Confucius Conundrum

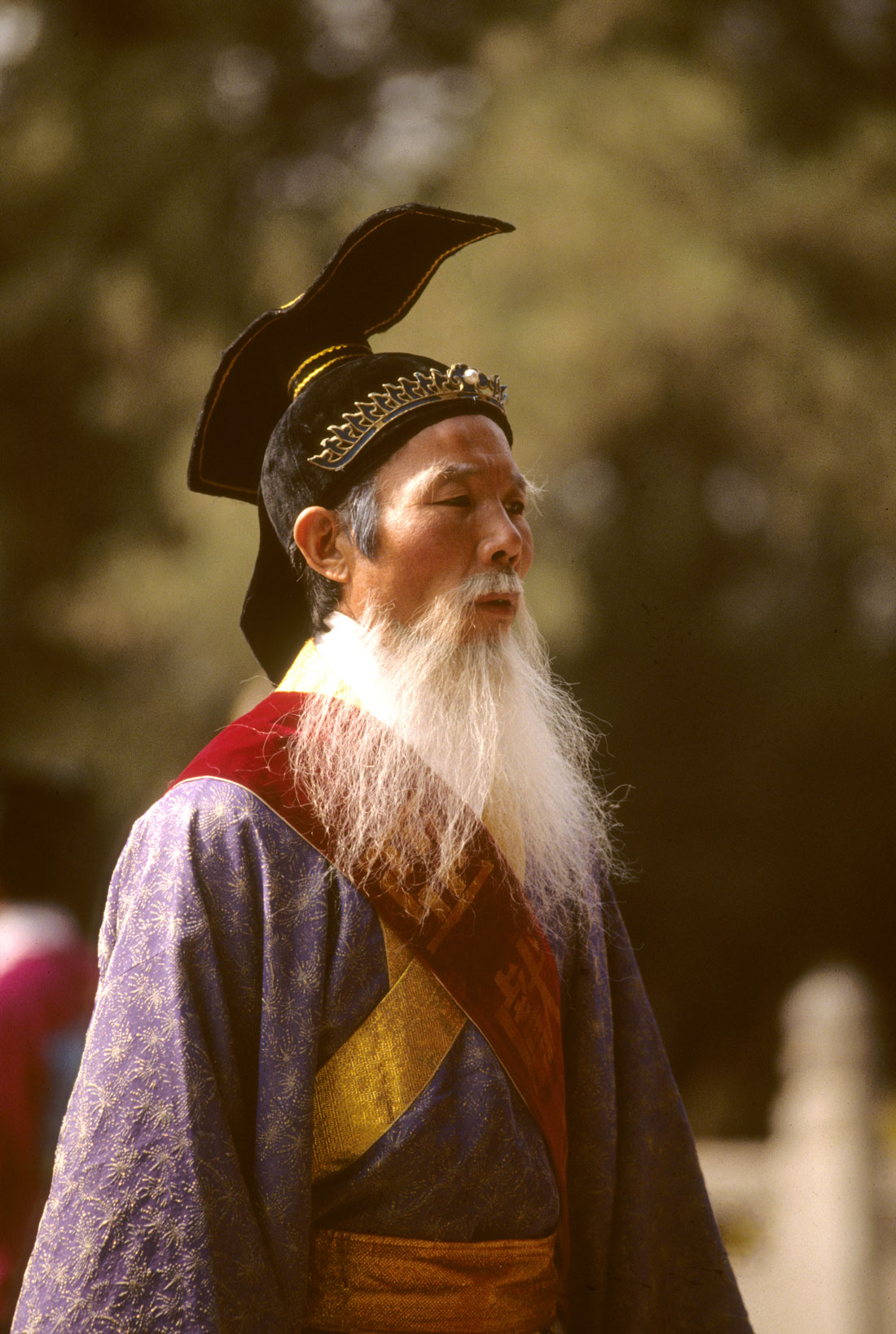

Photos by Forrest Anderson of ceremony for Confucius' birthday in Qufu, China.

The Chinese philosopher Confucius has been dead for about 2,500 years, but he still makes international news on a regular basis.

Lately, the ancient sage’s brand has taken a hit as universities around the world are closing Confucius Institutes that have been partially funded by China to promote Chinese culture and language.

Confucius is one of history’s most influential figures, but his image has ebbed and flowed over the centuries with various political winds. The current problem isn’t primarily with the philosopher himself or even the institutes that bear his name, but with the entity that has sponsored the institutes, the Chinese government.

