The Practical Power of Drawing

Drawings by Donna Rouviere Anderson; Photos by Forrest Anderson

I have drawn obsessively since I was three years old, when my older sister came home with her first-grade drawings and taught me how to draw. She moved on to other interests, while I stuck with drawing. A pencil line became my path through life.

My childhood dreams took form in my drawings. Owning a dress with a ruffly skirt, having a dog and a horse, living in a teepee or a treehouse, building and furnishing a log cabin, weaving a Mexican blanket all went into my plethora of drawings. As some of those dreams were realized, drawing became a bridge that made dreams possible.

In elementary school, I was a quiet kid who excelled in liberal arts and struggled in math and class participation, but I was the star of the class when it came time to draw and paint backdrops for the school Christmas pageant.

As a teenager, I was the designated creator of posters for church congregational events. My lab partner and I aced high school biology after we cut a deal on the first day of class for me to do all of our drawings and him to do the “urdy-gurdy-gopher-guts” dissecting that turned my stomach.

Drawing was the one activity that felt effortless, and whenever I could, I added drawings to school papers and projects.

Unfortunately, drawing also felt marginal. In my blue-collar world, people did something for a living and the eccentric ones drew or painted on the side. I gave up on high school art classes after tangling with an art teacher who told me that my realistic drawings of animals weren’t art and I should be making abstract paintings instead. I was a down-to-earth, practical kid, and my drawing was a practical exercise in reflecting and sorting out the real world. His views solidified the notion that pursuing art was impractical.

I majored in journalism in college, but took one art class every semester just for fun. Privately, I continued to draw my life as a continuing series of infographics that helped me understand and shape it. I drew houses that we built and lived in. I drew clothes that I sewed. I drew furniture that my husband and I built and jewelry that he created. I drew workflows and computer systems and made them reality.

