A Palace to Remember

Photos by Forrest Anderson

To be honest, I wasn't all that enthusiastic at first about visiting Heijō Palace in Nara, Japan. I got it that the site was one of the most historically significant in Asia, the former palace and eastern terminus of the Silk Road during the era when China's Tang dynasty spread the cultural splendor of its golden age to Japan and the rest of Asia. But what was there to see? The magnificent palace compound there had crumbled by the 12th century, leaving only rice fields in its wake.

I couldn't have been more wrong. The Heijō Palace historical site is one of the best I've been to, an absorbing historical tale told masterfully with modern state-of-the-art reconstruction, superb museum design and thoughtful attention to visitors. The result is a fascinating juxtaposition of ancient and modern that narrows the gap between Japan 's 8th century and the modern site. Given the paucity of artifacts uncovered at the site, the site does its job remarkably well.

Between 710-794, the Heijō Palace was one of the most important locations in Japanese and Asian history. It was the imperial residence and administrative center of Japan and the eastern terminus of the trade routes that stretched from the Middle East through China to Japan.

The sprawling palace compound in the north center of the Japanese capital of Heijō-kyō, now Nara, and indeed the entire city were designed using architectural and government models from Tang dynasty China. China under the Tang was prosperous and cosmopolitan. Cultural, political and religious exchanges spread Chinese culture throughout East Asia and into the Middle East and Europe as well as traveling the other way back to China. Heijō-kyō marked a high point in Chinese-Japanese relations and exchanges, when Chinese culture transformed Japanese customs, art, literature, religion and government in ways that have survived to the present.

A woman in a Tang dynasty costume stands in front of the reconstructed main hall at the palace.

The palace, like Chinese palace compounds, was a large walled area that contained ceremonial and administrative buildings including government ministries. The compound also included a separate walled residential compound called the Inner Palace where the emperor and his consorts lived and official and ceremonial buildings were located.

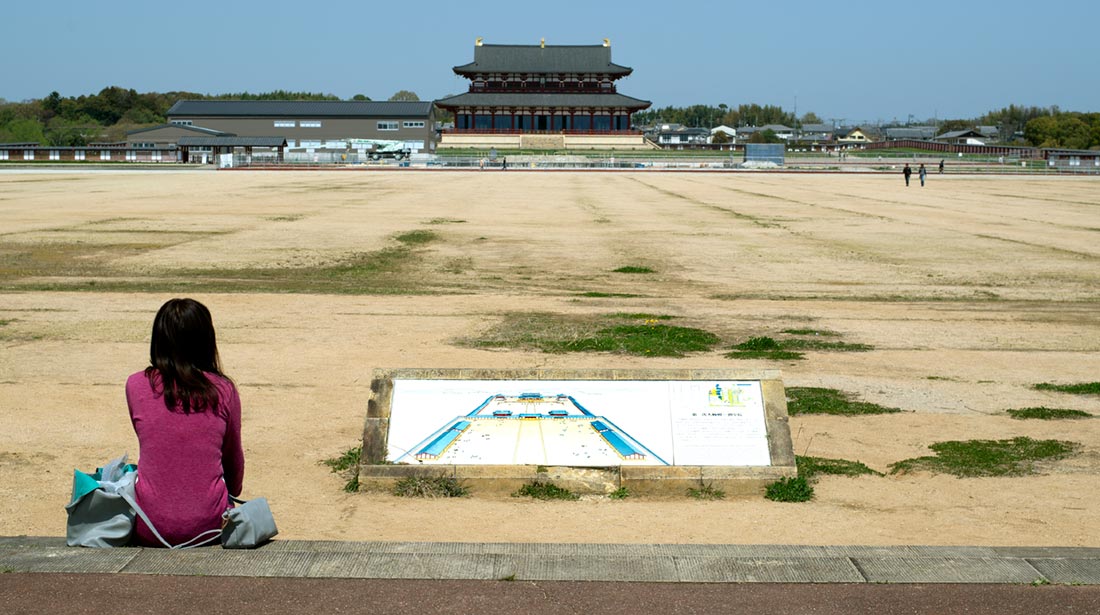

A tourist looks out over the current site of the palace, juxtaposed with a map of the original layout.