Confucius Institutes were the brainchild of Chinese government officials seeking to extend Chinese soft power abroad in the early 2000s, when China’s leaders were more moderate than today’s leader, Xi Jinping. The idea was that Confucius Institutes would be established at foreign universities to provide Chinese language teachers and cultural programs. As China had emerged as a major international player, other countries were interested in equipping their citizens with Mandarin Chinese language skills and a knowledge of Chinese culture. Their goals and China’s goal of furthering a positive understanding of the Chinese culture and language dovetailed. The first institute opened in 2004, and some 500 of them eventually dotted the globe. More than 100 institutes opened in the United States, along with about 500 Confucian Classrooms to teach Chinese language and culture at K-12 schools. China sent hundreds of teachers to staff the institutes and classroom programs.

The name Confucius Institute was chosen to downplay politics when China was trying to establish its image as a moderate, responsible international player. Confucius, who is widely quoted and respected worldwide, was considered a benign, positive figure who represented this soft power goal.

The relationship between universities and the institutes worked as a subset of much more extensive academic and cultural exchanges between China and other countries. Despite some wariness about the institutes' agenda, they operated with little controversy at most universities.

However, the same can’t be said of broader Sino-foreign relations. China’s international image has tanked as Xi Jinping, who took office in 2012 and has consolidated his strongman status since, has pursued an aggressive international agenda and a repressive domestic one. Xi has gone nose to nose with the United States and other world and Asian powers over his belligerent stance that China should control the South China Sea, his crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong, his repression of minority peoples in the western Chinese province of Xinjiang, trade disputes, security breaches, the COVID-19 virus that originated in China, and the souring of predatory Chinese loan agreements and failed Chinese infrastructure projects abroad.

The upshot, according to a 2020 Pew survey, is that China is viewed negatively by majorities of 70-80 percent in the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, South Korea, Spain, France, Canada, Italy, and Japan. This is a sharp decline from the 50-60 percent positive opinions about China in Pew surveys when the first Confucius Institutes opened. Seventy-eight percent of those polled in 2020 had little or no confidence in Xi doing the right thing in world affairs. (However, more respondents had faith in Xi than in U.S. President Donald Trump, who had an 89 percent disapproval rating in the 2020 survey).

The result of China’s rocky international relations is that a number of countries have turned on the Confucius Institutes.

The U.S. Congress is denying Department of Defense funding to universities that host the institutes, citing concerns about possible espionage and intellectual theft at universities. The overwhelming majority of universities that have hosted the institutes have said no such concerns have surfaced on their campuses. However, Department of Defense spending on research at universities dwarfs the investment China has made in the institutes, and university officials say they can’t afford to lose the defense funding. More than half of the Confucius Institutes in the United States have closed since the peak of about 100.

Among U.S. universities who have closed their Confucius Institutes recently are the University of Buffalo, University of Utah, University of Alabama, Texas A&M, Tufts University, Colorado State University, University of Kentucky, University of New Hampshire, University of Southern Maine, Arizona State University, Indiana University, University of Idaho, University of South Florida, and University of Michigan. The College Board, which administers the SAT and AP tests, also has severed ties with the institutes.

Japanese authorities decided to conduct a review of that country’s 14 Confucius Institutes. Australia passed a law that would enable it to cancel contracts that colleges and localities sign with the institutes if they are deemed to run counter to national interests. Activists have protested outside the Chinese Embassy in Seoul, Korea, accusing the Chinese government of using the institutes to disseminate Chinese Communist Party propaganda. Sweden purged all of its Confucius Institutes amid deteriorating relations with China because of Chinese efforts to gain more influence in the Arctic.

Criticisms of the Confucius Institutes are that they lack reciprocity since democratic countries can’t have such institutes in China; that the institutes’ primary goal is to create positive feelings about China and then equate China with the Chinese Communist Party; and that Confucius Classrooms and institute teachers are trained to steer classroom discussions away from controversies such as Taiwan, Tibet, the 1989 pro-democracy Tiananmen protests, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and the South China Sea.

Chinese dissidents who have settled in the United States see the Confucius Institutes as an insult to their attempts to bring democracy and human rights to China. The Tufts University decision came after weeks of protests by students and pro-Tibetan independence activists against human rights abuses in Tibet and other parts of China. They believe the partnership of U.S. institutions with the Confucius Institutes implies support or naivete toward human rights abuses in China.

