Private Paradises Amid Adversity

When we worked as journalists in China in the late 1980s and 1990s, the country was still emerging from the disaster of the Mao era. Beijing, where we lived, was a grimy, crowded and poverty-stricken industrial city with too many people chasing too few jobs. Most people had assigned jobs in spartan factories that paid them almost nothing but controlled every aspect of their lives. At home, they lived in tiny, crowded rooms with few amenities.

I spent a great deal of time wondering how people could endure the lack of privacy, constant government intrusion in their lives and uncertainty of an rapidly transforming economy. After many conversations with Chinese from all walks of life, I realized that many remained sane and some were thriving because they had carved out small private paradises – hobbies, interests, and special places – to which they regularly retreated. One man grew miniature living landscapes in tiny Yixing teapots. Others painted versions of famous Chinese paintings, played the piano or another instrument, practiced calligraphy or browsed through bookstores for old books. Some were skilled craftsmen at traditional arts while others sang Italian opera. Some toured local historical sites and wrote about them. Others grew exotic flowering plants in their tiny courtyards or on their balconies. Some became expert cooks in some aspect of Chinese cuisine. Many of them banded together in support groups of like-minded enthusiasts. They were passionate about these creative pursuits, which helped keep them grounded during the social and economic upheaval that transformed China into a modern nation.

As time wore on, many of these people developed their private hobbies further, launching businesses around their interests that transformed them into prosperous businesspeople. Collectively, their creative efforts became the most dynamic part of the Chinese economy and helped transform it.

This couple in central China, who were among the first wave of prosperous private business people in China during this era, turned their private hobby of bonzai trees into a prosperous business that lifeted them out of poverty. Photo by Forrest Anderson.

The subject of secret paradises in the midst of uncertain, frightening wider circumstances has fascinated me ever since. I have since discovered this healing phenomena in other cultures that have long been plagued by upheaval and constraints. In some of these cultures, such as Japan’s, the ability to find private paradises in difficult circumstances has become a major part of the national culture and psyche.

During the coronavirus which has kept more people at home, many people have retreated into these private creative worlds. The resulting outburst of creativity, which has flooded social media, has revived my interest in the phenomena of private paradises amidst hellish circumstances.

This blog is an attempt to examine the role of personal creativity in adverse circumstances. Why do some people thrive because of their private interests, even leveraging them to mitigate or eliminate adversity? As we all look for a way out of the pandemic and its accompanying economic fallout, such questions have become critical.

Many psychological studies indicate that personal creativity plays a key role in determining our ability to thrive in tough times. Adversity can be devastating, but it also can be accompanied and followed by positive psychological growth. There is such an intimate connection between creativity and adversity that the theme of art born of adversity is almost a cliché in the lives of the world’s most eminent creatives.

Much of the music we listen to, plays and films we see and paintings we look at are attempts to find meaning in human suffering. Art is part of the process of making sense of both small and earth-shattering moments of sadness. Creative people who have struggled with illnesses, loss of loved ones, social rejection, abuse and other trauma often use art to turn their challenges into opportunity. This becomes a habit that accompanies and helps them through life.

When we turn to creative outlets in times of adversity and then share the art we create, other people know they aren’t alone in their struggle for meaning. As Victor Frankl wrote, “In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning."

As many people wonder what kind of life we will have when the pandemic subsides, scientific evidence suggests that we will recover and be more resilient and capable of growth. Resilience, clinical psychologist George Bonanno said, is the ability of people who have experienced a highly life-threatening or traumatic event to maintain relatively stable, healthy levels of psychological and physical functioning.

Bonanno’s research has shown that about 61 percent of men and 51 percent of women in the United States have experienced trauma such being diagnosed with a chronic or terminal illness, losing a loved one or being assaulted. The majority don’t develop post-traumatic stress disorders and many report that they experienced post-traumatic growth.

This growth comes in seven areas - greater appreciation of life, greater appreciation and strengthening of close relationships, increased compassion and altruism, identification of new possibilities or a purpose in life, greater awareness and use of personal strengths, enhanced spiritual development and creative growth. These people acknowledge this growth although most say they still wish the traumatic event had never happened. They are often surprised by the growth.

