The Psychology of Strongmen

Photos by Forrest Anderson

We live in an era of strongmen rulers who see themselves as the saviors of their nations while denying their people the protection of democracy and truth.

As international journalists, my husband and I observed strongmen rulers at close range, witnessing their leadership style at many diplomatic visits, government meetings and in national and international crises. We also saw the results of their behavior on their nations’ citizens.

Here is what we learned about the psychology of strongmen:

What are strongmen?

Strongmen leaders promise to deliver law, order and prosperity, but legitimize the breaking of both domestic and international laws and norms to meet their personal aims. Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is just the latest of a long line of strongmen aggression and violence that has devastated countries around the globe at one time or another.

Because strongmen are narcissistic and psychopathic, they are drawn to power, skilled at getting it and destructive at wielding it. They are good at manipulating people because they possess superficial charm and charisma that enables them to get people to flock to them in the short term. Such traits serve them well in getting elected or moving up in political and military hierarchies. However, their behavior is a performance rather than an actual manifestation of empathy for their people and their problems.

Putin and other strongmen use propaganda, cronyism, and police crackdowns to retain and expand their holds on power. From Putin to Chinese leader Xi Jinping and back in history to Napoleon Bonaparte in France, Henry VIII in England and countless other strongman leaders in many countries, their style of leadership brings with it destruction of peace, legal constraints and repression of citizens’ rights.

Such leaders prioritize their own self-interest over the public good, while conflating the two. Strongmen use nationalist myths of greatness to build support for themselves.

Napoleon believed that he was the embodiment of France, and other strongmen typically believe the same about their relationship to their nations. They preach that their views represent what is good for their nation, but their blindness to dissenting public opinion causes them to fail to get the results that their people need in turbulent times.

Strongmen are typically supported by followers who have authoritarian charactistics, but strongmen go far beyond authoritarianism. Studies indicate that authoritarians, who represent a minority but still a substantial proportion of society, tend to prioritize order, social conformity, tradition and security. Ordinarily, they are upholders of law. When pushed to extremes, however, they tend to support anti-democratic measures such as martial law, violence for political reasons, and strongman leadership.

However, authoritarians aren’t the most fervent supporters of strongmen. Their strongest supporters are those, who unlike typical authoritarians, have a disregard for social and legal norms. These people normally are not politically involved, but they are drawn to strongmen who have manufactured larger-than-life public personas that include flaunting a disdain for normal civil interaction.

Strongmen exaggerate these people’s threats to spark fear in them that triggers both anger and acquiescence to strongman policies. This makes this segment of society a mobilizing force to gain support from others in bringing strongmen to power.

What Happens When Strongmen Get Into Power?

Once strongmen are in power, their followers become beholden to them for their positions all up and down vertical hierarchies of parties and governments. Many of these followers stick with strongmen well past the point where their policies have proven to be ineffective. They do so because they don’t want to admit that they were wrong. The reasons for this reluctance are not just pride, but career and financial consequences, concerns about losing their own power, or concerns about their own and their families’ safety if they switch loyalties. Strongmen provide powerful elites with perks upon which they become dependent over time as they lose their grip on their independence.

There is a Stockholm Syndrome aspect to the psychology of strongmen. They have a constant need to humiliate and control others, and continue to hold on to power so that they can do so. In some cases, such in North Korea, this can go on for generations as strongmen build political dynasties for their children or followers to succeed them. In the process, any democratic institutions that ever existed are dismantled or coopted in service of the dynasty.

Strongmen throughout history have manipulated entire political, religious and social systems to suit their own aims.

King Henry VIII of England was an example of a strongman who cast aside the legal, social and religious norms of his day to meet his own aims. Above, the site at the Tower of London where he had his wife, Anne Boleyn, executed. He started the Church of England to justify his sidelining his wife and marrying Anne, but then eliminated her to pursue another woman.

Strongmen typically meddle in voting and engineer the abolition of term limits in democratic countries because once they become unpopular, they need to manipulate elections to retain power. Putin, Xi, and other historical figures such as Napoleon are prime examples.

Along with this behavior comes a disdain for the truth. Strongmen take advantage of public vulnerability to misinformation to spread and exaggerate lies about threats.

Internationally, strongmen often take the side of other strongmen leaders, especially in foreign military aggression or crackdowns on human rights activists. Interestingly, they often support other strongmen even when those leaders nominally are on the opposite end of the political spectrum.

Why do Strongmen Appear on Both the Right and Left?

Support for strongmen can cross educational, income, class, and religious lines. It occurs on the political right and left.