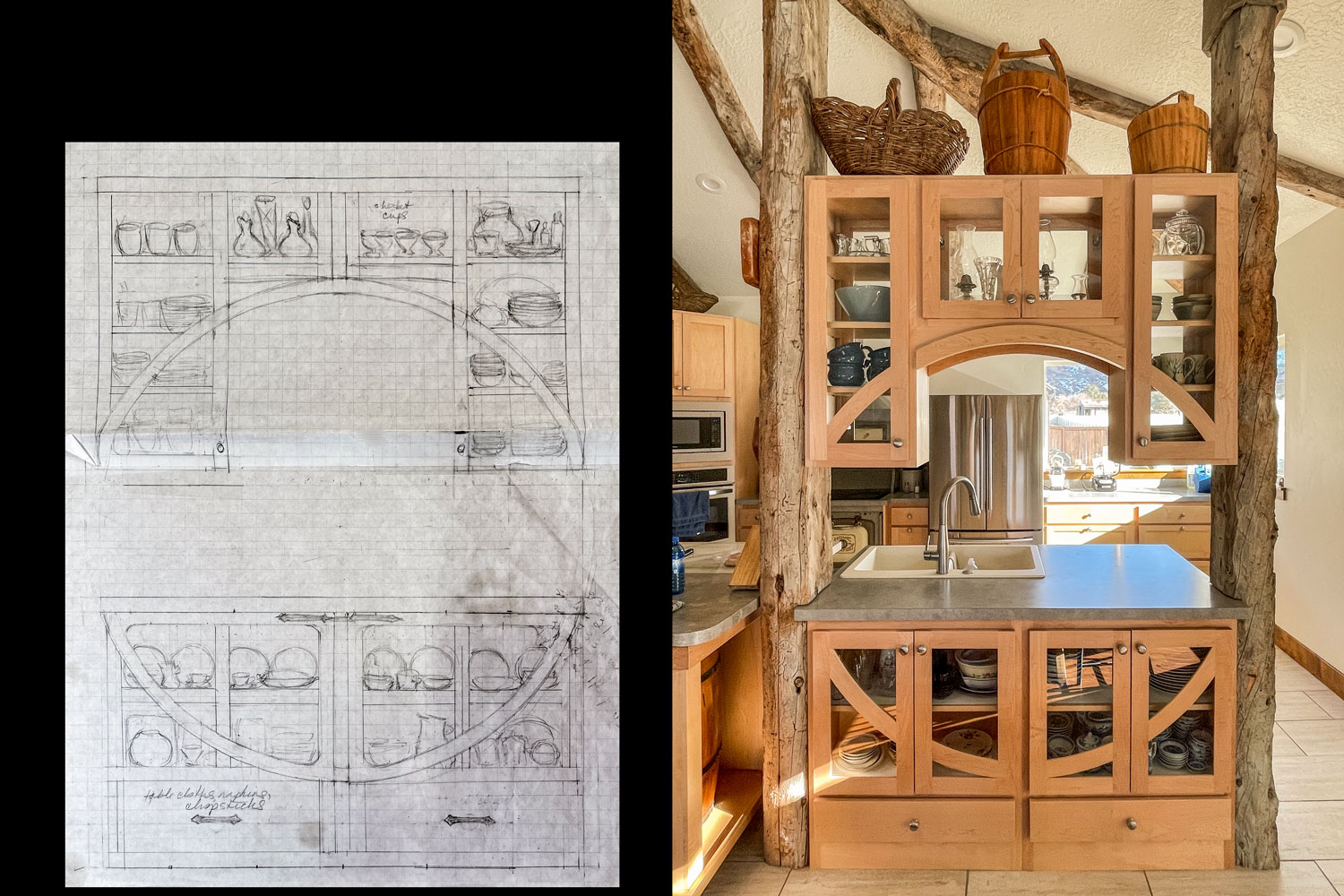

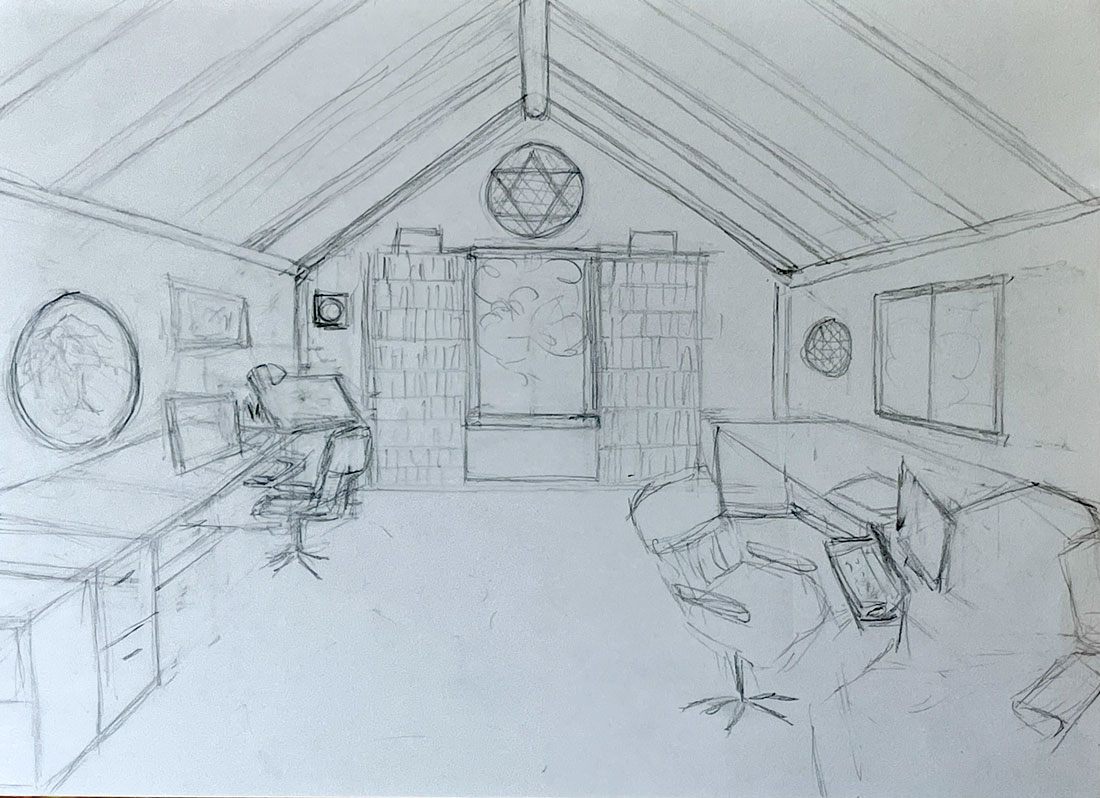

An early drawing for our studio and, below, the finished studio. The drawing became the jumping off point for the architect to create architectural plans for the building, which then were passed on to the builder and the sub-contractors. Once the basic studio was complete, we added the arch as shown below, which originally was part of the roof structure for a 19th century log cabin that belonged to our family. At each stage of construction, drawings were consulted and modified as the structure took shape.

I gradually shaped a career as a user experience designer, photo editor and writer in which drawing and design loom large. I now draw out complex processes, apps and websites and the layout for books before creating them in digital formats.

I no longer believe that drawing is marginal. This change in perspective began when our children were enrolled in a local elementary school in Beijing, China. Possibly because the Chinese language is made up of characters that are visual symbols for concepts, art took a more central place in the school’s curriculum than it is wont to do in American schools. Students at the school were taught to draw in a serious way as a cognitive skill akin to writing and math.

This helped me to define what I had always instinctively known but hadn’t defined – that drawing is a fundamental skill for analyzing and creating. It is one of the most efficient and sophisticated ways of thinking and communicating and the foundation for a wide range of careers and other life skills.