Trauma forces us to look anew at our goals and dreams. Our assumptions about living in a benevolent, controllable world are shattered and we are forced to rebuild ourselves amid uncontrollable realities that we would prefer to ignore. We can’t change the overall situation, so we have to change ourselves to cope. This becomes the basis of new growth because we have to become open to new opportunities. This is the beginning of creativity.

Bread at the famous Poilâne bakery in Paris, France. Apollonia Poilâne helped propel the bakery into one of the world's premier bread producers when she inherited it after her parents were killed in a plane accident when she was a college student. Her story is proof that creativity and excellence in adversity can revolve around something as simple as a loaf of bread. Photo by Forrest Anderson.

Polish psychiatrist Kazimierz Dabrowski concluded that healthy personality development requires some personal disintegration, which can temporarily lead to self-doubt, anxiety, and depression but also a deeper examination of what we can become. This then leads to higher levels of personal development.

A key factor in turning adversity to our advantage is the extent to which we fully explore our thoughts and feelings about an event or trauma. This exploration gives us a curiosity about confusing situations which increases the likelihood that we will find new meaning and solutions in them. We are forced to shed our defense mechanisms and confront the discomfort head on to lead to a more nuanced view of reality.

Clotilde Bizolon was one of the inspirations behind the famous Les Halles gourmet food market in Lyon, France, considered one of the finest food markets in Europe. Bizolon began her career by offering her homemade foods to soldiers at the Perrache train station in Lyon during World War I. Other people followed suit and the eventual result was Les Halles, where food by famous chefs is offered for sale. Photo by Forrest Anderson.

The way this works is that in the beginning, we tend to stew over the trauma constantly, trying to make sense of it as it tears down our old belief structures and creates new ones of meaning and identity. Our thinking eventually becomes more organized, controlled and deliberate during this excruciating process. It enables us to tap into deep reservoirs of strength that we were unaware we had.

On the other hand, if we try to avoid our sad, angry, anxious thoughts, we can paradoxically make them worse because they reinforce the belief that the world is unsafe. This makes it more difficult for us to pursue strategies that can make the world safer and meaningful again in the midst of adversity. When we face the world as it is with openness, we are better able to react to events based on our chosen values.

Chinese artist Fang Lijun and one of his famous paintings. Fang and a group of other young artists carved out a creative space for themselves in an artists' colony in the turbulent late 1980s in Beijing, China, when artists were emerging from a dark period of political persecution. Fang used the metaphor of baldness, traditionally an object of derision in China, to send the message that artists are not eccentric outcasts but just people who are creating change. This photo is consistently one of the most loved on our Pinterest boards, having been repinned thousands of times. Photo by Forrest Anderson.

Researchers have found that people experience greater post-traumatic growth and less anxiety if they don’t avoid the issue of the trauma. Deliberately thinking through or ruminating about a trauma leads to the post-traumatic growth mentioned above. This growth is associated with creativity.

In many cases, famous artists’ physical illnesses or other trials have forced them to break old habits and come up with alternative strategies to reach their creative goals. Studies have shown a high preponderance of harsh early life events among eminent creators.

Research supports the immense benefit of engaging in art, writing and other creative pursuits to rebuild after trauma. This seems paradoxical because many people experience a decline in their perception of new possibilities for their lives as a result of adversity. However, this often leads to them being more open to new experiences, a factor which is closely related to creative engagement and achievement. Trauma survivors think more creatively about future opportunities.

Even among severely traumatized patients, such as some Rwandans exposed to the 1994 genocide, about 25 percent of people in one study reported moderate increases in creativity after the experience.

The results don’t suggest that adversity is necessary for creativity, as many other things can broaden our minds, inspire and motivate us. They do indicate that many people who have experienced traumatic events have the power to use them to heal, grow and flourish creatively.

