also was a supply depot for military units marching to the Mexican-American War and for frontier troops posted in Indian Territory. It was taken over by the Confederates as a supply base during the Civil War.

A U.S. District Court was established at Fort Smith in 1872. The court’s jurisdiction included Indian Territory.

The courthouse at Fort Smith.

Tribal courts in Indian territory had no jurisdiction over non-Indian settlers in the territory, so they could murder and steal without fear of tribal jurisdiction. A system of federal marshals and deputies arose to apprehend offenders and take them to Fort Smith for trial. It was among the most dangerous law enforcement work in U.S. history, with many deputies and marshals being killed. In one case I researched for a descendant of a U.S. marshall who was killed, his orphan daughter was taken in and raised by a wealthy Native American woman who was married to a White man. The story illustrates the intercultural nature of the society.

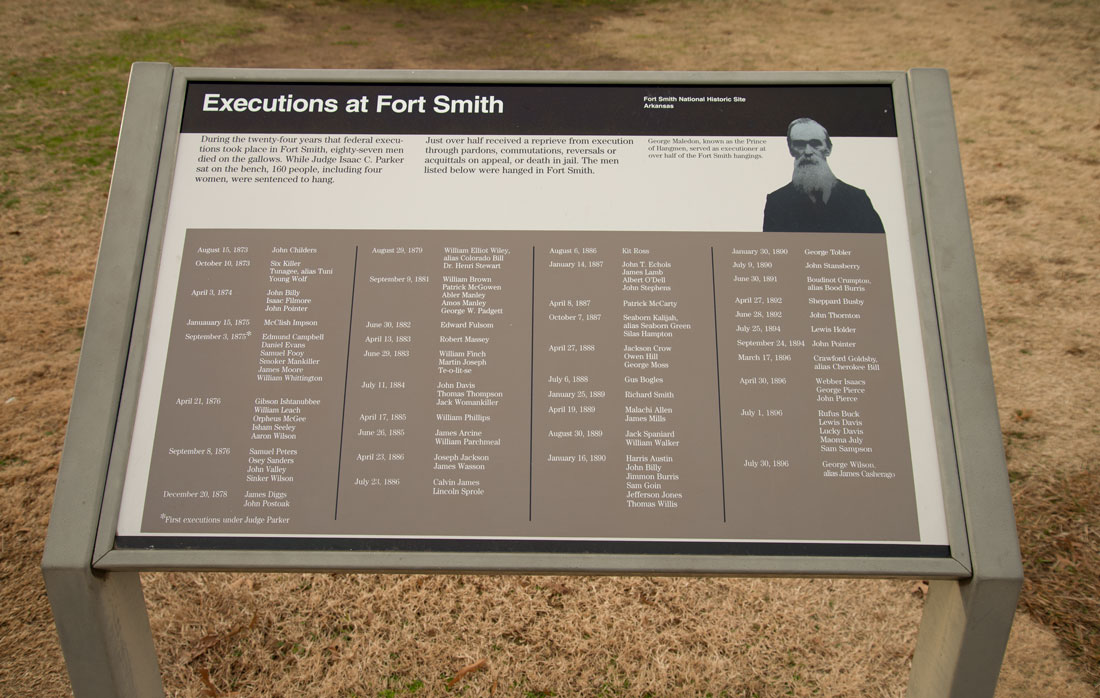

Those who were caught and incarcerated at Fort Smith faced Federal Judge Isaac C. Parker, called the “Hanging Judge” because he sent 79 offenders to the gallows. He was a staunch defender of Native American rights and law and order in Indian Territory. More people were put to death for crimes at Fort Smith than at any other place in U.S. territory. The fort prison was called “hell on the border.”

The Fort Smith gallows and, below, the notorious jail.

The list of executions carried out at Fort Smith.

Many Native Americans settled in the Fort Smith, Arkansas, area.