I mention my personal experience because it’s typical. I’m not the only one who has redefined the definition of drawing as the world has become more visual. Drawing has become a central activity in design, engineering, architecture, animation, fashion, film, theater, business communications, sciences, and social sciences such as anthropology and archaeology. Design departments in which employees draw constantly have become core to many businesses. Education, science, technology, mathematics, medicine and sports depend heavily on drawing to explore, explain and plan.

Drawing is fundamental to documenting and recording our world. As it transcends the many languages in the world with simple symbols, it has become its own language.

We find our way with GPS maps that began as a form of drawing. We locate bathrooms in an airport by looking for visual symbols that started as drawings. Interactive infographics that we call apps go with us everywhere on our phones, enabling us to know what the weather will be, check our finances, track our children, communicate, record exercise and assist us in myriad other tasks. Most of these began as a crude idea drawn with a pencil on paper before they were polished and translated into computer code.

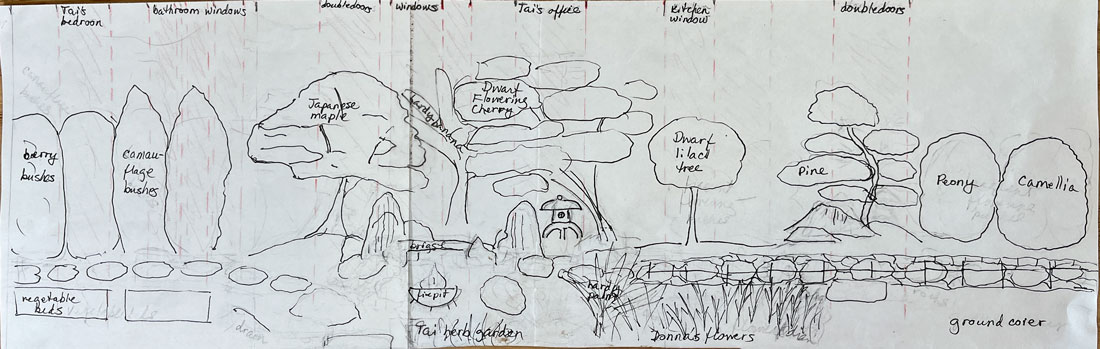

Different fields apply different drawn symbols to signify things in the real world. I appropriated common symbols and colors used by landscape artists to create these drawings of the landscaping in our back yard.