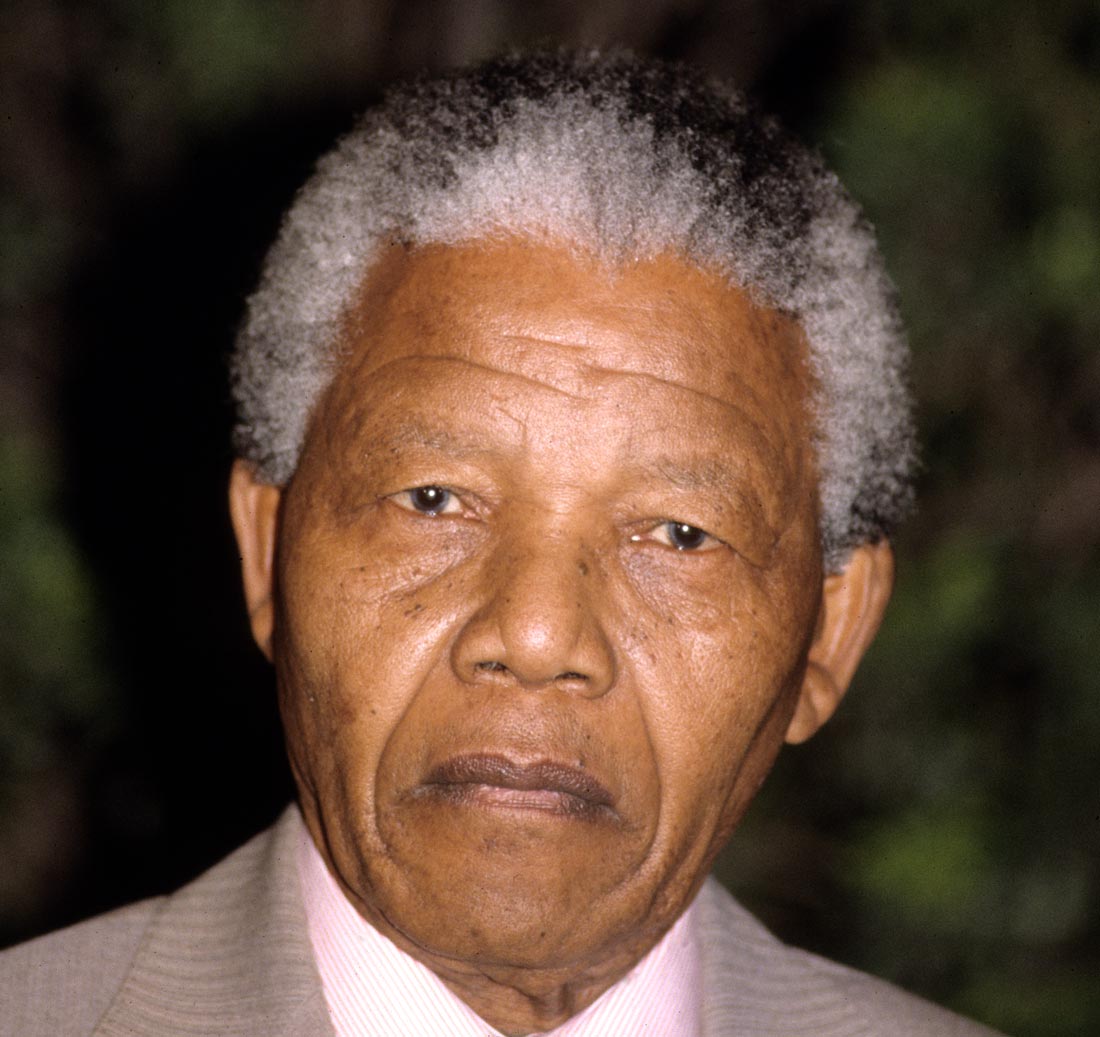

Nelson Mandela spent 27 years in harsh, damp prison cells, including many periods in solitary confinement, for his opposition to apartheid in South Africa. During those years, he engaged in a variety of creative pursuits - working at night on a law degree after spending his days in forced labor, writing his autobiography, gardening and studying Christianity and Islam. He initiated a university among the inmates in which they lectured to each other on their various areas of expertise. Photo by Forrest Anderson.