The main casualty of the closures is Chinese language programs. The United States is experiencing a critical shortage of China experts at the same time that it has an urgent interest in stabilizing U.S.-China relations so the two countries can work together constructively on common interests. Such work requires informed negotiators with realistic expectations about China and the ability to deal with complex issues involving China. Many, including the U.S. State Department, say that the United States needs to build better independent Chinese language programs as well as working with Taiwan, which is a democracy, to provide them. The problem with depending on Taiwan is that there are significant differences between Taiwan’s version of Mandarin Chinese and Chinese culture and the mainland’s. Not having teachers from China deprives students of exposure to the mainland perspective and language.

The closure of the institutes exacerbates a national foreign language problem caused by declines in U.S. government funding for higher education and foreign language studies.

Meanwhile, students in China are required to learn English from elementary school on and as a requirement for college admission. The result is that more Chinese, including front-line military troops, are learning English than the entire U.S. population.

University of Kentucky President Eli Capilouto in announcing the university’s closure of its Confucius Institute said the university had no choice because nine of its colleges receive tens of millions of dollars in research grants from the Department of Defense. The institute has made Chinese culture accessible to hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians and provided Chinese language and culture learning in K-12 schools, he said. “Now, we must find new ways and new paths to continue important relationships.”

The U.S. Department of Education has said that about 70 percent of U.S. educational institutions have not reported to the department funds they received from China for the institutes, which from 2012 to 2018 amounted to more than $113 million.

He expressed concern that the decision comes at a time of anti-Asian sentiment and pledged to stand by colleagues and students from Asian countries.

The closing of the Confucius Institutes is high on China’s list of grievances against the United States. Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Xie Feng told U.S. Deputy Secretary Wendy Sherman this month that the United States sees China as an imaginary enemy. He asked the United States to stop hindering the institutes.

Some universities have said the institutes were closed partly because of a decline in student interest in learning Mandarin as China has become less attractive to foreign business, COVID-19 has kept foreigners out of China, and Americans have looked askance at Xi’s policies.

The Confucius Institutes are jointly funded and managed U.S.-Chinese joint ventures, sometimes co-directed and sometimes directed by a foreign faculty director and a Chinese deputy director. The Chinese have supplied language teaching materials if requested and paid the salaries and international travel costs of Mandarin language teachers, study tours and research grants.

Some academics have argued that the institutes compromise academic freedom and institutional autonomy because they are a soft power instrument for the Chinese Communist Party and state. Studies in 2018 and 2019 found no interference by the institutes in mainstream Chinese studies curricula on U.S. campuses, and that the curriculum in most institutes was controlled by U.S. university personnel. Most of the institutes were limited in scope to teaching language and traditional culture. One study indicated that concerns that American students would be brainwashed by Chinese Communist propaganda were overblown because students surveyed have become more negative about China as the general public’s opinions about China have gone south.

China’s Ministry of Education reorganized the Confucius Institutes last year a nominally independent organization, a move that has not relieved suspicions about the propaganda role of the institutes because everything in China is subject to Chinese Communist Party leadership.

Confucius Institutes have continued to open in Chile, South Africa, Kenya and Greece, with plans to open more in some other countries.

Confucius' Influence

So what does Confucius have to do with all this? Confucius, or Kong Fuzi (551–479 BCE) was the paragon of Chinese sages and teachers. His teachings formed the basis of East Asian culture, society and education. He built up a reputation through his teaching and was appointed to government positions in a turbulent era. He taught some 3,000 students and also advised government officials.

Confucius championed family loyalty, ancestor veneration, as well as respect of elders by children and of husbands by wives. He considered family the basis for ideal government. He emphasized studying and internalizing classic texts and then relating them to current moral and political problems. He stressed self-cultivation, emulation of moral exemplars, and the attainment of skilled judgement. He became an ultimate model for the literati and public officials.

Confucian ethics are based on official ceremonies associated with sacrifice to ancestors and deities, social and political institutions, and daily etiquette.

He advocated doing the proper thing at the proper time, balancing between maintaining existing norms to perpetuate an ethical social order and violating them to accomplish ethical good.

His principle of yi, or righteousness, was based on treating others as one wants to be treated, enhancing the greater good, and doing the right things for the right reasons. His principle of ren, or benevolence, meant perfectly fulfilling one’s responsibilities toward others.

The best government, he said, ruled through rites, or li, and people’s natural morality, yi, rather than bribery or coercion. Ideal rulers would rise to power on the basis of their moral merits instead of lineage. These rulers would be devoted to the people and strive for personal perfection rather than imposing proper behavior with laws and rules.

Confucianism placed great value on rituals and etiquette, both on a national level and in daily life.