Drawings have a magical ability to become reality, often at a much reduced cost. Just as I finished the drawings for our back yard, the rock for the patio became available at either a much reduced price or free for the taking and small versions of the plants we wanted went on sale. Because of our drawing, we knew exactly what we needed. This is the rock patio in the yard shortly after we completed it. The drawings helped us to save money by buying small plants and placing them so that they would have room to grow eventually into the lush foliage that we envisioned.

As a means for communication and expression, drawing has become as important as the development of written and verbal skills. Forward-looking schools are embracing this approach.

As a society, all of us have become adept at drawing for informational purposes. When I asked my young niece Emma to describe her school, she immediately grabbed a piece of paper and created a sophisticated map of it, with her classrooms, lunchroom, playground and the activities that she carried out in each location at certain times. With a few sentences and marks, she helped me understand her entire school experience. Emma is already fluent in the visual language of drawing.

I recently asked a group of relatives ranging from ages 2 to 70 who were meeting on Zoom to draw their plans for the new year in one aspect of their lives. Without hesitation, they each created a schematic using symbols. It took them just five minutes.

The old mantra, “I can’t draw a straight line if my life depended on it,” is losing steam as drawing has morphed from something that only artists are confident doing to the simplest way to clarify and prototype our ideas. Its genius is that it is so widely accessible. All it takes is a pencil, paper and vision.

If our drawings are crude, so what? They still enable us to visualize and evaluate what’s floating around in our heads.

More people have let go of the notion that we have to craft polished, finished drawings in favor of an iterative approach that moves quickly and intuitively over paper to express and explain what we are thinking at this moment. Drawing is less about performance and more about process – a way of observing the world and learning as we go.

We have no compunctions about chucking a drawing and starting in anew. This perspective is relatively recent because drawing was for hundreds of years connected to the high cost of paper, which caused artists to think carefully before starting to draw. The genius of drawing in the modern world is that almost everyone has access to paper and a pencil. This plus the ability to draw on a whiteboard or tablet screen has freed us from this artists’ block.