Why is this? Social scientists have studied this question since Adolph Hitler rose to power in Germany. Researchers have reached the conclusion that people who have a tendency toward authoritarianism turn when threatened to strongman leaders who promise to take action to protect them from outsiders and to prevent frightening social, political, or economic changes. This phenomenon can occur on either the left and right.

In such circumstances, moderation and nuance drop away as people who are not personally extreme migrate toward strongmen leaders who promise to use force to alleviate their fears. Such leaders go far beyond acceptable norms to do so.

Once a strongman leader is in power, his policies breed strongmen who do the same at every level of society. This destroys moderate civil norms in all levels of political life as leaders with extreme political views gain power on promises of bringing control and security.

Why do Strongmen Appeal To Some People?

It takes a combination of demographic, economic, and political change to cause people to rally around strongmen. Studies indicate that authoritarianism can be measured by how highly people value hierarchy, order, and conformity over other values such as independent thinking.

Those studies also have shown that most people don’t support extreme policies out of a desire for authoritarianism, but as a response to threats such as terrorism or eroding social norms. Faced with these threats, even non-authoritarians will move in the direction of supporting strongmen who promise to eliminate the dangers. When multiple threats appear simultaneously, this tendency can quickly intensify.

Authoritarians are more prone than non-authoritarians to reject people who are perceived as outsiders, but specific groups of people labeled as outsiders can change depending on how they are manipulated by strongmen and depending on their connection to foreign threats. Fears of people perceived as outsiders can change as events make different groups seem more or less threatening.

This plays into the hands of strongmen, who often demonize ethnic groups as the purported source of problems. Strongmen tend to reduce all issues to extremes of greatest and worst and to claim that difficult problems haven’t been solved because other politicians are weak. Strongmen often label civilized, inclusive negotiation as weak.

This extreme authoritarianism is hostile to democracy because in a democratic society, people are willing to work together and compromise on difficult topics on an on-going basis despite their inability to reach a consensus on some issues. This is why strongmen rarely win national elections in very pluralistic and ethnically diverse countries.

When confronted with perceived threats to the status quo, disparate groups of authoritarians can band together to support a strongman leader. This is especially true when they lose long-standing privileged positions or are faced with loss of jobs and economic downturns.

People who support strongman leadership also tend to support military action, cracking down on immigration, and limiting civil liberties when faced with foreign threats. They become willing to change their national consitutions and impose police surveillance on the public to support a strongman’s agenda.

Strongmen have been on the rise across the globe in recent years, with some countries adopting dictatorships and an authoritarian right gaining popularity in countries such as Hungary, Austria, Italy, the Philippines, Thailand, and other nations. Some expert observers believe that this is because of unsettling changes in social norms around gender, sexuality, and race as well as economic disruptions, the pandemic, and climate change.

Many observers had assumed that information and technology revolution would work against strongmen by holding them accountable for their misconduct. However, strongmen are using technology to tighten control over the use of data, expand political surveillance and control, and spread misinformation.