He believed that subordinates should give respect to superiors and advise them if they were taking a course of action that was wrong.

Confucius teachings became an elaborate set of rules and practices as his followers included men who became court officials. Confucianism coexisted with a more brutal Chinese train of thought, Legalism. After Qin Shi Huang, the emperor of China’s famous terracotta army, conquered all of China in 223 BCE, he abandoned Confucianism in favor of Legalism. He had many Confucian scholars killed and their books burned.

After his death, Confucianism rebounded, becoming the state ideology and required reading for civil service exams in 140 BCE. This continued off and on until the end of the 19th century. Confucianism also spread to Japan, Korea and Vietnam, partly through the establishment of Confucian academies in those countries that trained the literati to take positions in their governments. The academies, part of ancient Chinese soft power, were successful in spreading Chinese culture to those countries.

Confucianism in China today

After Confucius's death, his home town of Qufu became a place of devotion to him. It is a major tourist destination where crowds visit his grave and surrounding temples. The Qufu area has 405 village halls for teaching Confucianism. Nearly 10,000 villages in the surrounding Shandong province have such halls. In the city of Jining, a 72-meter-tall brass statue of Confucius, fireworks, tours and shows present the story of Confucius to tourists.

Spectacular memorial ceremonies are held in Qufu annually on Sept. 28, Confucius’ birthday. In the 20th century, this tradition was interrupted for several decades. Confucianism fell out of favor after the last imperial dynasty fell in 1912, as it was seen as outdated. The Communists rose to power in 1949 on an agenda of sweeping away the old. During the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, this included banning and burning Confucian texts. Confucius’s tomb in Qufu was blown up. Educators and parents were beaten and some murdered, destroying the Confucian social order based on respect for parents and teachers. Since the 1990s, Confucianism has experienced a revival as the Chinese Communist Party has coopted it to help provide a nationalistic moral base for Chinese society. The Confucian ceremonies in Qufu resumed as a way of venerating Chinese history and tradition. There also are Confucian temples in many other places as well as temples that combine veneration of the Buddha, the Daoist sage Laozi and Confucius.

Confucius' tomb in Qufu. It was blown up during the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, but later restored.

In Taiwan, Confucian memorial ceremonies were never interrupted. In South Korea, a grand memorial ceremony called Seokjeon Daeje is held twice a year, on Confucius's birthday and the anniversary of his death, at Confucian academies across the country.

Confucius is quoted constantly in academic and official settings and entertainment in China today. Xi’s government insists that China’s political system is based on Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and Marxism including Xi Jinping Thought.

However, Confucianism has always been a problem for China’s leaders because it was used not just to back up the state but to challenge it. Confucius said, “But if [rulers] are not good, and no one opposes them, may there not be expected from this one sentence the ruin of his country?”

Civil servants have frequently cited Confucian principles to criticize emperors. Most famous was Hai Rui, a Ming Dynasty official who pressed for land reform and was dismissed. His story was later used by reformist officials as a symbolic critique of Mao Zedong’s autocratic practices.

The pro-democracy activists of the 1989 Tiananmen protests were seen as getting inspiration from the West, but the movement also was deeply Confucian. Student leaders saw themselves as critics of corrupt leaders in the Confucian tradition. They staged Confucian rituals of petition to the authorities and gathered at Tiananmen Square as Chinese literati to present their views publicly to China’s modern rulers.

No modern Chinese leader wants to hear such criticism, and the government has made it clear that veneration of Confucianism must happen within the bounds of allegiance to Xi and the Communist Party. Xi and other Chinese officials, including the Chinese ambassador to the United States, Qin Gang, are fond of quoting Confucius on the way to pronouncing tough policies both domestically and to foreign leaders. Qin has suggested that the United States “should have a careful study of [Confucius’] works” to “first keep the heart upright, refine the soul, and then regulate the family well so as to contribute to good governance of the country and work to build a harmonious world.”

At the same time, Confucianism itself was not democratic. It upheld and advocated an authoritarian society that subjugated everyone in stifling hierarchies, with women in the most subordinate roles. Realistic policy makers in other countries recognize dealing with China is limited to working with an authoritarian government in areas in which their countries and China share common interests, while disagreeing over democracy and human rights.

Confucius is widely venerated in other areas of Asia. In Japan, a recent controversy arose over whether a 300-year-old Confucian temple in Okinawa was a religious venue and therefore not exempt from land rent. Okinawa’s mayor had exempted the temple on the grounds that it was a tourist attraction and place for learning. The Japanese Supreme Court did not say whether the temple was a religious venue, but ruled that the annual Confucius festival at the temple is a religious activity and the temple thus should not be exempt from land rent. Chinese weighed in on social media that the temple was being unfairly politicized. Many Japanese agreed, saying many Confucius temples in Japan could be affected by the judgement and it would be a shame if that led to the decline of Confucian cultural activities.