After the Civil War, the U.S. government required the Cherokee Nation to sign a new treaty because it had allied with the Confederacy. Cherokee slaves were freed, and those who continued to reside within tribal lands were granted all of the rights and citizenship of native Cherokees. A number of Civil War battlefields were on what was once Cherokee land, a history which is often obscured at these sites in favor of Civil War-era interpretation for visitors.

The US government acquired easement rights in Indian Territory for the construction of railroads, which brought white settlers. The Dawes Act of 1887 provided for the breakup of commonly held tribal land into individual household allotments. The U.S. government counted the remainder of tribal land as "surplus" and sold it to non-Cherokees. The Curtis Act of 1898 dismantled tribal governments, courts, schools, and other civic institutions.

In the late 19th century, Jim Crow laws in North Carolina and other southern states classified Native Americans as “colored” and they suffered the same racial segregation and disenfranchisement as African Americans did. Their constitutional rights as U.S. citizens were not enforced until after the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-1960s. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the Cherokee Nation ratified a new constitution and got federal recognition.

Today, the Cherokee Nation has substantial business, corporate, real estate, and agricultural interests. It is a large defense contractor in eastern Oklahoma and builds health clinics, roads, bridges, educational facilities and other projects in eastern Oklahoma.

The Cherokee Nation hosts the Cherokee National Holiday on Labor Day weekend each year, publishes a tribal newspaper in both English and Cherokee, and is involved in preserving Cherokee culture. The tribe supports the Cherokee Nation Film festivals in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, and participates in the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

The Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians in North Carolina hosts more than a million visitors a year at cultural attractions. It also runs the foremost Native American craft cooperative, Harrah’s Cherokee Casino and Hotel, a hospital and other organizations.

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians formed a government under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and gained federal recognition in 1946. Many of its members are descended from Cherokees who moved to Arkansas and Indian Territory before the Trail of Tears. This band operates many businesses.

The tribes cooperate with each other in a number of cultural exchanges and other programs but also have had disagreements over the years.

Cherokees today are mostly concentrated in Oklahoma and North Carolina, but some groups live in Western states.

The various Cherokee tribes have different membership rules.The Cherokee Nation determines enrollment by lineal descent from Cherokees listed on the Dawes Rolls and has no minimum blood requirement. It includes many mixed race members. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians requires a minimum one-sixteenth Cherokee blood, equivalent to one great-great-grandparent, and an ancestor on the Baker Roll. The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians has a quarter blood requirement. The 2000 federal census reported 875,000 people who identified as Cherokee, but only 316,000 people are enrolled as citizens of the federally recognized Cherokee tribes. There also are 200 Cherokee Heritage Groups, although the claims of some are controversial. The Texas Cherokee whose ancestors migrated to Texas is one such remnant group.

The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail is run by the National Park Service. Parts of it can be followed on foot or by horse, bicycle or car.

Here are some of the major Trail of Tears sites:

North Carolina

Museum of the Cherokee Indian – Cherokee, North Carolina.

Great Smoky Mountain National Park – Oconaluftee Visitor Center – Cherokee, North Carolina.

Junaluska Memorial and Museum

Cherokee County Historical Museum – Murphy, NC. This was the site of Fort Butler, one of the main holding areas for Cherokees removed from North Carolina in the 1830’s.

Tennessee

Sequoyah Birthplace Museum – Vonore, Tennessee.

Cherokee Removal Historic Park – Birchwood, Tennesee. This park is dedicated to those who died and made the trek along the Trail of Tears and to educate the public about the migration. Cherokees camped at the site before taking a ferry west. A visitor’s center includes a library for Native American history and local history. The library assists visitors in tracing their Cherokee ancestry. A memorial wall is planned that will contain the names of 2535 heads of household from the 1835 census of the Cherokee Nation that was taken to identify those to be removed. The census showed that they were farmers, mechanics, weavers and businessmen and many were literate in both Cherokee and English. The sunken flow of an outside amphitheater shows the water and land routes taken by the Cherokees to the West. Hiwasee Island in this area was a Cherokee site where Sam Houston lived and was adopted by Chief John Jolly.