The palace’s role was to demonstrate the centralized government system called the Daijō-Kan or Great Council of State that the Japanese borrowed from China. The city and the imperial compound were based on the glittering Chinese capital Chang’an, which was located in present-day Xi’an, China. Chang’an was the largest and most impressive city of China’s long imperial era, and the model for not only the Japanese capital but capital cities in other Asian countries. Chang'an also later served as a partial model for future Chinese capitals including Beijing. As a result, Heijo Palace’s layout and the layout of the Forbidden City in Beijing share similarities.

Chang’an was a rectangle with a regular grid system of streets and protective shrines and temples placed at cardinal directions around the city. Heijō-kyō was similar. The Japanese imperial palace was located along a long axis extending from the city’s main north-south thoroughfare through the city center, similar to the layout of Chang’an and later Beijing. The thoroughfare ended at the Suzaku Gate, and palace buildings were to the north of the gate.

The Heijō compound was short-lived, as the capital was moved to Heian-kyo, now Kyoto, in 794. The palaces at Nara were either dismantled and moved to Kyoto or burned in fires. Almost no trace of the Heijō Palace remained. By the 12th century, the palace had vanished above ground. The site became farmland and stayed that way until the mid-20th century.

In China, Chang’an similarly disappeared after the decline of the Tang dynasty. During the 1950s, however, scholars began to study the site and literary sources from the period when the Heijo Palace existed. Archeological excavations began there in the 1970s. The remains of some of the buildings emerged. Fragments of the huge columns that once held up palace buildings, bases of columns and rubbish from the palace era enabled archeologists to determine where some structures and make some judgements about what went on at the site in the 700s. By the 2000s, the researchers knew enough to begin reconstructing the palace as a historical site.The first building on the site, Daigokuden, was reconstructed for the 130oth anniversary of the Heijō-kyō capital in 2010.

Suzaku Gate, the main gate of the palace compound, has been reconstructed. The large building seen through the gate is the main audience hall, on the main north-south axis of the compound.

The reconstructed Suzaku Gate and East Palace Garden opened to the public in 1998. The reconstruction was done by the Takenaka Corporation, a large Japanese company that has its roots in a family business started by a temple and shrine carpenter of the 1600s. Takenaka Corporation is known for having built some of the first Western-style buidings in Japan in the early 20th century.

The Suzaku Gate, the main entrance to the palace, got its name from a Chinese legendary bird which was believed to be a guardian of the south. The gate, in the Chinese tradition, was the palace’s southern and main entrance, and was the largest of 12 palace gates. It was along the main avenue and the second most important avenue extended east-west in front of it, again in Chinese style.

It is not known exactly how the original gate looked, but the architects of the reconstructed gate were able to make an educated guess because of literary sources and similar gates built in other locations in Asia.

The main buildings in the palace were the Daigokuden, where government affairs were conducted; the Chōdō-in, which was the main ceremonial hall; the Dairi or emperor’s residence, and offices for various government agencies. The only original building from the palace that survives is one that was moved to what is now the Toshodaiji Temple in Nara ans is now that temple’s lecture hall.

The Great Hall of State or Daigokuden (see the photo at the top of this page) was rebuilt in the same way. In ancient times, this building was the compound’s largest and most important. It was on the north of the compound facing south and is believed to have been a two-story Chinese-style building. There is no surviving information about the audience hall’s appearance.

The original building was moved from Heijo-kyo to Kuni-kyo, which was the capital city of Japan between 740 and 744. Although the city of Kuni-kyo was never finished, archaeological excavations there have revealed the bases of the pillars of the Daigokuden on which the relocated building was placed. As a result, the architects who designed the reconstruction were able to determine the size of the Daigokuden’s footprint. For the upper body of the building, architects studied other buildings that have survived from the same period such as the nearby Horyuji temple and a depiction of the Heian Palace audience hall in an an illustrated scroll of annual events and ceremonies called the Nenchu gyoji emaki.