The concept of Confucian institutes that propagate Chinese values abroad is ancient in Asia. Confucian academies operated in Vietnam, Japan, and the two Koreas for centuries. The academies trained future bureaucrats to serve rulers and created a literati class that dominated cultural life. The academies revolved around reciting and analyzing classic Confucian texts and preparing for demanding civil service exams. The result was a literary and bureaucratic elite that ran the government. Getting a government post was a road to wealth and influence, so it was highly coveted. Public positions didn’t pay much, but they provided opportunity for influence peddling, bribe taking and skimming of government coffers. The academies were discontinued in favor of modern universities after the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912.

Some have suggested that China needs Confucianism to overcome its problem of a rapid falling birth rate. They have quoted his disciple Mencius as saying that population is the foundation of a country. The country’s former one-child policy and the rising cost of living have downsized Chinese expectations about family size, with dramatic declines in marriage and childbearing rates.

Confucianism emphasizes the importance of family, marriage and large families. It considers the dead and unborn part of civilization and that not having offspring is unfilial. Confucianism assumes that family is primarily responsible for the care of the young and the old. Under Xi, the Communist Party has brought back talk of family values and women’s importance as caretakers, messages that have not resonated with many Chinese women.

Confucianism saw individuals as part of a generational human chain, with the dead on one side and the unborn on the other.

There also is a moral void in China brought about by the Mao era’s attempt to strip China of its ancient social system, rapid urbanization, materialism, sexual liberation, and individualization. Many people have looked to religion - Buddhism, Daoism, Christianity, Islam, and Confucianism - for moral guidance. Some parents are exposing their children to Confucianism by buying Confucian tutoring services. U.S. investors have bid the value of these companies up, but their stocks dropped dramatically in price recently.

Some 18,000 Chinese students attend Confucian private schools in China that emphasize classic Confucian texts. Students at these schools read Confucian and Buddhist texts. Time reciting the classics takes away from them preparing for high school and college entrance exams, but some parents think such education will make them better people. The schools are an attempt to give their children a moral education they lacked.

The Chinese Ministry of Education has issued a directive to local education departments to pay close attention to private schools that use Confucian methods. At the same time, the government has increased the classics material on the college entrance exam.

Women participate in Confucian ceremonies in China today, but they would not have been allowed to do so historically. They held subordinate roles in traditional Confucian societies, and many modern Chinese women see a return to traditional Confucian values as unappealing.

In Qufu, descendants of the sage work at his temple and family mansion. One out of five Qufu residents identify as his descendents, many of whom are surnamed Kong. We knew people in China who claimed to be his descendants and had his surname.

Confucius's family has what is claimed to be the world’s longest recorded extant pedigree. The father-to-son family tree is in its 83rd generation. According to the Confucius Genealogy Compilation Committee, he has two million registered descendants, and an estimated three million total. Tens of thousands live outside of China. In the 14th century, a Kong descendant went to Korea, where some 34,000 descendants now live. One of the main lineages fled Qufu for Taiwan during the Chinese Civil War in the 1940s. Other branches converted to Islam after marrying Muslim women and today are among the Hui and Dongxiang minorities of China.

A 2013 DNA test on multiple branches that claimed descent from Confucius found that they shared the same Y chromosome, indicating that the descent was unbroken from father to son. Women descendants were included in the Confucius genealogy for the first time in 2009.

More photos of Qufu

Check out these related items

A Classical Chinese Garden

Lan Su Chinese Garden in Portland, Ore., was built by artisans from the garden city of Suzhou, China, to demonstrate the basic elements of Chinese gardens.

Ancient Silk Road Meets High Tech

The International Dunhuang Project digitizes old documents, caves and artifacts to enable global study of Central Asian history.

China’s Walled Cities

Only scattered remnants survive of the many walled cities that once defined the Chinese empire.

Chinese Moments Published

Chinese Moments, our photo book on China in the turbulent 1980s and 1990s, has been published as an ebook and paperback.

Inside a Chinese Painting

Take a quick break and enjoy spectacular scenery on a boat trip down the Li River near Guilin, China.

Traces of an Ancient Superpower

Traces of an ancient Chinese superpower remain far away in Japan, the eastern end of the Silk Road.