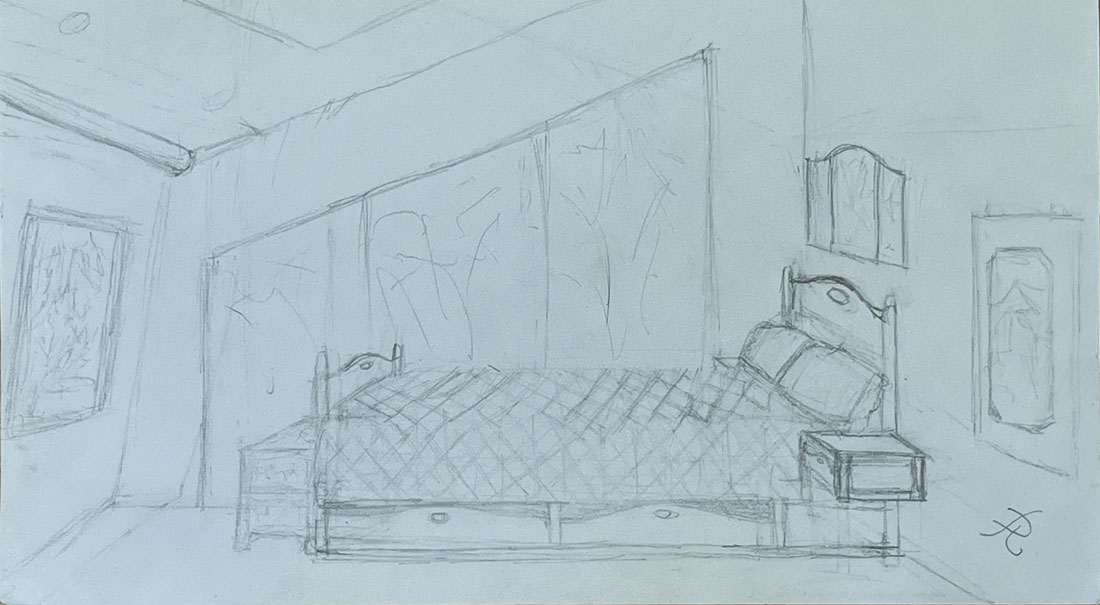

This is an early drawing of our bedroom that I created. It eventually iterated into the final version below. Drawing as part of an iterative process is crucial to modern design of all kinds.

So what is going on in our heads when we draw?

The mental process of drawing as an expression of internal thoughts has been a formal research subject for the past half-century. Here are some things researchers have discovered:

The results of a drawing are often different than the initial concept that the creator had in mind. The point of drawing doesn’t seem to be for the initial concept and final drawing to match. Instead, drawing is a conversation between the creator and the idea which brings initially unintended features into a drawing. The result is that the final drawing is functional with regard to the initial requirements, but something beyond the initial idea has happened in the drawing process.

The process of drawing is a complex system of human adaptation. We make judgements as we create a drawing about what needs to be included in it to meet a need. For example, a stranger asks us for directions to a location, and we draw a map marked with significant directions and landmarks that the recipient uses to guide them to their destination. Our map doesn’t reproduce the topography faithfully or even the distance to scale. We instead draw in a common visual language of symbols such as parallel lines to represent roads, arrows to denote directions left or right, and boxes with labels to represent landmarks. Drawing a map is part of a complex communication system that transcends spoken languages. I have had people whose language I didn’t speak draw maps that got me to my destination in Europe and Japan. Even though we couldn’t speak each other’s language, we communicated in a more universal visual language.

Culture can be important to drawing, especially in fields such as mathematics, surgery and engineering in which colleagues communicate concepts through drawing symbols. If you’ve ever had a doctor draw symbols on you before taking you into surgery, you know how this can work.

Drawing is fluid and adaptive. It enables us to reference the past, but also innovate for modern cultural relevance. The happy face symbol, which was first drawn in the 1960s, has gone through thousands of iterations and products, and is drawn by teachers on school papers and by pediatricians giving children a clean bill of health. In recent years, it has developed into one of the most powerful modern visual languages with a plethora of happy, sad, angry, etc. emoticons that we send out in texts. Drawing sets us on paths of evolving and developing as we work out concepts visually.

Drawing interacts with our cultural, mental, biological and physical situations and our memories to make new things that are beyond the sum of their parts and the creator’s original expectation. It is these relationships that make drawing so complex and powerful. Drawing gives us the ability to understand thoughts in ways that can’t be expressed in any spoken language.

Drawing creates meaningful interactions between the creator, the subject and the audience. In many cases, these interactions can be life-saving or life-transforming. Traffic signs are a common example.

Drawing is an iterative process that is the result of both internal and external feedback, a productive way to move ideas forward. It is an on-going part of the process of creating something in almost any media, whether it is a rocket, a piece of furniture, a piece of clothing or a building. The process of drawing continues along with fabrication as a prototype is modified to achieve a successful result. Drawing defies attempts to create a set of steps because it is not a closed system. It interacts with the world around it.

Drawing also interacts with the growing knowledge of the creator as they work out a problem. The act of drawing creates knowledge. Architects, for example, have knowledge about how materials and types of structures that work for certain functions and in spatial arrangements. They understand the correct standards for making decisions. Drawing allows them to bring this knowledge together to create and modify building plans that are more than the sum of their subject matter knowledge.

Those who draw tend to be curious and experimental, so they are constantly expanding the possibilities of paper and pencils and redefining the notion of what drawing is.

Drawing captures moments. A mark can represent a movement or gesture moment in time that can be transmitted across generations, although the drawing’s meaning can change in the context of a later generation. Thus drawing captures not just scenes but motion. This ability comes into play in a wide variety of fields such as animation, engineering and cartography.