Hiwassee River Heritage Center – Charleston, Tennessee. Charleston was the site of the federal Indian Agency and U.S. military headquarters for the Cherokee Trail of Tears removal. About 9,000 Cherokee, 600 Creek and 300 enslaved people were forcibly gathered there and removed along the Trail of Tears. There are a number of Cherokee historical sites in the area, including places where prominent Cherokee leaders lived.

Red Clay State Historic Park – This park includes a historic Cherokee farmhouse, cabins and a council house as well as an interpretive center.

Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage – Hermitage, Tennessee. This is the home of U.S. President Andrew Jackson, who supported the removal of Native Americans to the West.

Georgia

Chief Vann House State Historic Site – Chatsworth, Georgia – This plantation house and grounds were owned by wealthy Cherokee leader James Vann and his son Joseph Vann. It was the largest and most prosperous plantation in the Cherokee Nation. During the Indian removal, the Vann family lost the home.

Funk Heritage Center at Reinhardt University – Waleska, Georgia. This center tells the story of Southeastern Indians and early settlers and has a contemporary Native American art gallery.

Chieftains Museum Major Ridge Home, Rome, Georgia – This was the home of prominent Cherokee Major Ridge, whose story is preserved and interpreted at the home/museum.

Alabama

Russell Cave National Monument – This is an archeological site with one of the most complete records of prehistoric cultures in the Southeastern United States. Some of the artifacts represent more than 10,000 years of human life in a single place.

Missouri

Snelson-Brinker House, west of Steelville, Missouri. This was an overnight stopping point on the Cherokee Trail of Tears.

Trail of Tears State Park Visitor Center – Moccasin Springs, Jackson, Missouri. Nine of the 13 Cherokee groups relocated to Oklahoma crossed the Mississippi River here during harsh winter conditions in 1838-39. The visitor center tells their story.

History Museum on the Square – Springfield, Missouri. This regional history museum has a gallery about Native American history.

Kentucky

Trail of Tears Commemorative Park – Hopkinsville, Kentucky. This was a campsite used during the Trail of Tears and is the burial site for two Cherokee chiefs who died during the removal. An intertribal Pow Wow is held at the park annually on the first weekend after Labor Day.

Arkansas

Delta Cultural Center’s Depot Museum – Helena, Arkansas. This regional museum includes an exhibit on Native American life on the Arkansas Delta.

Fort Smith National Historic Site - Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Cedron Settlement Park, Conway , Arkansas. This is a living history site for a community that included Native Americans.

Museum of Native American History, Bentonville, Arkansas. This museum covers 14,000 years of Native American history.

Oklahoma

Cherokee Heritage Center, Tahlequah, Oklahoma. This center includes a 1710 Cherokee village, demonstrations of cultural practices, and a Cherokee village of the 1890s as well as a Trail of Tears exhibit and a Cherokee family history research center.

Hunter’s Home, Park Hill, Oklahoma. This Cherokee plantation is the only remaining pre-Civil War plantation home in Oklahoma. It is a living history site. It was owned by the Ross family, which built it after they were forced to leave their homes during the Trail of Tears.

Webber Falls Museum - Webber Falls, Oklahoma. This museum tells the story of Cherokees who played an important role in the settlement of Webber Falls.

Check out these related items

La Purisima Mission

The history of La Purisima Mission in Lompoc, California, is a cautionary tale about the consequences of environmental damage, epidemics and racial inequality.

Mountain Men and the Fur Trade

The colorful annual mountain men rendezvous at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, commemorates the 19th century global fur trade.

Reconstructing the Story of an Ancient Civilization

Researchers are piecing together an ever-clearer picture of the ancient civilization of the American Southwest called the Ancestral Puebloans.

The Land of Junipero Serra

Junipero Serra's "sainthood" is controversial, but the extent of his cultural impact on California is indisputable.

What does it mean to be Hispanic?

What does it mean to be Latino or Hispanic in the United States? This blog explores the ambiguous origins of these two terms.

The History of Race in America

The racial history of the United States belongs to us all, with the responsibility to resolve the accompanying outstanding problems.