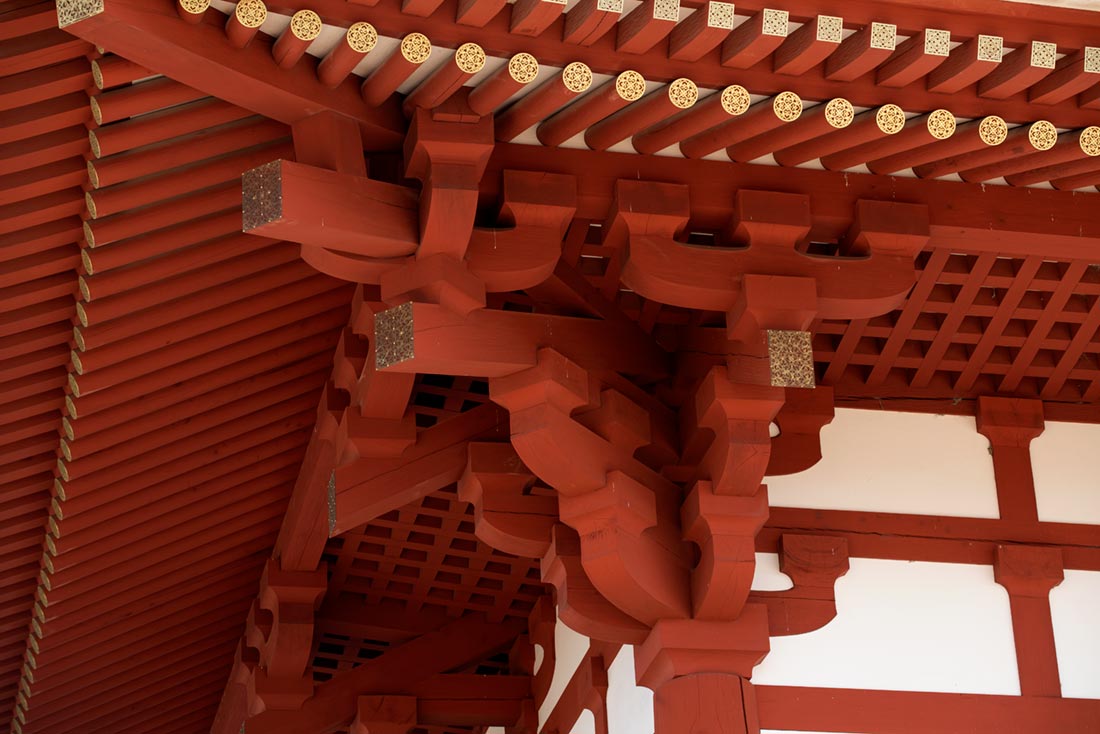

The reconstruction of the building took nine years from 2001 to 2010. It was constructed from Japanese cypress, with vermillion columns and beams in the traditional Chinese style for imperial buildings, white walls and ceramic tiles. The upper part of the hall’s interior was painted with Tiger, Horse and Ox signs of the Chinese zodiac and the ceiling has a floral pattern. The designs, based on Nara-period designs taken from 7th century treasures still extant in Japan, were painted by well-known artist Atsushi Uemura.

In the center of the audience hall was the emperor’s throne, which was called Takamikura and symbolized imperial power. The emperor sat there during his enthronement and during New Year’s Day ceremonies while noblemen lined up in the inner court south of the hall to pay respects, again a ritual borrowed from the Chinese imperial court. The original design of the Takamikura throne is unknown, so experts based it on the Japanese imperial throne of the Taisho Period, 1912-1926. However, they also consulted treasures from the Shosoin repository at Todai-ji Temple in Nara that which date from the period 701-760 to reconstruct decorative details on the throne.