When students learn to implement basic visual organizational techniques and principles, it helps them organize information in a variety of fields. Anyone can learn these principles, which include communication, perspective, proportions, anatomy of people and objects, light, color, gestures, styles and edges.

Drawing enables us to show three-dimensional objects in perspective on two-dimensional surfaces and to show relations between the sizes of different objects. We can show how human and animal bodies, plants, vehicles, buildings and machinery function. Drawing is the basis of understanding how things work and interact with each other.

Drawing includes composition, or the placement of visual elements on a page to convey particular meanings. Even a simple drawing uses light (the white page) and darkness (the pencil lead) to define edges, reveal volume and set the mood. Drawing can include color to add emotional impact and meaning.

The style of a drawing can convey the historical, ethnic or symbolic nature of a subject. .

Drawings can communicate large and complex amounts of data, meaning and stories quickly.

A drawing can immerse an audience in a new environment.

But why draw if you don’t have a job that requires it? Research indicates that drawing helps train intelligence, memory, and emotional intelligence. Done regularly, it improves concentration, focus, awareness and connection with our inner thoughts and others. It helps us explore our emotions and ideas and build confidence in our creativity. It is part of creativity and experimentation as a way of life.

Researchers believe that the fear of drawing, like fear of speaking, is universal even among creative professionals. However, professionals keep drawing because they have learned to see drawing not as a chasm they could drop into but as a bridge connecting their ideas with reality.

Most children draw prolifically and enthusiastically when they are young. Between the ages of two and four, they scribble. They start to use shapes and symbols to explore relationships and their environment when they are between four and seven. Between seven and nine, they develop a consistent way to draw objects, people and environments to show knowledge. They add details and realistic features to drawings between ages nine and twelve. Then they hit adolescence.

Between the ages of twelve and fourteen, they start to focus on whether their drawings look good and their parents and peers like them. As a result, many adolescents become displeased with their drawings and drop out of drawing. This happens partly because they don’t get encouragement and drawing instruction, so their skill level plateaus and their interest and confidence dissipate.

Unfortunately, many teachers, especially on the high school level, are not trained in how to use drawing as a tool for learning. Drawing is confined to the art department, when in fact it should play a role in many subjects and later in the workplace. It is useful for visual mapping, organizing and presenting information and communicating across language barriers.

Those who persist in drawing in their teenage years must make a conscious decision to do so. Many artists have stopped drawing during this phase and gone through a long period when they didn’t draw before resuming drawing as a private form of self-expression. At this point, they focus on using drawing to work through problems rather than on what other people think of their work.

Many people say they would like to draw but don’t have time. I didn’t begin to draw daily until I realized I needed a few minutes daily to think through things. I often used that time to draw solutions to problems and found that it was a powerful tool for saving time and resources in the rest of my life. When I work through a solution on paper, it almost always become simpler and doable. Drawing helps me sort myself out from the many possible selfs I could be in our complex society. It helps me be honest and clarify my goals. It forces me to slow down and focus on the most important things.

Drawing and design help me connect with people. Like many people, I dislike personally being the center of attention and prefer sharing products that I create. It also helps me give to a larger number of people than I could otherwise reach.

Studies indicate that when people are anxious and overwhelmed, drawing can enable the pressure to lift. Many people say they feel happier, more confident and like they have a greater sense of purpose when they draw. Some report that they can express their thoughts better to others after drawing. Drawing helps them concentrate on the present moment rather than dwelling on the past or stressing about the future. It reminds them that they can control their thoughts and feelings. It helps them feel more secure about who they are, but also to move past themselves. Because everyone has a different style of drawing, it helps them express themselves in unique ways.

Drawing doesn’t have to be solitary. It can be a fun skill to do with other people.