There is evidence that engaging in creative pursuits is often associated with increased resilience and adaptability, as it brings feelings of power, pleasure, meaning, purpose, a heightened awareness of skills, setting and achieving goals and focusing on and meeting challenges. Creativity also helps people to acquire skills, receive feedback and give their undivided concentration to creative activities which are an end in themselves. It helps people shift their attention from external to internal stimulation, which is psychologically healthy. It stimulates the imagination. This doesn’t mean many creative people don’t experience high anxiety and depression. Many do. However, those who have experienced traumatic events tend to be more aware of a loss of sense of self, have a greater sense of contact with a force beyond themselves, have greater emotional intensity that coexists with emotional stability and have a heightened awareness of their technical and expressive abilities and increased spiritual awareness during the creative process. They are better able to be receptive to art and to move between being absorbed in it and distancing themselves from it to critique it. They have greater appreciation for the transformational quality of creativity.

Debbie Chou Robins' garden room, and, below, her outdoor Japanese garden. Gardening is a common focus of creativity in adversity. Photos by Joe Robins.

Creativity helps us cope with the world and gives us ways to deal with the complex problems that confront us. It also gives us the capacity to empathize and connect with others in creative ways.

We are seeing an increase of everyday creativity as many who are working from home have more time on their hands. For many, creativity is small, insightful moments. They may not be important to others or even shared with them, but they still are important to the creator. If people continue to be interested in and enjoy them, they eventually share them and get feedback. With enough time, practice, focus and improvement, they can advance to expert level. Sometimes they eventually publish a book, start a business, get a grant to study their topic or record their first album. They have become an expert whose efforts are appreciated by other experts or a stand-out whose works shake up their field. If they continue to progress and become a genius in their field, their work will outlive them and influence their field for generations.

Gullah sweetgrass baskets, one of the specialty artworks of South Carolina, are an art form that began among slaves imported from Africa to the Carolinas. For 350 years, they have passed their basket weaving skills down to their descendants. The baskets have become highly prized symbols of resilience and family ties amid adversity. Photo by Forrest Anderson.

The outburst of creativity during the pandemic will help shape our post-pandemic world as it helps us personally to work through the problems we are facing because of the crisis. People tend to think that constraints stifle creativity, but studies have found that they have the opposite effect. When people lack time, money or process constraints, they often become complacent and follow the path of least resistance. In those situations, they go for the first idea that comes to mind and don’t invest in developing better ideas. Constraints remove the most obvious solutions, so we are forced to search for other better ways to solve problems.

According to one study, boredom also helps spark creativity because it is uncomfortable and motivates people to search for something to alleviate it.

Our new normal is a massive constriction of daily routines and social interaction, freedom of movement, and space. This has intensified the search for solutions to our problems. The pandemic has highlighted the growing need for creativity to limit the spread of the virus, develop a vaccine, teach children while schools are closed, and solve the massive economic problems that the pandemic has caused. The need to solve these problems is the new normal. People are confronted with a stream of unknown, unexpected, and unpredictable situations. Our ability to think and act creatively is more important than ever.

The basic components of creativity are projects, passion (working on projects we care about), persisting with them in the face of difficulties, working and learning with others, and play (experimenting, trying new things, taking risks and testing the boundaries).

Creativity means that we are not defined by the disasters that befall us but by the positive content of our lives. Even our small creative projects have a role to play. In creativity is where we find our best selves, because in creativity we have an impulse to share and to solve problems.

With more time to ourselves and online classes, we can participate in creativity. We are witnessing examples of participatory creative experiences on a huge scale. This creativity is helping us cope with the present and create a bridge to the future. It gives us the chance to ask how the world should be different when the pandemic is over.

Many of us feel that we can’t influence the decisions of those in power, but creativity can help us to solve many problems that will shape our own future. We can think deeply and embrace new ideas that can help us find a way through this challenge. The pandemic invites us to tackle the uncertainty with innovation and creativity as the crisis threatens the ability of our public and business sectors to respond to the economic and health fallout.