The Downside of Being a Strongman

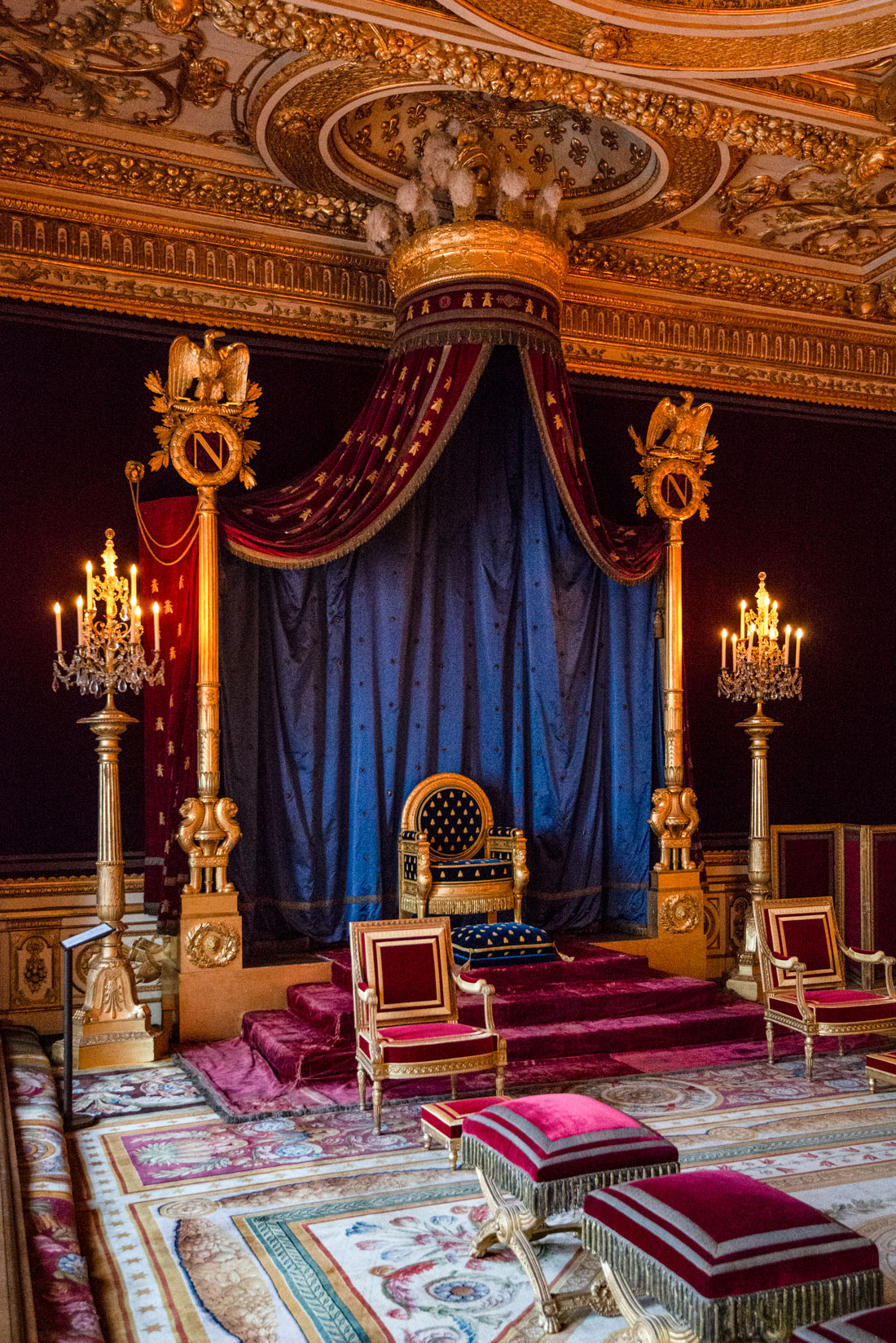

Many strongmen enjoy the pomp of being a leader more than the actual governing. Under them, the appearance of power becomes a high priority, robbing their subjects of good governance. Above, a throne room at the Palace of Fontainebleau, France. The pomp and circumstance of strongman leadership reached a height under French kings, to the point where it overtook and consumed governing as the kings' major activity.

Strongman leaders lack an off-ramp from power when they get to the point where most of their subjects are disillusioned with their propaganda. They fear loss of power not only as the destruction of their own self-image, but also because they fear retribution for their aggressive acts while in office. Many have family members who were complicit in those acts, and the strongmen try to protect them by staying in office.

Over generations, strongman governance can concentrate power in one individual whose political and financial interests and relationships with other despots and oligarchs who contribute financing often prevail over national interests in shaping domestic and foreign policy. This type of system once was entrenched in Europe by marital alliances between monarchies. Kings would weigh in on the side of their cousins or siblings who ruled other countries even when such alliances acted against the wishes and interests of their own subjects. One of the most well-known examples of such networks was the absolute power of France's kings in the 17th and 18th centuries, which ended badly with the French Revolution.

A gate at the Palace of Versailles, where French kings lived, governed, and tightly controlled the country's aristocratic elites.

Today, Putin’s close ties with oligarchs who have international financial interests are an example of this type of network. Chinese leaders, despite their official non-interference foreign policy stance, have cultivated close ties with other autocrats such as Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. Strongmen seek out other strongmen who legitimize their worldview. They tend to take it personally when such allies are deposed, fearing that the movements which have overthrown them can spread to their own lands.

Strongman rulers are constantly pursued by fear. They view criticism of their policies as plots targeting them. They intimidate and buy off not just their own nation’s elites, but also weaker neighboring nations whose financial structure and even entire region become dependent on strongman patronage. This makes it hard to for these entities to pull themselves loose from strongmen who don’t deliver on results.

Strongmen are shielded from unwelcome realities because their inner circle is flatterers who report only what the strongmen want to hear. Strongmen live with their families in privileged compounds, supplied with luxuries and privileges that can make them unaware that their subjects lack even necessities. Deng Rong, the daughter of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, wrote of her shock at experiencing the living conditions of ordinary Chinese when after having been raised in the compound where China's highest leaders live, her family was for a time disgraced and expelled by Chinese strongman Mao Tse-tung.