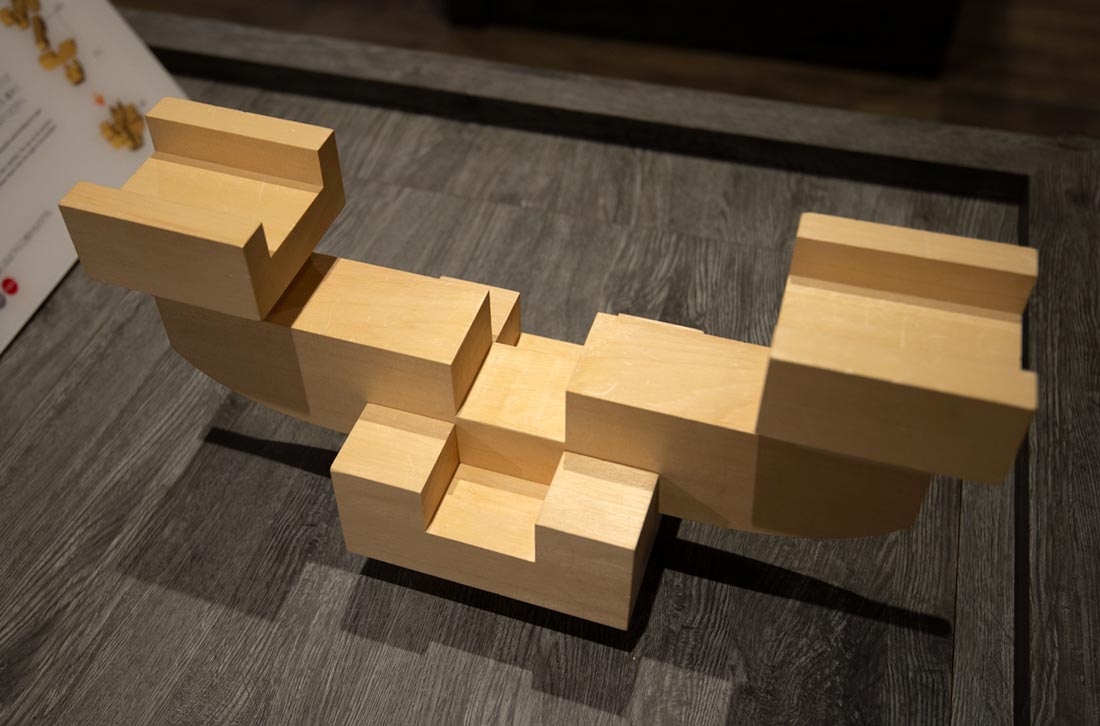

The audience hall was reconstructed using the complex Chinese roof bracketing system called the dougong. The system originated in China and was spread by artisans to Japan, Korea and other Asian nations. The museum on the site has comprehensive displays showing how the system worked, with sample dougong parts. A museum worker removed the protective glass cover on this display to allow us to take the following step-by-step photographs showing the way the bracket system fit together.

The historical site is superbly designed using simplified and modernized motifs from ancient architecture to blend with the historical aspects. This bench, below, was constructed using ordinary boards in a simpilified version of the dougong brackets.

This sample roof ornament on display inside the main audience hall shows the enormous scale of the golden roof ornaments on the hall's exterior.

Walls around ancient palaces in China and Japan were made of tamped earth, which became a core design motif in both countries. This display shows how the walls were constructed by erecting a wooden frame, adding earth and debris and tamping it down with heavy tools.

Ancient roof tiles found at the palace site. Below, replicas were created for use on the reconstructed main hall and front gate.

An area to the north of the Great Hall of State is believed to have been the site of the Office of Foods, which stocked foods used in the palace and provided the food for state banquets and rituals. Eating utensils and an inscribed wooden tablet were found in a garbage pit associated with this office.

Traces of the platform of another audience hall, dating from a time when the capital was re-established at Heijo after a brief period elsewhere, and of eastern state halls remain at the site. The imperial residence was north of the Latter Audience Hall. It was surrounded by a roofed corridor that was divided lengthwise by an earthen wall. The residence had a stone-paved area containing a large well that was rediscovered in 1973. It was lined with a cedar tube carved from a log.

The outlines of ancient buildings that were part of the palace compound, with the reconstructed main audience hall in the background.

East of the imperial residence is believed to be the site of the Office of the Imperial Household, which also was surrounded by an earth wall and had six buildings.

The remains of a large garden in the southeast corner of the palace were uncovered in 1967 and it was named East Palace garden because the neighboring area is believed to be the site of the East Palace. The garden had a pond with several buildings located around it. Banquets were held in a Jewelled Hall of the East Palace there. The garden originally was built in Chinese style and later modified to make it more Japanese. It was reconstructed in 1998.

The outline of ancient buildings also can be seen in patterns of bushes, poles and low walls indicating the former locations of palace structure.

One of the most interesting displays is a full sized replica of an 8th century diplomatic ship used by Japanese envoys to travel to China. Ships of this type once carried diplomats, students, monks and artisans to China and back to Japan as well as goods from along the Silk Road.