We are becoming aware that the recovery will take years and leave seismic effects. It will test the extent to which our institutions can respond, but also can help us transition to more sustainable, mindful ways of consuming, producing and governing. It can transform the values and norms that shape our society. The uncertainty, complexity and scale of the pandemic means that we will have to iterate fast, accelerate learning and manage dynamically to build more resilient systems.

For many people creativity is a private refuge and therapy, but it can be used to heal not just ourselves but the world.

Creativity is like water. When faced with obstacles, it finds its way around them. In the process, it carves a new path. Many creative people say they are more prolific in creating artistic opportunities than they have been in years.

Extreme disasters tend to have extreme effects. For guidance on how this might play out for us, we can look to the black plague, which killed 30 to 50 percent of the population of Europe. It started in 1348 and moved fast, killing people within days of their developing symptoms. It spread through families, houses, villages, towns and cities with staggering death tolls. The tragedy transformed European society and the economy. The plague lasted for three years, emptying villages of inhabitants, leaving crops rotting in the fields and domestic animals starving. The labor force was wiped out in many areas, and aristocrats who provided the power structure died in droves. The economic system broke down. Without modern antibiotic treatment, 72-100 percent of those who contracted the plague died.

It was the beginning of an enormous economic and sociological shift. It took 200 years for Europe’s population levels to recover, during which the system of serfdom collapsed because labor costs went up. Ordinary people had more land, food and money.

This plague was followed by others, making periodic quarantines common. During one, Sir Isaac Newton famously retreated to his family home in Lincolnshire, England, where he laid the groundwork for his theories of gravity and optics and invented calculus. In London, theaters were closed whenever the death toll from plague was more than 30 per week. William Shakespeare wrote some of his best poems and plays during such a closure in 1606, including King Lear, Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra. Others such as the painter Edvard Munch and playwright Thomas Nashe were also productive during pandemics. Leonardo da Vinci came up with a series of urban plans during a bubonic plague that had spread in part because of poor urban planning. His solution was to move away from dirty, crowded, narrow streets to a more modern, clean, efficient layout.

We all know that it takes more than time off to do great work and many harried shelter-at-homers have pushed back strongly on social media at the notion that they should be writing a great play in addition to juggling kids and work at home during this stresseful time. The point, however, is not that we will all become Shakespeares in isolation. It is that if we personally and collectively are going to find a way out of our current dilemma, we need discipline, imagination and talent to do so. Many are finding that the pandemic is inspiring them to do the creative work that matters most to them. It is inaccurate to assume that there is a massive gap of some kind between us and famous people who chose to be creative in times of adversity. Newton, Da Vinci and Shakespeare were three men putting marks on paper during a pandemic, but what they chose to write and draw helped shape their future just as our personal creativity during this time is doing for us.

It’s worth considering that much of Europe’s greatest art and architecture was produced in the centuries between 1300 and 1700 when plague and quarantine were normal. This kind of creativity amid adversity is our cultural heritage. Our opportunity and challenge is for it to also become our future.

Saint Eustache Church, built between 1532 and 1632, Paris, France. Photo by Forrest Anderson.

Related photos:

Check out these related items

Home is Where the Vacation is

Vacationing at home looks to be the main travel trend for the near future. Here are some ways to enjoy it.

Home is a Destination, Too

Need a five-minute stress reliever while sheltering at home? See these photos of my beautiful mountain village of Mapleton, Utah.

Elements of a Japanese Garden

Imagine you're sitting in Los Angeles traffic on a hot day. Take a break and head for a cool green oasis - Suihoen Japanese Garden

Finding a Place to Call Home

It took four years to find a site for the Thoughtful House. Here's how we did it.

Meditation and Japan’s Rock Garden

Meditation is the theme of the Ryoanji dry rock garden. Find out why the garden inspires meditation and how to meditate.

Retreat by Design

What makes a retreat restful and soul restoring? A former imperial retreat in Kyoto, Japan, gets retreat design just right.