Drawing dates back long before the history of paper. Drawings have been found on cave walls, tomb walls, walls of houses, ceramic pots. Drawing seems to be wired into the way our brains express themselves. Researchers say humans actually appear to be hard-wired for drawing, with our fine hand motor skills.

Studies have indicated that drawing activates both the right and left brain hemispheres. It is used in therapy for Alzheimer and dementia patients, and some studies indicate a 70 percent improvement in patients’ memories from drawing. It helps make memories stronger and more accessible.

Drawing also is used as a therapy for patients with depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder because it releases positive serotonin, endorphins, dopamine and other chemicals in the brain.

Drawing trains people to be more observant, see details and remember facts better as well as to perceive the world more accurately. It helps shy people or people with verbal disabilities to communicate better.

Many adults abandon drawing because it has been given too narrow a definition as a professional skill or innate talent instead of a broad life skill, but the ability to draw is not innate. It can be taught and developed. It is a learning tool for seeing and understanding the world that no one has a monopoly on. The dense network of nerve endings in our hands are made for subtle activities such as drawing, and drawing develops hand-eye coordination, hones analytical skills and teaches people to conceptualize ideas.

Many people who don’t see themselves as having artistic talent scribble doodles in the margins of notes. It turns out that doodling during a boring lecture helps students pay attention and remember. In one study, people who doodled remembered 29 percent more than those who just listened to the reading of a list of names. Participants in studies who drew the concept of items in a list recalled twice as many of the words as those who hand copied the list. In another study, people were asked to listen to a dull voicemail message. Half of the participants were instructed to doodle while listening; the other half were not. Those who doodled remembered a significant amount more of what they heard than those who didn’t.

Drawing is particularly good for creating symbols. Coaches teach the rules and strategies of games by drawing symbols and teachers use it to teach geological layers, cell functions and many other concepts.

Reading, seeing, and drawing are different ways to interact with information. It has long been understood that combining illustrations with words enhances understanding, but worksheets on which children read, write and draw are now popular ways to enhance both reading comprehension and writing. Researchers have found that when undergraduates drew science concepts, their recall was nearly twice as good as when they wrote down definitions supplied by the lecturer.

When children draw before writing, their writing is generally richer, longer, more sophisticated and more varied in vocabulary.

Studies indicate that drawing is superior to listening, reading or writing alone because it forces people to process information in multiple ways. Drawing forces students to reconstruct what they are learning in a way that makes sense to them.

The strength of a memory depends largely on how many connections are made between it and other memories. We forget isolated pieces of information quickly because our brain prunes unused knowledge. Memories that have more connections resist being forgotten. The act of drawing layers a visual memory with the memory of our hand drawing it and its meaning, so we learn it three times.

Teachers and parents can help children learn better by having them draw posters to put up in classrooms or their bedrooms rather than buying them; having children use one side of a notebook for written notes and the other for diagrams, charts and drawings; and asking them to present subjects, stories or solutions to problems in the form of drawings.

Teaching drawing as a cognitive skill holds promise in working with spatially gifted students, who have the potential to become engineers, architects and product designers if their skills are recognized and nurtured. Such students often struggle with multiple-choice tests and essays and should be allowed to do drawings or three-dimensional projects to demonstrate mastery of subjects. At least 4 to 6 percent of U.S. students are exceptionally gifted in spatial reasoning. Research shows that when such talents are identified and trained, their school performance improves consistently. Drawing is an inexpensive way to do that.

Check out these related items

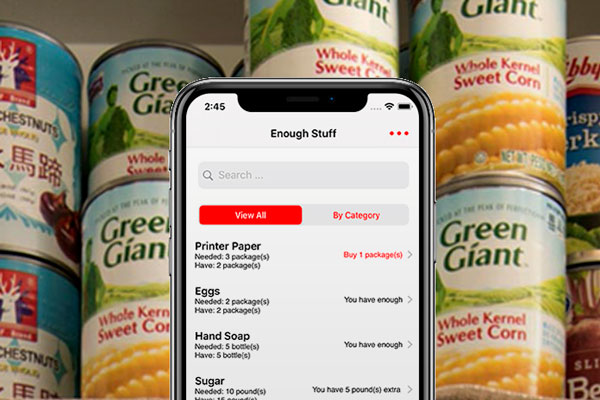

Enough Stuff App

The Enough Stuff inventory app for iOS helps you keep track of how much you have of items so you don't buy more of them than you need.