Exquisitely designed museums on the site exhibit the results of the archaeological excavations, including pieces of wooden columns, decorative tiles and exhibits that explain the wood construction methods used in ancient Japan and China and life in the palace. Artifacts, models, photographs and maps of the palace site are displayed. Among them are wooden tablets that were written on instead of paper at the time because paper was more expensive.

A wooden model showing the construction methods used to create the columned buildings at the site.

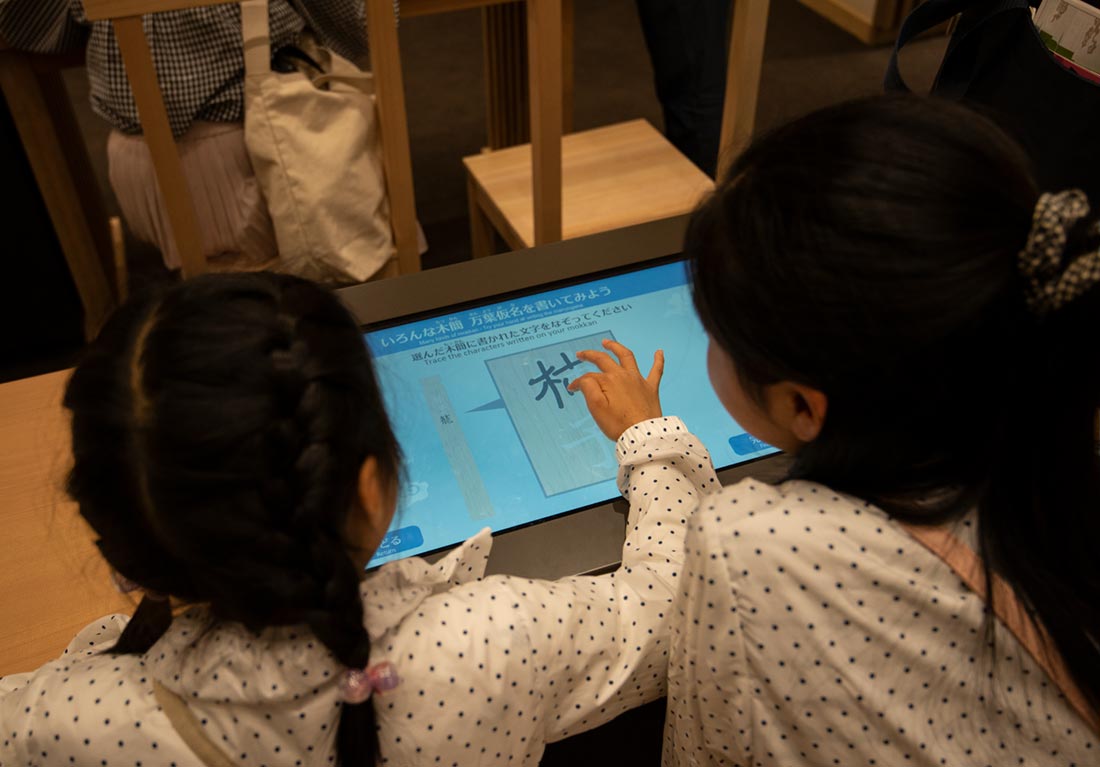

Children at the museum trace characters on a screen. The museum is a fascinating juxtaposition of the ancient and high tech. The effect is to collapse the centuries between the palace's hey day and the present to give museum goers a sense of what it was like in its heyday.

Check out these related items

Retreat by Design

What makes a retreat restful and soul restoring? A former imperial retreat in Kyoto, Japan, gets retreat design just right.

Battle of the Samurai

Osaka Castle marks the site of an epic samurai battle and one of the most important turning points in Japanese history.

The Summer Palace

The Summer Palace, the most famous and heartbreaking of China's glorious imperial gardens, highlights dilemmas in the nation’s past.

Treasure Room and Two Palaces

In the French palace at Fontainebleau is a treasure room of dazzling artifacts taken by the French army from a palace in Beijing.

What is the Louvre?

The former palace, the world's largest museum, music video and fashion show venue, and global brand has never been more cool.

The Tower of London

The Tower of London, enduring symbol of the British monarchy, combines royal pageantry with warfare, court intrigue and executions.