Deng bounced back and rose to become China's top leader after Mao's death. Deng also was capable of strongman behavior, including the 1989 crackdown on pro-democracy protesters at Tiananmen Square, suppression of intellectuals, and tight control of the press, but there is no doubt that his experiences under Mao had a moderating effect on his rule.

When strongmen go out in public, they are surrounded by entourages of adoring leaders whose job it is to carry out their policies. Strongmen inflate the number of people who they think believe their propaganda. Many strongmen come to believe that they are stronger than they are. An example is Italian strongman Benito Mussolini, who disastrously miscalculated in allying with Adolph Hitler in World War II.

Strongmen surround themselves with orchestrated state ideologies that are propagated with religious fanaticism to the exclusion of dissenting viewpoints. Strongmen either squelch or coopt and then dilute other views, limiting the scope of public discourse.

Strongmen are protected from the results of their failed policies in societies in which they control the press, limit discourse on social media, and limit public assembly. When it dawns on them that their popularity is declining, they blame close supporters for the messes that their policies have made.

Strongmen can be particularly dangerous when their power is threatened. Putin’s threat to use nuclear weapons during the Ukraine crisis is one example of such sabor rattling. They can hold the world hostage with such extreme threats.

They refuse to accept defeat or responsibility. Even in exile, they continue, as Napoleon did, to believe that their former subjects will rise up and demand their return. Napoleon was called General Bonaparte by his British jailers after he was exiled from France, but he constantly insisted that he continue to be called Emperor Napoleon.

Strongmen create cults of personality around them that become the legendary cultures of entire eras and bleed into future eras. In China, the country's most destructive strongman ever, Mao Tse-tung, lives on in propaganda that compares current leader Xi Jinping to him whenever the Communist Party propaganda machine wants to show Xi as a strong leader. This happens although China was in a shambles by the time Mao died in 1976, and his successors immediately acted to dismantle his policies.

A statue of Mao, with a portrait of Russian strongman Joseph Stalin behind him, Military Museum, Beijing, China. Mao was an admirer of Stalin.

Xi has skillfully blended his own traumatic 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution youth with what he calls the Chinese Dream and the Chinese Communist Party’s exclusive claim to authority. He has concentrated power and support for himself into China’s leading bodies to the point that Xi Jinping Thought was enshrined in China’s constitution in 2017 and term limits were abolished to allow him to stay in power beyond his ten-year term. This has all been done on the model of the cult of personality that once surrounded Mao.

The cult of personality around Xi is propagated in pop songs, music videos, extravaganzas, books, constant newspaper reports, and a mobile app for studying Xi Jinping Thought called Xuexi Qiangguo. It is claimed to be the most downloaded app on Apple’s App Store in China. Xuexi is a pun, since the word can mean both “learning” and “Learn from Xi.”

Do Strongmen Ever Die?

“Death is the solution to all problems. No man – no problem,” said Soviet strongman Joseph Stalin.

Would that he had told the truth. Strongmen can be resilient, even long after their deaths. More than a million people, both French and foreign, annually visit Napoleon Bonaparte’s sarcophagus at Les Invalides in Paris although he was only in office for about 11 years and died two centuries ago. There still are fierce debates about whether he was a hero or a tyrant.

This driven figure fit the strongman personality to a T. He was controlling, self-serving, greedy, and unscrupulous, with little empathy for others. His delusional vision still marks parts of Paris today. His was a typical example of a strongman strategy that failed to work in the long run. Today, however, he still is periodically trotted out as an example of a great Frenchman.

He's not alone. Long-dead strongmen continue to capture the imagination and to act as models for current tyrannical leaders throughout the world.

Mao Tse-tung was an admirer of the ancient Chinese emperor Qin Shihuang, depicted as a wax figure in a display in Beijing, China, above Mao modeled himself on Qin in many ways despite Qin's reputation for extreme cruelty. Napoleon did the same with the Caesars who rule Rome, seeing himself as an heir to the Roman imperial tradition.

Check out these related items

Dawning of a New Era of Diversity?

Despite dismal headlines about the racial divisiveness of the United States, several long-term trends point to a future more mature culture of diversity and cooperation.

A Tale of Two Roman Cities

The amphitheaters, military garrisons, forums, trade and craft shops of two Roman colonial cities have emerged from the dust.

The Tower of London

The Tower of London, enduring symbol of the British monarchy, combines royal pageantry with warfare, court intrigue and executions.

Tiananmen Square

China's Oct. 1 celebration of 70 years of Communist rule centers on Tiananmen Square, one of the world’s most controversial places.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

Versailles’ Checkered Legacy

Versailles has an image of lavish opulence under the Sun King, Louis XIV, but the palace also has a history of revolution and American ties.