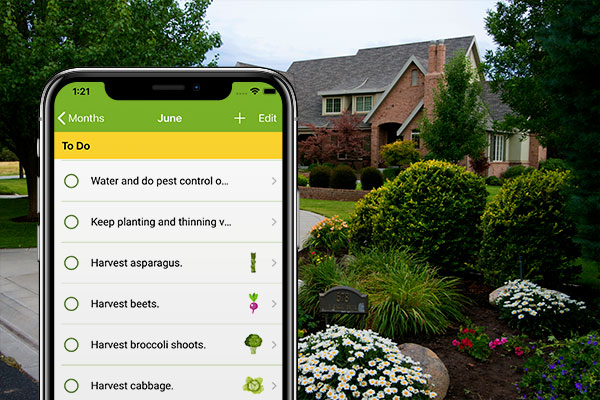

Green Thumbometer App

The all-in-one iOS app that's a gardening calendar, gardening journal, gardening to-do list and source of gardening information.

Home Gnome App

The iOS app that helps you keep track of what tasks you need to do and when to do them to maintain your home well all year long.

Making the Invisible Visible

The field of data-based infographics is helping the world see, understand and respond to the invisible threat of the pandemic.

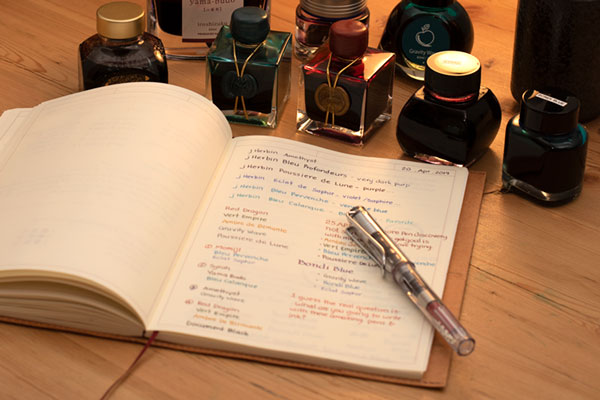

Hand Typing

Simple, legible, careful handwriting on beautiful paper seems old-fashioned in a digital era, but an iOS app developer counts it as one of his most useful tools.

How Crafts Help Us Cope

Crafts are booming as people shelter at home during the pandemic. We explore why, as well as ways to learn a new craft without stressing out.

Building an Arch and Cabinets

To carve space for our office out of a larger living space, we built an arch and cabinets out of old reclaimed beams.

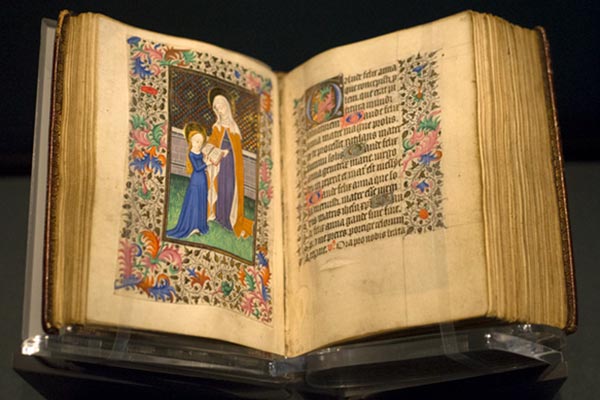

Illuminated Manuscripts

Illuminated medieval manuscripts preserved culture and religious beliefs and set a foundation for book design and art styles.

Let’s Get to Work - From Home

Remote work is one of the best ways to limit the coronavirus and keep the economy going. Here's a guide to how to work from home.